On February 2, officers from a New York Police Department street narcotics squad kicked down the door and raided the home of 18-year-old Ramarley Graham. The officers were canvassing the Wakefield area of the Bronx — known to be a hotbed for drug trafficking — and spotted Graham purchasing a bag of marijuana.

According to the officers, the way Graham adjusted his waistband as he left a convenience store led them to believe that he was armed. They followed him to his grandmother’s apartment and, guns clutched, entered. Graham heard the police and headed toward the bathroom to flush the pot down the toilet. In the turmoil, an officer shot Graham in the chest, killing him instantly. Graham was unarmed.

It didn’t take long for the story to make its way to the media, and it wasn’t the first time that a police killing made the headlines. In 2006, undercover NYPD officers shot three men 50 times in Jamaica, Queens, killing 23-year-old Sean Bell. The policemen, who allegedly opened fire because one of the officers heard someone utter the word “gun,” were found not guilty for Bell’s death. There was also the infamous case of Amadou Diallo, an African immigrant living in the Bronx, who police officers shot 41 times in February of 1999. Diallo allegedly fit the description of an armed serial rapist, and was stopped by police. When he reached for his wallet, the police believed Diallo was reaching for a weapon and responded by dousing him in a torrent of bullets.

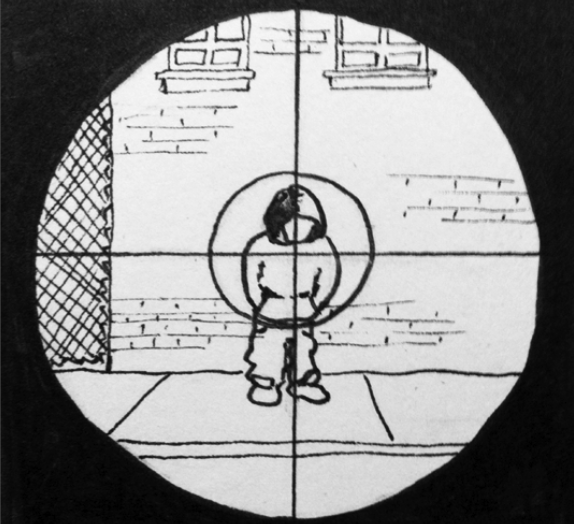

While incidents like these don’t take place every day, they can be interpreted as separate components to a much bigger problem: the disconnect and lack of dialogue between police officers and the broken communities they are sworn to protect. On a daily basis, NYPD officers are confronted with perilous environments, life in disorder, and societal decay. They have a firsthand account of the issues that cripple poor neighborhoods — issues like drug abuse, unemployment and generational poverty. Unfortunately, many of them respond to these issues by treating the residents of crime-ridden neighborhoods like enemies in a war zone. No one is innocent — everyone is a suspect. This attitude breeds a spirit of scorn and hostility between the police who patrol these neighborhoods and the people who are trapped there; an atmosphere of mistrust and suspicion permeates, and, as a result, the police overreact when they feel they are in danger. Such was the case with Diallo, Bell and Graham.

The disconnect between police officers and residents seems to stem from their contrasting backgrounds. Many NYPD officers come from a different neighborhood and are of a different ethnicity than the residents who occupy these crime-ridden communities. Awkwardly placed in an environment that is alien to them and populated by a racial “other,” police officers adapt a dangerous mentality. Anthony V. Bouza, a retired police officer of 40 years who once served as commander of police in the Bronx, writes about this in his book, “Police Unbound: Corruption, Abuse, and Heroism by the Boys in Blue.”

“There is a clear, yet subliminal, message being transmitted that the cops, if they are to remain on the payroll, had better obey,” writes Bouza. “The overclass — mostly white, well-off, educated, suburban and voting — wants the underclass — frequently minority, homeless, jobless, uneducated and excluded — controlled and, preferably, kept out of sight. Property rights are more sacred than human lives.”

Being displaced in potentially dangerous neighborhoods and pressured by society to control crime leads police officers to commit acts of violence and incidences of indignity. The unconstitutional “stop and frisk” searches are perhaps the most obvious example of this: in 2011, the NYPD stopped and searched more than 500,000 New Yorkers, 85 percent of whom were black or Latino. Less common, but more tragic, are police shootings.

One cannot have soldiers walking among civilians. Many police officers seem to adopt a combative siege mentality towards people living in derelict communities, forgetting that they are just that: communities, not warzones. War tactics and guns simply don’t work in residential neighborhoods, no matter how destitute. Busting down doors, slapping on handcuffs, and writing tickets may look good for a police officer’s annual quota, but do nothing to create a safer environment or to address the larger social ills at play.

“Some lives are more precious than others,” write Bouza, discussing the viewpoint of police officers. Therein lies the crux of the problem: The police aren’t trained to see residents of these neighborhoods as people, but as suspects. They are not taught to consider the societal ills that prompt crime and violence. Guns and tactics should be part of a police officer’s training — after all, they are necessary at times for such a stressful and dangerous job — but these should not be the only methods. Matching violence with violence will only increase hostilities.

Maybe if the government shifted its focus from incarceration to rehabilitation, police officers wouldn’t be so quick to jump on nonviolent drug offenders. And maybe if the NYPD didn’t force its officers to fulfill quotas, they wouldn’t prowl the streets and make arrests that, more often than not, won’t even make it to trial. We should stop pressuring police officers to make arrests and teach them that they are not soldiers but civilians — civilians with an important chance to improve society. Most importantly, we should find ways to promote positive interactions between police officers and the communities in which they work. Open discussions would foster more understanding, and would, eventually, break down the “us vs. them” mentality that has permeated these neighborhoods for far too long.

If things don’t change, what happened to Graham, Diallo and Bell will happen again, and police officers and residents of crime-ridden neighborhoods will be forever locked in a battle where no one ever wins.

Leave a Reply