Goodbye Music, Hello Fro-Yo

Bleecker Bob’s record store is legendary to New York and music fanatics worldwide. For decades, vinyl enthusiasts made pilgrimages to the West Village landmark to trade, buy, and above all, learn about music. Jimmy Page once tended the register, and artists like David Bowie, Debbie Harry and The New York Dolls were regulars. Throughout its 45-year span, Bleecker Bob’s preserved historic bits of rock and roll in each poster draped against the shop’s walls.

Lawyer Bob Plotnik quit his practice to open Bleecker Bobʼs Golden Oldies in 1967 as a place to collect and sell his favorite records. Greenwich Village in the 1960s was prime for the burgeoning coffeehouse scene, home to folk artists like Bob Dylan, who paved the downtown cobbled streets with his poetry, guitar, and harmonica.

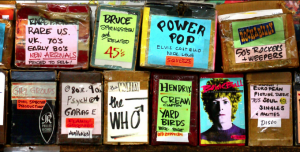

Bleecker Bob’s isn’t coffeehouse culture. Instead, paper versions of Johnny Thunders, The Clash and Joy Division line the walls, concert-Tee’s hang from the ceiling and vintage neon clocks lighten the shop.

The downtown New York record shop’s last location was between the Village Psychic and Ben’s Pizzeria, at 118 W. 3rd St. Most customers who entered the store didn’t seem interested in West 3rd Street’s new storefronts. They came to the block on a vinyl hunt. A message written inside the Bleecker Bob’s goodbye guest book relayed the customer’s general sentiment: “New York no longer deserves Bleecker Bob’s.”

On April 13, while Karla DeVito’s “Wake ‘Em Up in Tokyo” played in the background, Bleecker Bob’s sold their last record – the Ramones’ Road to Ruin. In June, Chicago-based frozen yogurt chain Forever Yogurt will take the space and open a franchise there. The frozen yogurt company strives for a distinct look at each location, one that “embraces the unique personality of each community,” according to the yogurt chain’s website.

Forever Yogurt proposed an in-store counter for Bleecker Bob’s to sell records, but the two companies could not work out space constraints. “I think [Bleecker Bob’s] wanted close to half the store, which was going to be really difficult,” said Mandy Calara, Franchise CEO of Forever Yogurt.

The rent at Bleecker Bob’s has fluctuated since the store’s opening. “We’re paying very cheap rent compared to what other people are paying for the same thing in this area, but it’s just too much for us,” said John DeSalvo, 63, an employee at Bleecker Bob’s since 1977. In 2001, after owner Bob Plotnik suffered a stroke and stopped working, DeSalvo became the unofficial headman at Bleecker Bob’s.

Employees are not the only ones suffering a loss. Lou Rosenthal, whose father, Al, has owned the West 3rd Street building since the 1970s, is sad to see Bleecker Bob’s go. “I love the store,” he said. “We’ve tried everything we could to keep them.”

Al Rosenthal kept a reasonable rent and worked with Bleecker Bob’s to help keep them open. But incoming chain stores continue to chase smaller shops from the Greenwich Village neighborhood.

Organizations like the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation strive to bring awareness to independent businesses in lower Manhattan areas. On February 25, the GVSHP co-sponsored a film screening with The New School for Public Engagement in honor of Bleecker Bob’s. The documentary film For the Records examined the plight of Bleecker Bob’s and the store’s role in the Greenwich Village community.

Andrew Berman, the organization’s executive director and native New Yorker from the Bronx, frequented Bleecker Bob’s as a teenager. He rummaged for New Order, Bauhaus, and Modern Lovers records in the same album stuffed milk crates at the store 30 years later. “There’s too few of these music stores anywhere. It really adds to the character of this as a creative neighborhood,” attested Berman.

All the community emotions, homages and fundraisers could not provide Bleecker Bob’s with a new lease. John DeSalvo, tired on a recent late-night weekend shift, said that numerous people offered to throw benefits in Bleecker Bob’s honor, but only a new location, not money, would save the store. “We can afford to move several places,” he said. “But nobody would let us do it. It’s all a matter of paperwork and financial records that I can’t get. What we need is somebody who knows a landlord over in the east side who will just let us move in.”

*****

Bleecker Bob’s was the first store in New York City to sell punk records. Owner Bob Plotnik, dark-browed and stocky, was known for his harsh attitude as much as his shop was known for its rare finds. Customers came to depend on the store’s specialty market although they weren’t always greeted with a smile. Plotnik was “slouchy and grouchy,” according to ex-rock critic and venue promoter Steve Weitzman. “Even though [Plotnik] was rude to most people, he always treated me well,” he said.

Weitzman, erratic and enthusiastic like the punk bands he promoted, met Plotnik in the mid ‘70s. “I loved going in there to see what was new so I could request promo copies from record companies,” he said.

