“We are in class to learn skills, not to experiment and play. We are not paying to sit around and teach ourselves.”

“We don’t understand where our money is going.”

“We are outraged.”

Last fall, a small group of Parsons fashion BFA students created a secret group on Facebook to air their grievances about our new administration’s controversial new curriculum. “Constructive complaining,” they called it. A way for students to work together to effect change. The group has now grown to 177 members, but unfortunately, little has changed.

According to a recent article in The New School Free Press, “Parsons administrators contend that those complaining are in a minority.” Besides, they say, the changes to the curriculum are necessary. Our dean, Simon Collins, was quoted as saying, “Every year it should change… we’re about designing better solutions.”

Here’s an example of the “solutions” he’s talking about:

“Under the old curriculum,” as noted in the Free Press, “students learned how to construct clothing — via sewing, pattern making and draping — in some classes, while learning how to design in other classes. Taken together, the courses were intended to give students the necessary skills to construct their own designs.”

Under the new curriculum, students who haven’t already taught themselves to sew must take workshops for no credit and on their own time, or “get help from private tutors at their cost, or learn on their own with the guidance of YouTube videos.” Sophomore Andree Ciccarelli told the Free Press, “We have had to teach ourselves much of the subject matter.” Sophomore Andrew Shields succinctly noted, “It is ridiculous.”

He’s right. It is ridiculous. According to Forbes, Parsons is the third most expensive school in the nation. And the only thing more ridiculous than a bunch of middle-aged instructors like myself teaching today’s 19-year-olds about the importance of play is the administration’s belief that parents will continue to pay good money for this dubious service. Especially in this job market.

Whether it’s Tom Ford at Gucci or Marc Jacobs at Louis Vuitton, Parsons’ fashion alumni have long defined not just American fashion, but fashion throughout the world. Donna Karan, Anna Sui, Jack and Lazaro of Proenza Schouler, Alexander Wang, Jason Wu — the list goes on and on. The single most prevalent factor among winners of the CFDA Best New Designer of the Year award is the fact that they studied at Parsons. More than a third of the winners have passed through our halls. FIT is a very distant second, with less than one-tenth. As sophomore Juliana Gibbons asked, “If you have one of the top programs in the country, why on earth would you change it?”

“Parsons is supposedly one of the top three (schools) in the world for fashion design… and we didn’t get that way from using YouTube.”

Many students and faculty agree that the new curriculum is similar to the British pedagogical model exemplified by Central Saint Martin’s in London. Yet Simon Collins, our dean (of Bournemouth and Poole College of Art and Design), will tell you that the new curriculum was definitely not influenced by this British approach. True, Yvonne Watson, our director of academic affairs (Nottingham Trent University), and Kyle Farmer, our former associate director of the BFA program (Royal College of Art), were both instrumental in designing the sophomore and junior curricula. Nevertheless, Tim Marshall, our provost, concurs: the new curriculum is absolutely not imitative of Central St. Martin’s, his previous employer.

Why do they deny what seems to be the very obvious influence of this British model? An article from The Guardian in 2008 provides an answer: Some years ago British fashion students realized that their schools were not teaching them the basic skills they need to work in the fashion industry. This is dismaying for those students who leave British fashion schools “saddled with thousands of dollars in debt and no valuable skills.” It also has repercussions for the U.K.’s fashion industry. Linda Florance, chief executive of Skillfast, the sector skills council for fashion and textiles, told The Guardian, the industry “requires highly skilled people with a broad range of practical talents, but the education and training system just isn’t delivering enough of them, and employers are increasingly concerned.”

This is not to disparage the U.K. Many industries in the U.S. share the same concerns. A recent series of articles in The New York Times noted that, by the time they graduate, U.S. law students have spent “three years and as much as $150,000 for a legal degree. What they did not get, for all that time and money, was much practical training.” As Jeffrey W. Carr, the general counsel of FMC Technologies, told The Times, “The fundamental issue is that law schools are producing people who are not capable of being counselors.”

A 2006 survey of business leaders found that “among those new hires with a recent college degree, employers say only 24 percent have an ‘excellent’ grasp of basic knowledge and applied skills,” according to Corporate Voices, a leading national business membership organization. “Ninety-seven percent of the business leaders surveyed agree that workforce readiness is a critical business imperative. They are deeply concerned about their future workforce and the cost of providing training to a generation of ill-prepared workers.”

“I strongly feel that a general understanding of construction of garments will become my benefit whether or not its Parsons’ priority. I am very determined and willing to pay for private lessons.”

The question arises: If these “YouTube solutions” do not benefit our students, and do not benefit our industry, then whom do they benefit?

The New York Times recently asked, “Have colleges, in their efforts to keep graduation rates high and students happy, dumbed down their curriculums? If they have, who is to blame?” Leon Botstein, president of Bard College, notes that colleges are currently ranked “not by criteria of academic rigor but by graduation rates, encouraging institutions to hold on to students at all cost lest there be the specter of attrition.” George Leef, of the John William Pope Center for Higher Education Policy, also blames the need to keep students enrolled. “(M)any schools have acquiesced in or even encouraged the faculty to lower academic standards… Intellectually vapid courses and programs that will attract customers have proliferated.”

Proliferated, indeed. Parsons fashion program has grown exponentially since I started teaching here 11 years ago. While this expansion and our new focus on student retention may be good for The New School’s bottom line, it isn’t doing anyone else any favors. Students who can’t handle our new playtime curriculum are unlikely to ever build a career in an industry that stubbornly insists on technical proficiency. The New School is profiting from the gullibility of these students and their parents. As in the British system, they will leave “saddled with thousands of dollars in debt and no valuable skills.”

