The curious case of Bob Kerrey’s compensation

In the fall of 2009, shortly after he assumed the chairmanship of The New School’s board of trustees, Michael J. Johnston had a conversation with his longtime friend, Bob Kerrey, about Kerrey’s future as president of the university. With Kerrey’s contract approaching its end and financing for his ambitious University Center construction project still needing to be finalized, the board wanted to know if they could count on the president to stay.

“He said he wasn’t sure [whether he would stay], but he thought so,” Johnston recalled in a June interview with the Free Press. But later that fall, after speaking to him once more, Johnston found that Kerrey was having doubts about his position at The New School. “He said, ‘No, I’m not going to stay.’ He was going to serve out his contract and start looking for something new.”

“Something new” could very well have been the top job at the Motion Picture Association, who were vetting Kerrey at the time to lead their operation in Washington, D.C. For Johnston, the possibility of Kerrey leaving the university for the MPAA job or another opportunity — before the University Center financing was finalized and before the trustees had the means of finding Kerrey’s replacement — was a risk the board wasn’t willing to take.

“I talked to several of the trustees, and we all agreed that we didn’t want to run the risk of losing Bob to an outside job of some kind,” Johnston said. “We had a lot we wanted to do to get ready to search for a new president.”

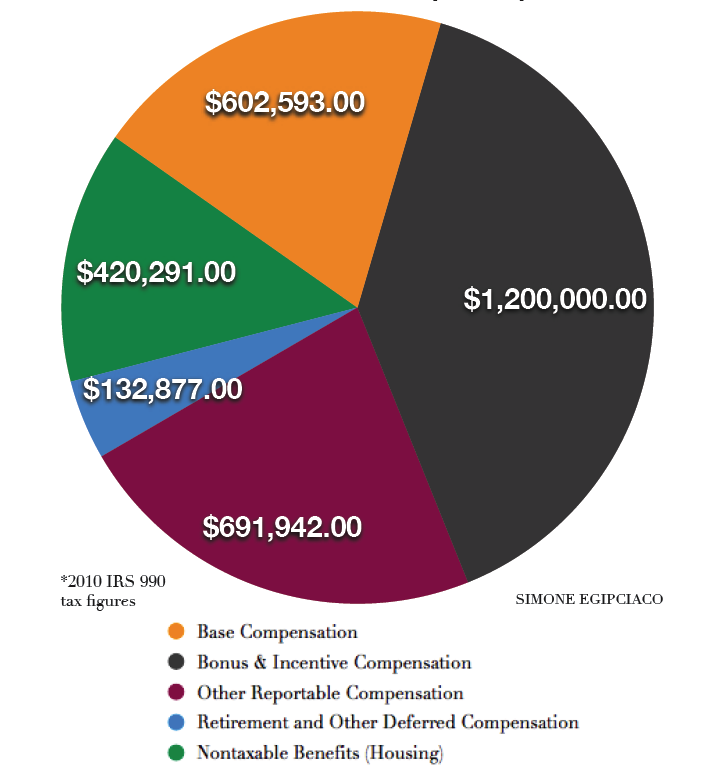

So the board, with the counsel of law firm Proskauer Rose and the accountancy firm PriceWaterhouseCoopers, decided to negotiate the terms of what would presumably be Kerrey’s final agreement with The New School. The contract, once signed and sealed, would give Kerrey a retention bonus amounting to $1.2 million in 2010, his final year as president of the university. It would ensure that Kerrey stayed at The New School through the end of his contract, remained at the university to finalize the financial terms of the 65 Fifth Ave. project, and assisted the board of trustees in its search for a new president.

The bonus also meant that Kerrey’s total 2010 compensation from The New School would eclipse $3 million, making him one of the highest-paid private university presidents in the country. According to The Chronicle of Higher Education, only two private university presidents in the United States earned over $3 million in 2009: Constantine N. Papadakis of Drexel University and William R. Brody of Johns Hopkins University.

Kerrey’s new contract also established the terms of his relationship with The New School after his time as president would come to an end. He would be granted the position of president emeritus, eligible to earn between $400,000 and $600,000 a year from the university through 2016 — “close to, if not the full [base] salary” he earned as president of The New School, according to Johnston.

“I think that despite the challenges he faced at The New School, there’s no question that Bob Kerrey was a man with a lot of options. One can appreciate the board’s desire to take some extraordinary measures to keep him,” Jack Stripling, a senior reporter at The Chronicle of Higher Education, told the Free Press. “The question is how extraordinary did those measures need to be.”

For the board, however, the compensation package was “money well spent,” according to Johnston. Over the course of 10 years, Kerrey had transformed The New School from eight disparate academic divisions to an institution of greater renown and with a much more unified academic identity. Kerrey’s time at The New School had seen the institution more than double both its endowment and annual operating budget. Kerrey had also significantly increased its number of degree-seeking and full-time students through an aggressive expansion of its undergraduate student base. And he had raised roughly $83 million in funds for the new 65 Fifth Ave. building almost entirely by himself — tapping into his vast network of contacts to draw the necessary gifts and donations.

Despite two student occupations, a faculty vote of no-confidence and his controversial support for the Iraq War, Johnston and the board had always maintained that Kerrey was the right man to lead The New School. Within the terms of Kerrey’s new contract, the message was clear — for all of the controversy surrounding Kerrey’s tenure at The New School, the board of trustees was immensely pleased with the job he had performed and was happy to reward him accordingly.

“Bob had been terrific. He’d grown the student body by about 50 percent, he raised $110 million for the university’s goals, and he started the University Center project and separately raised about $83 million for that,” Johnston said. “So we decided to give him a retention bonus, to hold him for the last year of his contract.”

“And I’m glad we did that,” Johnston added. “I don’t think we made a mistake.”

