Student exhibition explores five blocks lost in time

In the Lower East Side of Manhattan, just south of the Williamsburg Bridge, the Seward Park Urban Renewal Area (SPURA) offers the tourist or casual passerby a rare tableau amid the city’s cluttered landscape: empty space.

SPURA, the largest undeveloped plot of land in Manhattan below 96th Street, has lain fallow for over 40 years. Now, as the city moves towards a final plan to build on the space, some Lang students have developed an exhibition considering the project as a case study in urban planning gone wrong.

Standing before some 50 people in the Arnold and Sheila Aronson Galleries, a small arts space in the Parsons building at 66 Fifth Ave., Gabrielle Bendiner-Viani, photographer, curator and professor of urban studies, described her work with The New School’s Urban Program, which aims to instruct students on approaching issues raised by steady growth in already-dense urban areas with creativity and understanding.

Among the persons present at the January 23 opening were the latest students of Bendiner-Viani’s Layered SPURA/City Studio, a course which has been ongoing since 2008. The gallery exhibit is the culmination of their semester’s work. Sounds of children playing and the rumbling hum familiar to any city-dweller emanate from an audio/video installation on the wall behind her. They lend a sense of place to her brief overview of a saga that has played out over half a century on the 25.9 acre tract of land in the Lower East Side.

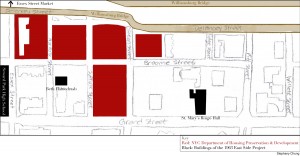

The tenement buildings that once stood between Delancey and Broome had been home to thousands of families. Beginning in 1949, a initiative begun by Robert Moses, New York City’s legendary master builder, many of these families were forced to relocate as part of urban renewal programs.

In the 1950s, hundreds of millions of dollars was earmarked for the demolition and rehabilitation of dozens of economically distressed neighborhoods across the five boroughs. In each instance substandard buildings were razed wholesale and appropriated by the City of New York under Title I of the U.S. Housing Act. The land was then sold to developers at a loss but with the stipulation that a mandatory percentage of new properties be reserved for Low-, Middle-, or Mixed-Income rentals all to be subsidized by a smaller amount of market-rate units.

In January of 1959, The New York Times reported that what was then known as the Seward Park Extension Project contained “738 houses, of which 698 [were] rated ‘substandard,’” and that $7 million had been allocated in order to demolish and rebuild the site. The 2,200 low-income residents of Seward Park would be relocated while new buildings were constructed. New development for the Seward Park Extension Plan was voted and approved in 1965.

However, not all were pleased with the final guidelines set out by the Housing and Redevelopment Board. Over the next five years the plan ground its way through the gears of city, state and federal housing authorities, followed at every tooth by vocal opposition from the original low-income residents of SPURA, who felt as though the promise for a higher allotment of affordable housing had been steamrolled along with the buildings they had once called home.

During the 1970’s, development slowed to a crawl. Fierce legal battles between different ethnic groups, all claiming the space as their own, made politicians wary of taking sides. Most notably, Puerto Rican families had made around 60 percent of the pre-demolition population, but had only managed to obtain 22 percent of the remodeled units. The federal government issued a freeze on commitments of housing funds until the debates could be settled. Work on the project came to a halt.

The next time SPURA appeared in the news the headlines were familiar. According to a article published by The New York Times on March 12, 1980, “A group of mainly Hispanic organizers wants low-income housing… A coalition of Jewish organizers wants a shopping mall, to create jobs…and the Chinese-American social service agency wants a project to house some of the thousands of elderly Chinese workers living in tenements a few blocks away.” This dispute ended with the quick approval for two of the three development proposals. Chinatown’s elderly would be provided a 150-unit building, and the commercial development along Delancey Street would proceed. But much of the project remained empty.

Some 32 years later, not much has happened.Many of the original low-income residents promised the right to return have died or moved on, and SPURA, frozen in time, has become a source of speculation for city planners and residents alike. Now, Lang students are chronicling the history of the troubled project to try to find a path forward.

Under Professor Bendiner-Viani’s guidance, Layered SPURA allows student participants to join local arts and community groups such as Place Matters, Good Old Lower East Side (GOLES), the Pratt Center for Community Development, and Jews for Racial and Economic Justice in exploring the history, and imagining the future, of this seemingly innocuous strip of real-estate located on the Lower East Side.

The large parking lots flanking the 24 hour traffic of East Delancey Street from Clinton to Essex are not the breathtaking examples of Art Deco or Second Empire history that New York sightseers are used to, but the art of Layered SPURA invites us to visualize the invisible history of this Lower East Side landmark. The exhibit leads us further: through a series of interactive installments we’re placed front row, to witness the sights and sounds, the life, of the Seward Park Extension.

Framing SPURA, a visual piece created by students Amy Nguyen, Matthew Taylor and Corey Mullee with John Lake, features a panoramic photograph of the contested tracts as they now stand. A series of framed transparencies sit in holders beneath the panorama, each one affixed with different images and items representing the history of SPURA, its current state of nebulous potential, or the potential consequences posed by various land use proposals that have come and gone over decades of public and political furor.

Nearby, “42 Years Later, and Still Waiting,” a video installation by students Anke Hendriks, Kaushal Shrestha, and Lila Knisely, follows Edward Rudyk, a pre-demolition resident of the Seward Park Extension. We hear him speak about the community as it was before Moses and company arrived: depressed, and crowded, perhaps, but thriving; a home nonetheless. Since before the Civil War, turmoil has roiled the Lower East Side. In the last half of the 19th century, the district became known as the city’s melting pot — home to the flood immigrants and low-income families. But in the decades before World War II, it also gained new renown, as a vibrant cultural center for art and music.

Today, after 50 years of debate, the City of New York may have found a way forward for the troubled area. Under new guidelines for development, SPURA will see 500 market-rate units built alongside 500 affordable housing units, split into the designations of middle, moderate and low-income. Currently, however, only 1 percent of SPURA residents would be able to afford housing at market rates, while the 300 units marked as low-income will be sought after by over 53 percent of the population.

Assemblyman Sheldon Silver, a longtime Lower East Side resident and champion of affordable housing, was one of the forces in Albany behind the new plan. In January of 2011 Silver offered high praise for the recent proceedings. “The final guidelines that were approved by the committee tonight,” Silver wrote in a statement published on his website during the same month, “strike an appropriate balance between the needs and concerns of all stakeholders and will result in a development that will ensure our neighborhood continues to thrive.”

Many long-term residents in the community, however, feel that the slated 50/50 split for market rate and affordable housing will leave the city’s promise to the 2,200 families removed from the original SPURA site unfulfilled.

But with so many development plans stalled over the years, it remains to be seen whether this latest one will gain the traction it needs.

Back on Fifth Avenue, when one visitor at the show wondered about her goals for the project, Berdiner-Viani paused, as though caught off guard.

“This exhibit,” she said, laughing at the simple answer, “The goal is this exhibit. To see what will be built at the site, and to make the issues here more visible. There’s a great deal of misinformation, and little conversation between people with divergent views and expectations. In the end the answers will have to come from within the the community itself.”

Reporting by Henry Miller and Erika Vaatainen

How the LES was won. (Or not.) from New School Free Press on Vimeo.