Remarks of civil rights leader among several found in New School archives

In the spring of 1964, The New School played host to one of the most impressive speaker series in its history. A university-sponsored lecture series brought out hundreds to The New School Auditorium on West 12th Street — now Tishman Auditorium — to hear 15 of the most prominent civil rights leaders of the era.

For the price of tuition — $40 for non-degree students — students could attend the two-credit class and hear some of the movement’s titans lecture and answer questions. The Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. opened the series on February 6, a little more than five months after his “I Have a Dream” speech in Washington, and only four days before the Civil Rights Act passed the House of Representatives. King was followed in the series by notables who included NAACP head Roy Wilkins; actor and activist Ossie Davis; socialist Bayard Rustin; Robert Weaver, the first black U.S. cabinet secretary; and James Farmer, co-founder of the Congress of Racial Equality, as well as nine other scholars, organizers and activists.

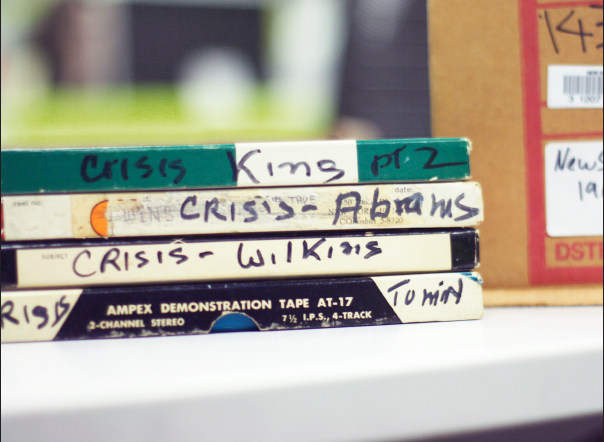

But in time the talks — collectively known as The American Race Crisis Lecture Series — were forgotten, and the reel-to-reel recordings made of the seminars were locked away in an archive, their existence recorded in inventories but long since lost to history. After nearly half a century, a small collection of the tapes has surfaced, the result of a year-long effort by students, faculty and archivists.

A few of the tapes, including a portion of King’s address on February 6, have been digitized. The tapes, which Professor David Levering Lewis, one of the foremost scholars of African American history, calls “a really felicitous find,” provide the only known record of a seminal moment in both the history of the civil rights movement and the history of The New School.

****

When New School for Social Research doctoral candidate Chris Crews started to do research for a presentation on the politics of desegregation in New York City in the 1960’s, he found a press release from The New School’s communication and external affairs office — the kind most students look over and discard. A photograph caught Crews’s eye, a speaker at the podium in the university’s distinctive Tishman Auditorium.

“That sure as hell looks like Dr. King,” Crews remembers thinking.

It was the start of a year-long effort involving individuals and resources from across the school. In late summer of 2011, Carmen Hendershott, a university librarian, located old copies of the New School Bulletin, an alumni newsletter, confirming King’s appearance at the school.

But traces of the talks had seemingly vanished.

A search for materials relating to the seminar ensued. Last fall, the prize emerged: in a section of Fogelman library’s archives, a box of reel-to-reel tapes — one labeled with the the phrase “MLK Part 2.”

But with the tapes found, there was no money in the library’s budget to attempt to recover or digitize the tapes. Only after Crews, the treasurer of the University Student Senate, secured $800 from that body last September, three and a half tapes were sent offsite for analog-to-digital conversion.

Nearly a year after Crews first saw the picture of King at the podium, the effort and time invested in locating and recovering the tapes has borne fruit. Three and a half of the lectures have been recovered, and are now available in high-quality audio online, thanks to the efforts of the Kellen Design Archives.

They include the entirety of the speech given by Roy Wilkins, then the recently-named executive director of the NAACP; Melvin Tumin, a white Princeton sociologist who spent much of his academic career studying race relations; and Charles Abrams, an urbanist who founded the New York City Housing Authority and who spoke at The New School about the issue of housing discrimination.

Among the tapes restored is half of King’s address. The recovered recording contains an excerpt of the Q&A session that followed King’s opening address, in which the civil rights leader candidly addresses the Black Muslim movement of Malcolm X, Lyndon Johnson’s intentions regarding the Civil Rights Act, and the perceived slowdown in the Civil Rights movement that followed the 1963 March on Washington.

The King Center in Atlanta told The New School Free Press that it could not find a transcript of the address, nor any record of it taking place. The digitized tape is perhaps the only surviving evidence of King’s speech that night.

****

NYU Professor David Levering Lewis, the two-time Pulitzer Prize winning historian who authored the first academic biography of King in 1970, called the trove of tapes “really quite a find,” especially the King tape, which, “because of the timing of the questions he’s responding to, has a more distinctive importance to it.”