****

The extent of Bob Kerrey’s compensation, as both president and president emeritus of The New School, raises questions over the significance of his time at the institution – as well as the way that the institution functions at the highest level. There are questions over Kerrey’s worth to the university over the 10 undoubtedly transformative years he spent at its helm; the way The New School’s Board of Trustees went about awarding him a $1.2 million bonus without any input from faculty or students; and the value he currently holds to the university in his emeritus position while simultaneously attempting to reclaim the Nebraska seat in the U.S. Senate that he had vacated 11 years ago.

In an email to the Free Press, Kerrey confirmed that the MPAA was pursuing him at the time when the board of trustees decided to award him his lucrative compensation package. “[The board] decided to offer a retention bonus,” Kerrey told the Free Press. “I agreed, and remained to finish the fundraising and financing of the University Center.”

But the extent to which the board compensated Kerrey has held particular significance for a New School community coming to terms with a new, stringent economic reality. David Van Zandt, Kerrey’s successor, has had to implement a “strategic” financial plan at the university, in response to a $9 million budget shortfall for the 2011-12 fiscal year. The plan entails cost-cutting measures across the administrative level, as well as the pursuit of fewer faculty hires across all academic divisions. Van Zandt and Provost Tim Marshall even took a five percent cut in their own base salaries for the 2012-13 academic year to help the school operate within its means. Van Zandt has attributed the budget shortfall to the university’s failure to meet its enrollment growth targets, which were set during Kerrey’s term.

Van Zandt told the Free Press that he was not in a position to judge whether or not Kerrey’s compensation is problem for The New School in its current financial situation. “I wasn’t there negotiating the contracts, [so] it’s not really up to me to say whether or not in the current environment we should pay it,” Van Zandt said.

Yet Johnston’s assertion that the compensation package granted to Kerrey, even in hindsight, was “money well spent” goes some way to revealing the esteem with which the board valued his accomplishments at the university. Frank Barletta, The New School’s senior vice president for finance and business, joined the university shortly after Kerrey assumed the presidency in 2001. For Barletta, Kerrey’s positive impact on the institution was undeniable.

“Bob looked at the institution [when he arrived] and saw that it was pretty much a graduate school, for the most part,” Barletta said. “It didn’t have a large undergraduate student body, like most universities do.”

As a result of Kerrey’s commitment to expanding The New School’s undergraduate student base — from 3,721 students in 2001 to 6,374 in 2011 — the university “is much better off now than it was in 2001,” according to Barletta. Increased revenue from the student body expansion meant that The New School’s annual operating budget grew from $151 million in 2002 to $330 million in 2011, while the institutional endowment grew from $93 million in 2001 to $216 million in 2011.

For some within the university community, however, the lack of transparency in deliberating the former president’s compensation shown by the trustees is as alarming as the salary itself.

“We have a board of trustees that has no direct accountability to faculty or students,” said Nidhi Srinivas, an associate professor of nonprofit management at Milano and former co-chair of the University Faculty Senate. “There are no students who are representatives on the board of trustees, and there are no faculty who are representatives on the board of trustees.”

“Both are practices at some universities in the United States,” Srinivas added. “Given our university’s values, it would seem a healthy practice to enable such representation on the board.”

During Kerrey’s tenure, the board of trustees swelled to 54 members in 2006; by comparison, the board’s membership in 2011, after Kerrey’s departure from the presidency, had fallen to 42 members. Srinivas doubted the qualifications of some of the trustees, many of whom were brought in by Kerrey and eventually rewarded him his lucrative compensation.

“What Bob did after he came into the university is he expanded the board with his appointees,” Srinivas said. “And some of them did not seem to me people who either understand universities or who understand The New School; they seemed people who he believed had money and knew how to run a business.”

While Johnston has previous experience serving on the boards of educational institutions — he was chairman of Claremont Graduate University’s board of trustees from 1994 to 2001, and has served on the board of governors for both The New School for General Studies and The New School for Drama — Srinivas said that, in his experiences as a co-chair of the faculty senate, he was “at times astonished by how little certain trustees know about our university.”

“And this is the board that approved the decision on the retention bonus,” Srinivas added.

There is also the matter of Kerrey’s present role as president emeritus of The New School. At a town hall held by Van Zandt and New School for Social Research Dean Michael Schober in February, NSSR students questioned Van Zandt on the merits of Kerrey’s continuing presence on The New School payroll. At the time, Van Zandt refused to disclose Kerrey’s salary, describing the matter as a “privacy issue.”

But with a report from the Omaha World-Herald this spring revealing Kerrey’s salary as president emeritus, the figures are now public knowledge. In his new role, Kerrey has continued to work for The New School, most notably hosting a discussion with former Senate colleague Russ Feingold at Tishman Auditorium in February. According to The Chronicle’s Jack Stripling, he is also expected to continue raising funds for the university. But with Kerrey busy on the campaign trail in Nebraska, the value he currently holds to The New School in that role is up for debate.

“The question of whether Bob Kerrey can simultaneously be a fundraiser worth up to $600,000 a year, and also run a national campaign for senate,” Stripling told the Free Press, “is a fair question that should be asked at The New School.”

One fledgling student organization, The New School Disorientation group, has said that it intends to ask such questions. According to Lang senior and Disorientation group member Skanda Kadirgamar, the organization intends to “foster a growing awareness in [New School] students across divisions regarding the impact unchecked tuition hikes and rising debt will have on their futures.”

When asked for his thoughts on Kerrey’s salary as both president and president emeritus, Kadirgamar said he supposed that The New School’s position as a tuition-driven institution – one that generates 90 percent of its revenue from student fees – “means that students are ultimately accountable for padding the bill” for Kerrey’s post-presidential endeavors.

Leave a Reply