In the Village, a redoubt of gay culture faces the future

Since a fire destroyed his apartment more than three years ago, Landon Davenport has been vigorously searching for a new place to live. On a warm Thursday night, he sits at the hardwood table he calls his own — the third-farthest from Julius’ tavern’s entrance — flipping through the newspaper classifieds and circling options with a red pen as he eats a burger and fries. The bar, located where Waverly Place and West 10th Street meet, has been his second home since 1973.

“They were the days of platform shoes, Mott the Hoople, and sweet, luscious hair,” said Davenport, an “over 40” former literary agent. “It is home to wonderful conversations with gorgeous people.”

But since then, many of the young men and women who came seeking the freedoms of the West Village — and who comprised the core of the American gay rights movement — have left for good. The area was once the home of folk musicians and anti-war demonstrations. Today, wealthy residents of magnificent townhouses predominate. And while millions of tourists step into Magnolia Bakery and Washington Square Park each year, Julius’ remains a hidden relic. With its rustic carriage wheel chandeliers hanging from the ceiling, its decor resembles the western saloons of the 19th century, safe from gentrification for now, but not immortalized like its neighbor, the Stonewall Inn.

“If somebody were to come up to me and ask where the gay life in New York City is, I would have no clue where else to direct them,” Davenport added. “Gentrification is forcing a long goodbye to the independent businesses of Chelsea and Greenwich Village.”

****

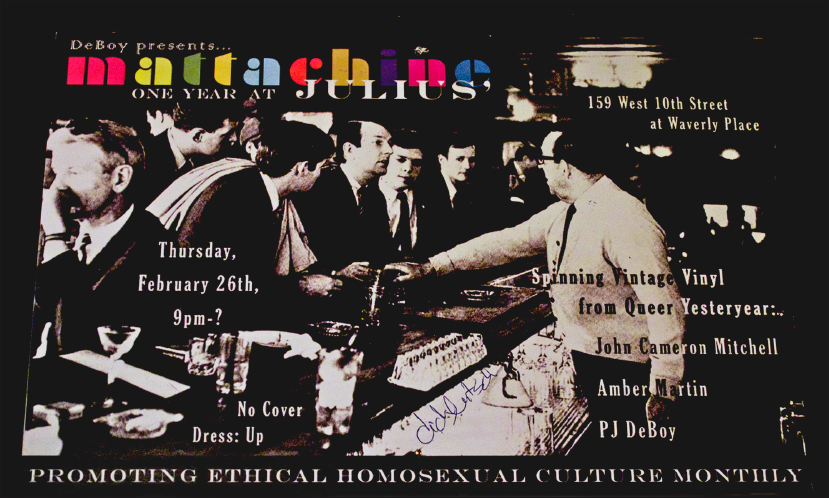

Every third Thursday of the month, over a hundred gay men gather inside the bar for Mattachine Night. DJs play records on their turntables. Patrons stand in circles with drinks in hand, chatting about the sounds of Miles Davis and the textures of sourdough bread.

Together, they commemorate the Mattachine Society, the second-ever homophile organization in the United States, and its 1966 “sip-in” at Julius’, inspired by the civil rights sit-ins staged earlier that decade.

On April 26 of that year, three gay men — Mattachine Society president Dick Leitsch, along with members John Timmons and Craig Rodwell — and five reporters walked up to the tattered bar’s counter and challenged the New York State Liquor Authority’s law prohibiting openly identifying homosexuals from ordering alcoholic drinks in bars.

We are homosexuals,” the note read. “We are orderly, we intend to remain orderly, and we are asking for service.”

The bartender began making the men drinks, but after noticing the reporters, understood that they were looking for a photo-op. He played along and denied them service. An April 27, 1966 headline in The New York Times read “3 Deviants Invite Exclusion by Bars.”

“Homosexuals couldn’t get anything before the sip-in,” Leitsch told the Free Press. “At bars, we were often stopped at the doors. And any place that dared to serve us got raided or shut down.”

The “sip-in” at Julius did not overturn any government rulings. But it would later prove a catalyst for the birth of the gay rights movement, most frequently remembered by the Stonewall riots three years later at the West Village bar two blocks away. But Julius’ longtime patrons say that without the 1966 event, other popular gay establishments like the Stonewall Inn would never exist.

****

Although the tavern opened in 1864, Julius’ did not attract a gay clientele until the 1950s, when openly homosexual men and women were banned from government employment and same sex couples could be institutionalized or castrated for having intercourse. And in 1953, President Eisenhower signed an order deeming “sexual perversion” — including homosexuality — grounds for employment termination.

Los Angeles-based gay rights activist Harry Hay founded the Mattachine Society in 1950. Seven years later, in 1957, members of the organization formed a New York City branch. Fewer than a hundred New Yorkers joined the regional group in its first year. But with the formation of rally cries like “gay is good” and “gay power” in the 1960s, activists began to emerge, and events like the Julius’ sit-in and the Stonewall riots soon defined Greenwich Village’s role in the movement.

“The monster of repression haunted us for so long, and the riots were a turning point for us,” recalled Tom Bernardin, a self-proclaimed historian of Julius’. “Sure, we have gone through a lot of heartache since then — homophobia and HIV/AIDS are still way too present — but the spirit of what happened there should always remain.”

Bernardin often spends his early mornings sweeping the gutter outside the bar. He started frequenting Julius’ in 1974, when the clientele was mostly college students.

“We were kids with sweaters draped against our shoulders,” he said. “But we knew a community when we saw one.”

With a pint of beer in his hand, Bernardin recalled one of the West Village’s darkest times. “Most of my peer group is wiped out. AIDS took care of that,” he said. “But patronizing this place during a time when we needed them, and they needed us, was one of the best things that happened to me.”

In the 1980s, at the height of the AIDS epidemic, Julius’ stood just two blocks away from St. Vincent’s Hospital, which treated more AIDS patients than any other city hospital. Like many Greenwich Village establishments, St. Vincent’s has fallen prey to the high value of the local real estate. The hospital, which opened in 1849, is now being redeveloped as elite condominiums.

But while much of the village has faltered in recent years, Julius’ brings together members of the gay community — young and old — around one of the neighborhood’s longest-standing displays of their culture. Longtime bar-goers claim that business has nearly quadrupled over the past three years, as a new generation of patrons appears.

“Even though I’m young now, I would feel just as happy coming here as an 80-year-old,” said Patrick Emmanuel, 30, who has been visiting Julius’ for a year. “You live in New York to experience all of life’s permutations. I feel part of a community. It is not something that happens often for homosexuals.”

Davenport claims that his luck has not always been ideal. He has been struck by lightning on the Matterhorn and was bitten twice by black widow spiders. But even as new patrons begin frequenting the bar, events like Mattachine Night help retain his confidence in the landmark’s future.

“Independent businesses give our community flavor,” he said. “Here, as long as the kitchen is open, I will always have a place to sit.”

Reporting by Miles Kohrman & Stephany Chung

Leave a Reply