New law promotes corporate responsibility

Whether they are sidewalk markets selling organic, locally-grown produce or apparel companies taking stands against child labor, scores of businesses across America are pledging to help the communities they serve.  As the result of a new law signed on December 12, businesses in New York State will soon be able to donate money to social and environmental causes without worrying about lawsuits from shareholders focused solely on individual profit.

As the result of a new law signed on December 12, businesses in New York State will soon be able to donate money to social and environmental causes without worrying about lawsuits from shareholders focused solely on individual profit.

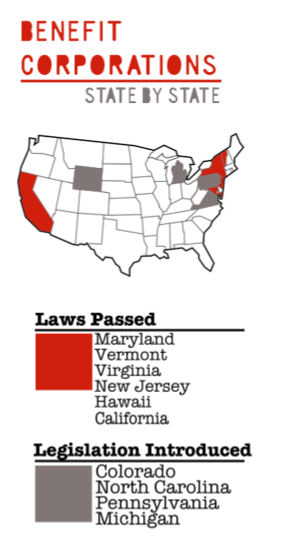

The Silver-Squadron Act, which takes effect on February 10, will make New York the seventh state to ratify such legislation.

Over the past two years, Maryland, California, Hawaii, Vermont, Virginia and New Jersey have passed similar legal protections. Supporters throughout the state believe the law will add much-needed momentum to a national discussion about socially conscious enterprises.

“It assures entrepreneurs and managers that their dollars are going to bring them financial return and also social return,” said State Senator Daniel Squadron, the 32-year-old Brooklyn Democrat who co-wrote the bill. “This is a great combination of being connected with the community and unlocking the entrepreneurial spirit.”

For David Bolotsky, 48, founder of the Brooklyn-based UncommonGoods, the law will mean a chance to create a more balanced ratio of profit and purpose.

Bolotsky grew up on the Lower East Side of Manhattan; his grandfather ran a nearby candy store, while his father worked for the United Nations. He was raised a student of both business and public service at work. In 1999, he founded his own online store, which features merchandise ranging hollowed-out cantaloupe bowls to wooden walruses, in support of local artists and manufacturers. It was a major professional shift for the man who had previously spent twelve years as a research analyst at Goldman Sachs, with a mandate, he says, to predict the future.

“‘Often wrong, never in doubt’ was our motto,” he recalled. “I found it fascinating, but it lacked a spiritual meaning. If I had stayed there, I would have gotten locked in with golden handcuffs.”

Bolotsky saw his future in donating money to causes around the city, including hunger and bicycle transportation. But because he was unfamiliar with starting a nonprofit organization, he built the startup around what he knew best — money. While much of UncommonGoods’s profits go to the workers making these products, Bolotsky also sets funds aside for City Harvest and Million Trees NYC, along with other organizations.

“There weren’t any businesses that really addressed social, economic and environmental issues in a holistic way,” he said. “There’s no reason why business has to be portrayed as this evil thing.”

In recent years, businesses like UncommonGoods have begun gaining support from investors as well. According to a May 2010 study from San Francisco-based strategy firm Hope Consulting, more than $120 billion is available nationwide in potential investment capital for benefit corporations and other American mission-based companies.

As demand grows for companies to operate as benefit corporations, third-party organizations, like the non-profit B Lab, aim to ensure that these companies report their social progress within the first 120 days of each fiscal year.

B Lab was founded in 2007 as a network of 81 socially driven businesses, or “Certified B” corporations. Today, more than 500 of these companies exist across the country, in industries ranging from agriculture to housewares to publishing.

“There is a huge generation of millenials who don’t want to work at companies that don’t reflect their values,” said Andrew Kassoy, co-founder of B Lab. “Investors can use this as a tool for accountability, and businesses can use this as a way to grow without compromising that mission.”

Through these third-party regulators, benefit corporation bills have received extensive bipartisan support, receiving a total of 892 ayes and 62 nays from legislators, as of December.

“This law features a great political mixture,” Andrew Greenblatt, who helped write the Silver-Squadron Act and teaches social entrepreneurship at New York University, told the Free Press. “Those on the left are happy because it protects corporations focused on social and environmental issues, and for those on the right, it does so without regulation from the state.”

Greenblatt once worked as a financial consultant for Ben Cohen, best known for co-founding the ice cream company Ben & Jerry’s. Before British-Dutch conglomerate Unilever bought his business in 2000, Cohen focused on increasing profit for employees and shareholders alike, working on social initiatives that were not capital-based. One such program offered non-profit urban youth organizations the chance to start their own ice cream franchises and raise money within their communities.

The program was not publicized, nor did it raise money for stockholders. Following much debate, the business’s hesitant loyalists and its eager shareholders completed the $326 million sale in April of that year. The company’s stock price rose to record highs, while many of its social projects were discontinued.

“What happened to Ben & Jerry’s is the case study for what we are trying to prevent from happening,” said Greenblatt. “Had they been a benefit corporation, that would not have happened.”

But despite existing potential for social and environmental change that these businesses provide, critics feel they are impractical within a largely capitalist framework.

“The essence of capitalism lies in knowing that companies not delivering profit will not stay in business,” said Charles Elson, a corporate law professor at the University of Delaware. “There is no point investing in a company in which you get little to no return; they will disappear before getting a chance to benefit anyone.”

Chris Crews, a politics major at The New School for Social Research and a board member of the Advisory Committee on Investor Responsibility, believes that current standards for benefit corporations are too low. He noted that, as part of B Lab’s certification process, companies only have to score 80 points out of a possible 200 during the initial assessment.

“If a benchmark says you are doing a good job by only meeting 40 percent of the target, that is not much of a standard,” said Crews, “no matter how big the Occupy movement or the socially responsible investing community grows.”

Those who continue to support benefit corporation legislation nationwide stress that time will let the flaws figure themselves out.

“We need to go into this consciously willing to pay attention and be supportive, alert, and aware of what’s going on,” said William Clark, a corporate attorney with Philadelphia-based firm Drinker, Biddie and Reath. “This is a very new concept, so we’re going to see how it evolves.”

In the months to come, benefit corporation bills will be moving through more state legislatures throughout the country, including those in North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Michigan, as well as in the District of Columbia.

Reporting by Jill Heller.

Leave a Reply