The American Race Crisis Lecture Series was held over several months of dramatic change in the direction of the civil rights movement. As such, the New School tapes have considerable value as historical documents — and the King tape, in particular, has a “distinctive importance,” said Lewis.

King gave his lecture just four days before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 passed the House of Representatives, and spoke about Malcolm X a little more than a month before the Black Muslim leader went on his Hajj.

“He responds in a rather tactful and balanced way to the issue of the Black Muslim movement, and its just on the eve of Malcolm X’s visit to Mecca,” Lewis said. “It provides a kind of before and after perspective.”

But Lewis puts King’s remarks in the context of a much more significant change happening in the movement.

“We’re approaching the great divide that historians are wont to describe. We’re coming to the end of denouement, the lunch counter desegregation era, where the formal structure of apartheid is going to be demolished,” Lewis said. “And for the most part the drama had been regional, located in the former confederacy. And after the voting rights act of 1965, the drama moves north and west, and at that point the issues become more complex.”

In the tape, the moderator is heard to ask King if he considered “preferential treatment of the Negro… a solution in any way to the race problem.”

King gave a lengthy defense of what is now called affirmative action, invoking a conversation he had with then-Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru about the efforts of the Indian state to ameliorate the suffering of the Untouchables, the lowest members of the Indian caste system.

Lewis said the question catches King – and the movement – in a moment of transformation.

“When the demands turn from seating at lunch counters and towards economic empowerment, that sort of thing, [the movement] is going to be less supported by people across the nation,” he said. “We know that King is moving in the direction that will and does in fact radicalize a vast portion of the Civil Rights movement.”

****

But the other speakers are also caught at a particular moment in time.

Wilkins spoke days before the 10th anniversary of the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown vs. Board, and exhaustively addressed the pace of school desegregation in his speech, turning to attack the then-Republican Presidential Frontrunner Barry Goldwater.

Of particular interest is his accounting of W.E.B. DuBois’ forced departure from the NAACP, after DuBois drifted leftward in the early years of the Cold War. Lewis, whose two-volume biography of DuBois won two Pulitzers, said Wilkins’s answer records his difficult balancing act as head of the Civil Rights movements’ largest organization.

Wilkins was “the mouthpiece of a very cautious institution,” said Lewis. He was “certainly unfriendly to the left, and that’s an understatement. But it was a situational thing rather than a personal thing,” Lewis added, an accommodation necessary to maintain the NAACP’s veneer of respectability and moderation.

Abrams addressed contemporary political battles over California and New York City’s housing desegregation plan.

The New School’s Kellen Design Archives — the best-funded and equipped branch of the school’s decentralized archive system — have hosted the tapes, along with transcripts, for scholars and the public to peruse on their website. The tapes are a reminder that much of the schools’ vaunted history remains waiting to be rediscovered.

Audio: Martin Luther King

The tape, 15 and a half minutes long, opens with King responding to a question about President Lyndon Johnson’s commitment to the civil rights movement, and the Civil Rights Act, which at the time was being negotiated in the House of Representatives.

Then, a questioner asked King if Malcolm X and the Black Muslim movement could make a positive contribution to the civil rights movement. It depends, King said, on what ‘positive contribution’ means.

“It may frighten some people enough to cause them to see that we better hurry up and get this problem solved. They think of me as a pretty bad fellow down in Georgia and Alabama and Mississippi and say a lot of bad things about me, but even I’ve become a little more respectable when they discovered some of the ideals of the Muslim movement,” he said to laughter in the audience. “I disagree with the philosophy of this movement […] We should never seek to rise from a position of disadvantage to advantage […] substituting one tyranny for another.

“But I do feel that this movement does remind the nation of something. And if in reminding the nation of this something that it so desperately needs to hear and to know, there may be some contribution.”

To a question asking why the civil rights movement had seen a “bog down” since King’s fabled march on Washington, King offered a prediction which would ultimately prove correct.

“We will see more intensified activity in the civil rights movement and the movement will gain even greater momentum in 1964.”

Later, he argues in favor of “preferential treatment for the Negro” as a necessary means for economic empowerment, recalling a recent trip to India, and a conversation with Prime Minister Nehru.

“Even in this poor country, the government spends millions and millions of rupees a year to improve the lot of the Untouchables. And then [Nehru] went on to say if two individuals apply for a university, one an Untouchable, and one a member of the higher caste, and they don’t have but one opening, that university has to accept the Untouchable. I said, ‘Well now, isn’t this discrimination in reverse?’

[Nehru] said, ’It may be. But this is our way of atoning for the thousands of years of sins and injustices that we have inflicted on these people.’

I think America some how must face her moment of atonement. Not just atonement for atonement’s sake, but we must face the fact that we’re going to pay for it somehow. If we don’t do it, we’re going to pay for it with the welfare rolls, we’re going to pay for it in many other ways. And I think that this matter of preferential treatment is just a way of saying that som e crash program must be developed to improve the lot of the Negro.”