Alan Antin drove an hour from Mancuso, New York to Bleecker Bob’s for the first time in over 20 years to show his son, Ben, the iconic place. “When you’re in a record store, you can flip through the records, and you can’t get the same feel of that when looking through iTunes,” he said “You can’t shrink artwork into iTunes covers.”

In Bleecker Bob’s prime, famous musician sightings were as standard as the weekly customers who test-played every purchase. “Once, Prince came in, and I said ‘What can I do for you, shorty?’ And he just stormed out!” recalled DeSalvo.

DeSalvo also remembered when Frank Zappa came in the shop prior to hosting a WPIX-FM radio show and asked for records to play on air. “I gave him some weird, off-the-wall records [including one by Gerry and the Holograms],” he said. “We sold out of those records in the next two days.”

*****

A few record stores still scatter the Village — Bleecker Street Records, Village Music World and Second Hand Rose’s Music, to name a few. Many are veiled under decaying canvas awnings, neglected by patrons and on the verge of closure with every free online song download.

Mark Hanford, visiting Bleecker Bob’s from England, says record store closures are a sad trend. “I’ve seen it happen all over London,” he said. “People want the immediacy of digital downloading. Everything about vinyl, for me, is about the artwork, about touching it. It’s about the physicality of it and these shops feed the need for people who feel like that.”

The convenience of digital music sharing and portable MP3s, introduced in the mid-1990s, have slashed record store profits worldwide. Rows of CDs lined the wall inside Bleecker Bob’s, a first sight and lure for the apprehensive vinyl purchasers.

Bleecker Bob’s sold their first CD in 1982, just after the move to their West 3rd Street location. Even with a modernized inventory, the store struggled to satisfy the demands of a fast-paced online market. “Five or seven years ago I was selling 75% CDs, 25% vinyl. Now its the other way around,” said DeSalvo.

Long time buyer Sandy Ehrlich seemed to sustain the store’s CD demand alone. “I don’t come all the time, but when I do, I buy a lot,” he said. Ehrlich chatted to other customers and paced the aisle as he, along with the whole store, listened as John DeSalvo test-played all 10 of Ehrlich’s CD purchases.

Although new technology posed potential sales issues in the 1990s, Bleecker Bob’s still profited. Owner Bob Plotnik made a 10-year deal with promoter Steve Weitzman to sell concert tickets out of Bleecker Bob’s for neighboring venues like The Village Underground and the now closed Tramps.

“Bob tacked on a $1 service charge,” said Weitzman. “It brought in extra revenue to the store every week, which Bob certainly appreciated.”

In the last decade, Bleecker Bob’s began to feel the effects of a declined and changing market. News of the store’s departure caused a boost in sales from the many customers purchasing their last albums from the store. “Now, of course, business is great, now that we’re closing,” stated DeSalvo with a chuckle.

*****

Despite spawning technology advancements in music, young music listeners are some of the top buyers of vinyl today. In the last three years, classic rock bands like The Velvet Underground and David Bowie — and jazz records from artists like Miles Davis — sold the most at Bleecker Bob’s. “They can’t get enough of that stuff, I’m just flabbergasted by it,” said DeSalvo. “I can’t even comprehend it anymore.”

Young high schoolers like 15 year old Jeffrey Bernholt, who came to Bleecker Bob’s every time he was in Greenwich Village, helped keep the store’s ambiance young. “I do shop at other record stores but [Bleecker Bob’s] really has the large collection,” added Bernholt.

As Bleecker Bob’s closes its doors, nearby merchants hope to keep New Yorker’s vinyl interests alive. Other Music, which once neighbored the now-defunct Tower Records, is a newer record store in Greenwich Village. The record shop, located at 15 E. 4th St., opened in 1995. The store caters to a youthful crowd of “men and women in their early 20s to late 50s with adventurous musical tastes,” Other Music co-owner Josh Madell told the *Free Press* in an email. The store’s peculiar selection of new and classic underground music continues to draw modern ears to explore Other Music.

Madell is confident in the future of vintage records, “I don’t think young people these days only listen to new artists,” he said. “There is a growing interest in music history in the digital era.”

Although sad to see their closure, Madell believes Bleecker Bob’s has seen better days. “These days, all [record] shops are in danger, but Bleecker Bob’s had not been a very good or relevant store for quite some time,” he said.

According to John DeSalvo, as many as 100 patrons visited Bleecker Bob’s daily in the store’s final year. Locals, regulars, and tourists sustained orders for the vinyl imports and posters that filled the store’s tight aisles and cluttered walls for so many years.

No new leases have been signed, but Bleecker Bob’s employees still search out possible storefronts to rent. DeSalvo remained hopeful as he organized the remaining records to be packed off into storage. “Maybe there will be a last minute reprieve,” he said. “I don’t know.” As friends, patrons, and employees celebrated the place they have long called home, Bleecker Bob’s waited until 5:15 a.m. — a reference to a song from The Who’s 1973 album, Quadrophenia — to lock up one final time.

With reporting by Tene Young and Charlotte Woods

Leave a Reply