Carla Westcott is a Parsons colleague who has owned an eveningwear and ready-to-wear business for 15 years. “I am a business person,” she says. “I have no use for employees who do not possess a complete knowledge of draping and pattern making skills. My design assistant is a Parsons BFA graduate who possesses these skills. If she did not, I would not have hired her.”

Most Parsons fashion part-time professors (i.e., most of the faculty) currently work in the industry. We share Carla’s perspective and her concerns. Last fall, we came together and voted “no confidence” in our administration and their direction for our program, 42 – 8, with one abstention. “Our curriculum has been stripped down to ‘play, explore and experiment,’ without the basic skills students will need to get a job in a very competitive American and global marketplace and volatile economic environment,” we said. But again, unfortunately, little has changed.

It’s one thing for the administration to dismiss the concerns of 5 out of 6 faculty members. We are, after all, employees. But the concerns of the students are another matter. If they’re not happy, Parsons is out of business. For the students, this is it. This is their education. They only get to have this experience once, and it’s a shame — it is truly shameful — that so many of them find it so disappointing.

“Students feel that we are not being heard. We feel like giving up, and that no matter what we do or say, things will not change.”

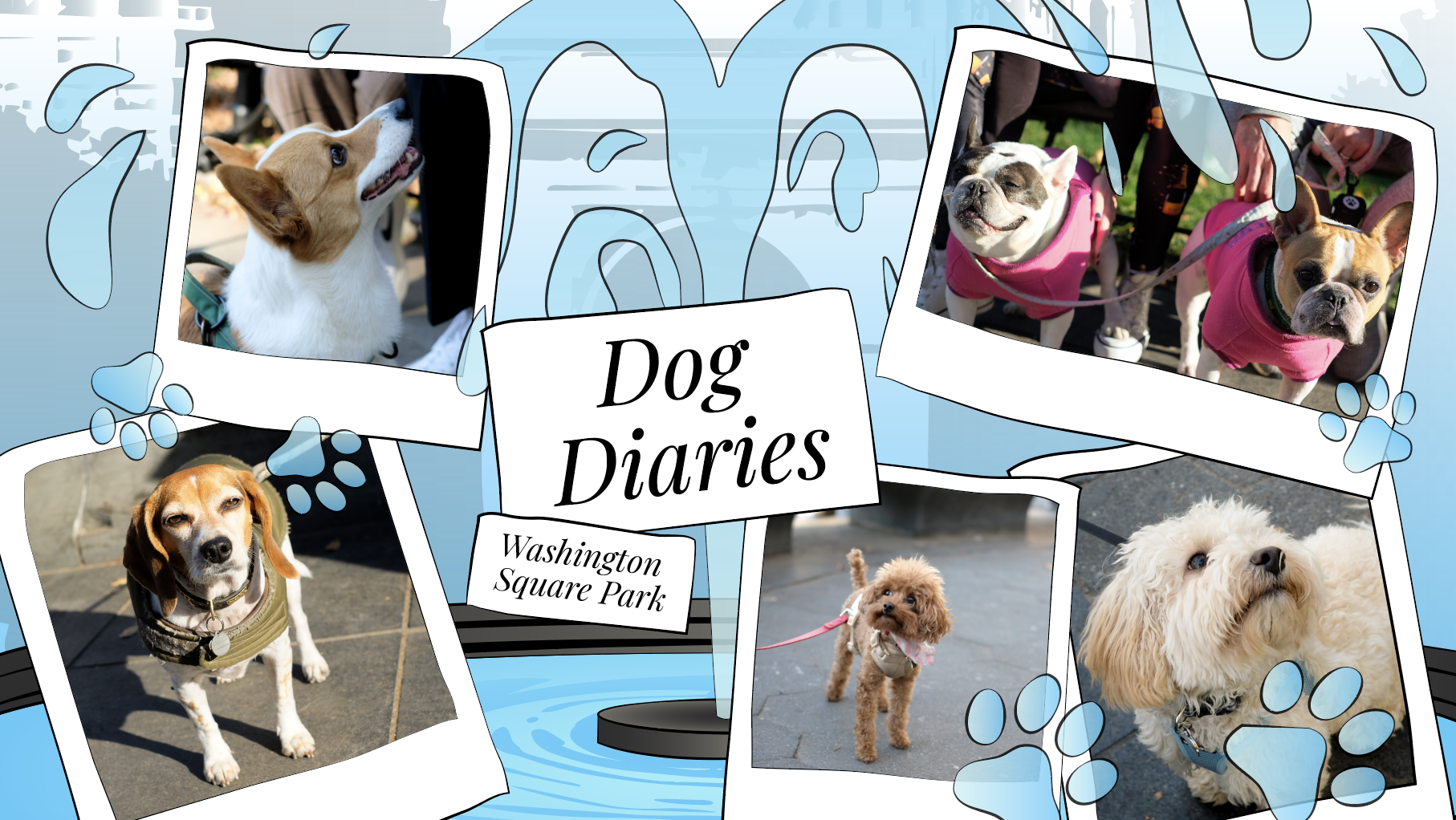

Many of today’s fashion students grew to know and love and aspire to attend Parsons because of “Project Runway” and its charming mentor, our former chair of fashion design, Tim Gunn. Tim trained as a sculptor, and one might imagine that if anyone would be inclined to extol play over practice, it would be a fine artist. But Tim has always shown an abiding respect for the rigors of design and the challenges of building a career, even in an industry as seemingly frivolous as fashion.

There’s a reason he famously exhorts his designers not to play, but to “make it work.” It’s a lesson that seems to have been lost on his successors.

Michael Johnson is an illustrator, a graphic artist, and part-time faculty in Parsons’ Fashion Design BFA program.

Leave a Reply