Since the eviction of Zuccotti Park during the misty, early morning hours of November 15, the Occupy Wall Street movement has been in a state of lulled hibernation. Despite assumptions that their 15 minutes of fame had passed, Occupy organizers have spent the winter months carefully studying and planning where to go next.

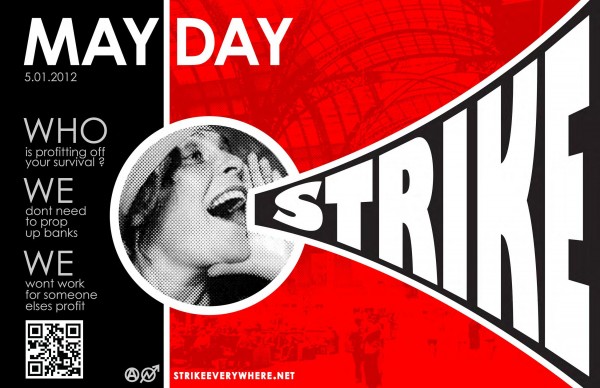

Now, as the winter has thawed and summer draws nearer, OWS is ready to return to the limelight. On May 1, the movement will once again attempt to present itself as relevant and powerful social and cultural force. Hoping to bring a strong revival to the history-rich occasion of May Day, organizers are planning a culmination of teach-ins, marches, and “pop-up occupations,” in a day of action which is slated to be the unofficial test of Occupy’s true longevity and impact.

“When you talk about what it would actually take to affect the systemic problems of economic inequality, you are talking about something that looks like a revolution,” said Katie Davison, a documentary filmmaker from Los Angeles. Davison flew out on a red-eye flight to join Occupy in the beginning of September, during the movement’s earliest days. She planned on staying for the weekend.

Davison’s opinions, like those of all individuals who discuss Occupy Wall Street, are not interchangeable with that of the movement as a whole. Yet in the spirit of the General Assembly — the collective decision-making phenomenon which those involved have grown to know intimately – these individuals offer a well-versed perspective on the question of how Occupy can best address the problem of economic inequality it has so vehemently raised. To the general public, however, the question remains: what, exactly, is the problem?

I sat down with Davison and her friend, Tom Hintze, in Davison’s homey apartment on the Lower East Side to get an idea of what lies ahead for the movement, given its apparent dormancy over the winter months.

Davison and Hintze have been involved with OWS since its inception, and have worked in various affinity groups such as Direct Action; Plus Brigades, a creative disobedience group; and Tidal magazine, the new publication by the group Occupy Theory. Hintze also helped in the upkeep of the “free kitchen” at Zuccotti Park, from the early days of the occupation right up to the eviction.

“I think this is going the be the transformative movement of the 21st century,” Davison said without a moment of hesitation when asked for her comparison of Occupy to other generations of activists and rights groups.

OWS seeks “to be the radical tip of the spear that forces change in our wake,” Hintze said.

He was commenting a sentiment that Davison had expressed earlier, relating the potential of Occupy to that of the Civil Rights movement — which strove for overarching social equality, and left “success that is tangible in the wake of the movement itself,” according to Davison.

At this point in Occupy’s history, such a comparison may come as a bit of hyperbole to an outsider. But once we began to discuss the movement’s plans for the next few months, and how it might effect the November presidential elections, it was clearly anyone’s guess how successful the OWS resurgence is going to be.

Hintze articulated some of the ideals that OWS tries to espouse through its everyday practices. “Things like direct democracy and mutual aid,” he said. “Things that subvert the system as it exists now; the system of representation in our government and the system of consumerism – where people can provide directly for each other, without contributing to that.”

Both Hintze and Davison noted heavily that it was necessary for Occupy to study and evolve over the past few months, so as not to fall victim to the very same power struggles as those who had drawn attention to the problem of economic inequality during the market crisis of 2007. The power bottlenecking that was seen in the actions of bankers, government officials, and police forces (in more recent days) is something Occupy has tried to keep a safe distance from.

“And it is hard,” Hintze said, “because the movement doesn’t have a public face now without that outdoor space.”

In this way, OWS was inspired to utilize more creative techniques and adapt super-localized decision-making structures. Without Zuccotti Park, organizers were practically forced to form more diligent and private working groups, although the tightly-knit network still remained.