MELVIN TUMIN

FACTS AND FICTION IN HUMAN RELATIONS

MARCH 19, 1964

Audio: Tumin lecture

Tumin was a Princeton Sociologist who studied race relations, and spent much of his academic career exploring the roots of bigotry and racism, as well as debunking scientific claims of biological inferiority between races, two subjects that constituted the main focus of his address. His 1958 study “Desegregation: Resistance and Readiness” on the attitudes of white residents of Guilford County, North Carolina, became one of the preeminent academic works on desegregation and its effects.

Addressing the recent comprehensive plan to desegregate New York City schools, he said that very little of the conflict predicted by pro-segregationists would actually pass. But the failure of these predictions will have little effect on the “true believers,” even in his native Princeton.

“Just seven days ago, a group of students on my campus announced a formation of a new organization called Students for Segregation,” he said to laughter.

“Their avowed purpose was to tell the truth about Negro/white differences, and to demonstrate with that truth that not only was the demand for total and immediate desegregation or integration of the schools, not only was that demand not justified by the facts, but indeed there was a serious question, said these students, as to whether any desegregation could ever be justified.

“One should hasten to say that the response to this organization from other students, faculty, and administration was such as to discourage all but the most hard‐bitten of the hard core. But that’s not important, and in any event, it would not be a very meaningful observation, since it is characteristic of the true believer, wherever he is found, that he flourishes on opposition and hostility, especially if it’s public.”

“He is beautifully well‐insulated, the true believer is, by his faith, whatever its psychological origins. He’s insulated against the possible impact of contradictions, whether these be contradictions of his moral point of view or of the so‐called evidence that he offers in support of that point of view.”

CHARLES ABRAMS

UNSETTLED ISSUES IN THE CITIES

MARCH 26, 1964

Audio: Charles Abrams lecture

Audio: Charles Abrams Q&A

Abrams, a Greenwich Village landlord and urbanist who founded the New York City Housing Authority in 1934, spoke about plans for and conflict surrounding housing desegregation. A New Deal veteran, he was a crucial part of the effort to lobby President Kennedy to ban discrimination in federally subsidized housing projects, which had long-lasting repercussions in cities in the Northeast.

Abrams begins by talking about the contemporary social effects of urbanization all over the world. He spoke at length about the ways housing discrimination had been ensured by the Federal Government since the creation of the FHA, comparing them to the Nuremberg Laws. But he also spoke out against some efforts — especially those in California — that impose criminal penalties on private citizens who attempt to maintain segregated housing.

“In each case — and this has been my experience in New York State — in each case, you try to make advances which can be absorbed, which are workable, which are practical. I think it’s foolish to try to go ahead and — I mean, to advance, for the social reformer to advance in chaos while the bigot is retreating in good order.

I think that there’s an obligation to be practical, and I think that it was this effort to impose a criminal penalty suddenly to a community that wasn’t ready for it, that lost some of the people who were generally in favor of such a law.”

ROY WILKINS

UNTITLED/TITLE UNKNOWN

MAY 14, 1964

Audio: Wilkins

Audio: Wilkins Q&A

By 1964, Wilkins had been involved in the NAACP for decades. He had taken over as editor of The Crisis, the organization’s magazine, after W.E.B. DuBois had left the organization in 1934. He was the NAACP’s executive secretary since 1955, and when he came to Tishman Auditorium he was the group’s newly-minted executive director. He helped organize the March on Washington in 1963, and the March from Selma to Montgomery in 1965. He was known within the movement for his staunch opposition to leftists, and his conciliatory and gradual approach.

He spent much of the first part of his speech addressing progress in school desegregation, noting that the 10th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education was on May 17, 1964.

Later, he attacks Republican frontrunner Barry Goldwater in the strongest possible terms for his policy on civil rights.

“Whether he intends it or not, Senator Goldwater’s position of leaving civil rights matters to the states grants immunity to the use of cattle prods and shotguns by Alabama state troopers, the armored tank and dogs and fire hoses of Birmingham police, the bomb murders of little children in churches in Alabama, and the assassination of Medgar Evers in Jackson, Mississippi last June.”

Then, to a questioner who asks what can actually be achieved by the movement in the face of widespread white resistance, Wilkins delivers a passionate rebuttal.

“This question puzzles me a little. In the first place, it seems to acknowledge acceptance of the view that resistance or opposition should either change your objective or cause you to cease your activity.”

“Negroes died on Boston Common, fighting in the Revolutionary War. Three thousand Negro soldiers were under George Washington at Valley Forge and Appomattox. They helped to defeat the British. He belongs to this country, and the country belongs to him. And who is going to come along in 1964 and say, ‘Well, white people object to this, so what are you going to do?’ We’re going to continue to take what belongs to us, that’s what we’re going to continue to do.”

http://www.newschoolfreepress.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/ARC_PressReleases.pdf

Leave a Reply