Getting a dose more radical, Davison began comparing the behavior of stock market traders and government officials to that of a heroin addict, or a victim of a violently abusive relationship. The “1%” had to be given the space to accept that there is a problem, she said, or else they could never have the opportunity to realize that the chain must be broken.

The hope that lies within ongoing events of creative disobedience, strike training marches (held every Friday), and local teach-ins is that by the proposed day of escalation on May 1, a successful general strike can be held, ideally nationwide, with participation by all major cities and occupations.

***

It seems that Occupy is hoping to up the escalation to a level exceeding last fall in a much shorter amount of time, so as to grab the public’s attention in a more dramatic and meaningful way. Whereas the fall actions provided “culture jamming” that began to wear on the public’s tolerance, the May Day actions look to make a more productive use of time with a more diverse range outreach methods.

This is surely not a call to overthrow the government or any violent notion of the like, nor is it anything more than a climactic point of escalation for the movement, which hopes to represent and enact itself in a way that had not been seen in the fall incarnation. However, there are certainly standards of participation that need to be reached for May Day to truly be considered a revival or rebirth of the Occupy movement.

In time for May, OWS hopes to have “a General Assembly in every neighborhood in New York City,” according to Hintze.

Again, from an outside perspective — for the nightly news hawk or just your Average Joe — this whole idea might seem completely contrived. But there is a strong and influential history of successful general strikes held by anti-corporate and social rights groups. In addition to that, Occupy itself has held successful strikes, shutting down ports and protecting homes awaiting foreclosure. This action, of course, would be of an entirely different scale, and with an entirely different range of possibilities and reactions.

The presidential debates that have worn on over months and months have entertained the same political field which Hintze sees as anything but a “valid form of discourse,” and which Davison perceives as two parties both “incredibly conservative and owned by [the same] corporate interests.” That being said, it will be an ambitious task for Occupy to not only regain the public’s attention, but to directly influence the presidential debate through their actions.

What Occupy must be sure to do following the escalation of May 1 and leading up to the elections, it seems, is to problematize the general public’s relationship to representative voting. While the plans for next fall are not specific enough yet, they are looking to create a parallel spectacle that will show the public the fatal flaws of the two-party system in America.

It is not an interest of the movement’s to pursue representative politics, but it is obviously preferable for OWS and the “99%” to see change being made in the aftermath of escalating organization and direct actions. It would be counter-intuitive for a singular candidate to try and accurately represent a movement that takes pride in its practices of direct democracy, seen in the General Assemblies.

The direction that this vision begins to head in might seem reminiscent of, say, the direction of the Bolshevik Revolution, or the accomplishments of the general strikes of the Salt Marches initiated by Mahatma Gandhi, or the amendments won by the civil rights efforts of Martin Luther King, Jr., and many others.

As influential as those events may be on the minds of individual occupiers, they insist this is a different time, with more complex understandings and tools at hand that will undoubtedly shape how we as a global society progress to overcome the problems we face. The struggles that those historic movements have fought for are certainly sympathized by Occupiers — yet just as a historic event cannot be truly reproduced, the methods, tactics, and manifestos that drove them should not be attempted to be reproduced either.

Is there an end goal? Perhaps not one that can be talked about rationally at the moment. but that appears to be a natural part of the process, I suppose.

Davison put it bluntly. “I would like to see this be a movement that begins, and never ends. That, to me, is the end goal,” she said.

Hintze tried to maintain a sense of realism about the struggle that the Occupy movement faceS ahead. “To change everybody, to realize their place and the space that they take up in the world, and their personal relationship to other people and equality, that’s going to take a lifetime,” he said. Hintze noted that those involved must be open to change; that the movement is “both an emerging process, and something that sort of has a tacit end goal.”

The question that the public now ought to ask is this: Was the eviction, just maybe, the best thing that could have happened to OWS? Will the movement be able to pull itself back together in a more organized and fruitful way?

Occupy is calling out to all reaches of the country on May 1, from high school students to immigrant workers. Davison targeted university circles; “The New School needs an occupation,” she said. “I want all of the students, faculty, and staff involved, so let’s start talking about how to make this happen.”

“On May 1st,” Hintze added, “don’t go to school, don’t go to work, don’t buy anything, don’t do chores. Get in the street.”

Andrew Haveron is a third year student at Eugene Lange College, where he studies Social Inquiry

Leave a Reply