The sidewalk outside of the Parsons School of Design is typically home to an array of stylishly-attired young designers, artists, and the occasional homeless wise man – but April 24 was a day out of the ordinary: the discerning fashion-conscious nonpareil caught each other wearing their clothes backwards, and not one called a faux pas.

Parsons’ Dress Practice Collective, a group that aims to challenge the ethical practices of fashion production, planned an event called “Fashion Revolution Day,” inviting people to turn their clothes inside out to spark a conversation about where their apparel is sourced, produced, by whom and in what conditions.

The event was held on April 24 to commemorate the one-year anniversary of the Rana Plaza factory in Dhaka, Bangladesh collapse, which killed 1,129 people and injured over 2,500 more. The incident was one of the worst industrial disasters in modern history – reminding much of the world that the days of coal mine cave-ins and massive factory fires were not so far out of sight, and sparked indignation from Bangladeshi workers demanding economic justice.

Photo By: Cayla O’Connell

Fashion Revolution Day at Parsons was part of an international campaign which was started by Cary Somers, creator of the fair trade clothing brand Pachacuti, with the goal of mobilizing western consumers to pressure the industry to improve working conditions in the textile industry, starting with awareness. “We want people talking about the provenance of clothes, raising awareness of the fact that we aren’t just purchasing a garment, but a whole chain of value and relationships,” Somers said in an interview in Vogue.

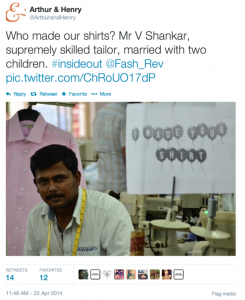

Organizers installed a photo booth at the corner of Fifth Avenue and 13th Street to take pictures of students wearing their clothes inside out. Those equipped with smartphones snapped photos using the hashtag #insideout on Twitter and Instagram to show off their backward-dressing statement – over 20,000 hashtags popped up around the world.

Parsons’ Dress Practice Collective is hopeful that events such as these will foster more economics-minded activism at the fashion-savvy school. “Fashion consumers are predominantly detached from the provenance of their garments, and the individuals behind the labels,” explained the group’s president Cayla O’Connell. “My hope is that through the heightened visibility of garment workers, factory conditions, and the production processes that enable the fashion system, consumers may understand their agency within its hierarchy and exercise better fashion practices.”

Similar consciousness-raising events were organized in over 250 cities. FashionRevolution.org provided the basic formula for those who wanted to get involved, as well as a toolkit for participants eager to arm themselves with facts, further reading, and ideas for action. Organizers encouraged groups to plan events in their area and spur people to reach out and pressure the brands they purchase to show commitment to a transparent supply chain by making public their materials sources and suppliers, and to connect consumers with producers and factory workers, encouraging them to “tell their story or have them tell their story,” as the website’s ‘Get Involved’ section reads.

“We felt that providing a base and platform for students to participate in the event through a photo booth on campus would not only signify our university’s support of the movement,” said Cayla O’Connell, president of the Dress Practice Collective. “But more importantly, we want to bring awareness to the ethical implications of the industry with which we all engage.”

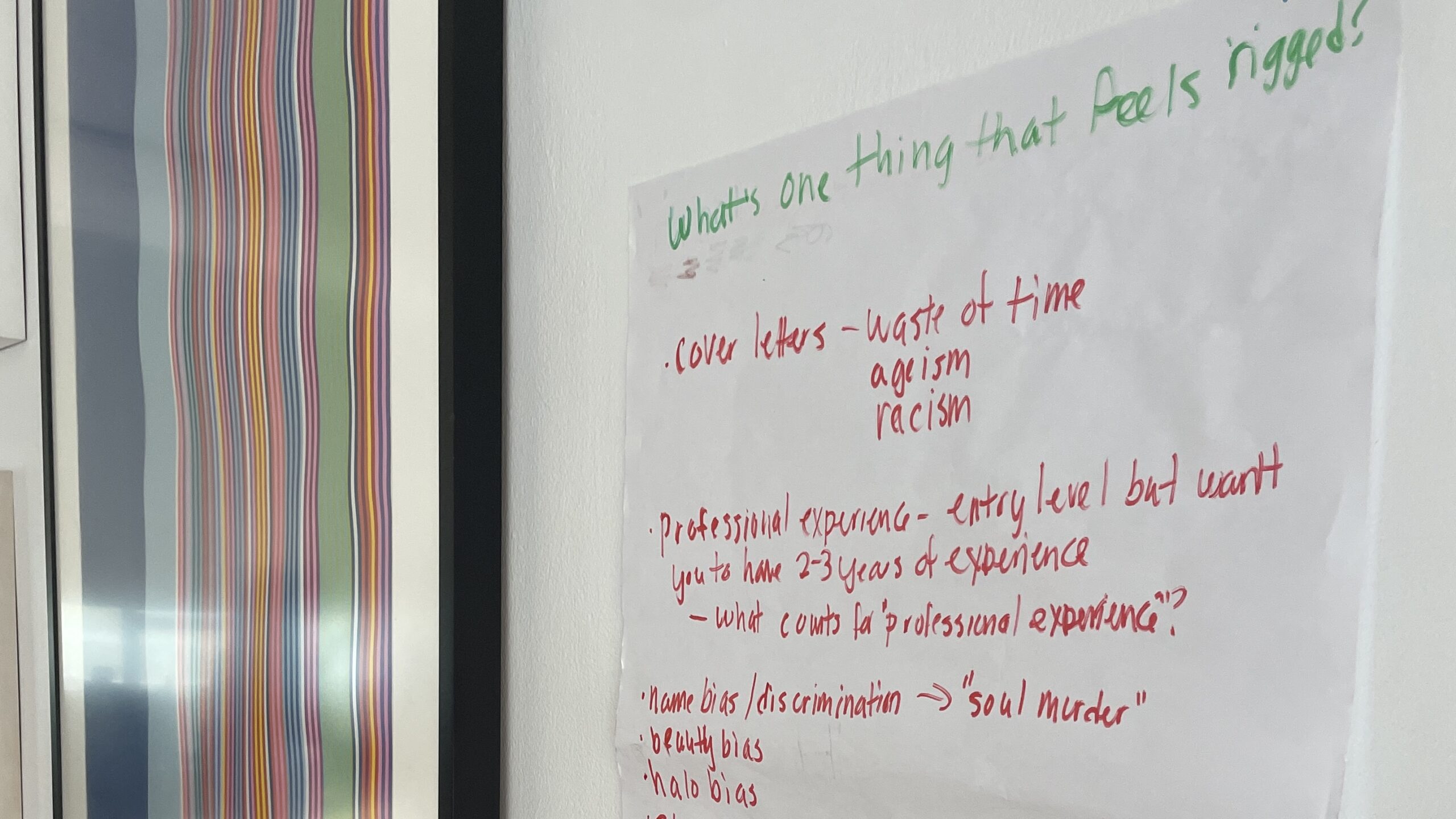

For some skeptics, taking Instagram photos of inside out clothes is not enough to effectively address exploitation in the globalized manufacturing industry. “While awareness is wonderful, it needs to be followed by action,” said Jens Astrup, a Parsons senior studying strategic design and management. “I’ve always believed more in attacking via regulatory or legal routes.” Other activists have decided to take on a more combative strategy.

While some activists buzzed on social media, others marked April 24 by forming a human chain of 1,129 people and blockaded a Gap retail store on Oxford Street in the heart of London’s shopping district. They called on Gap, and other multinational corporations to compensate families of the collapse victims in Dhaka, and agree to support labor rights reforms in the countries where their garments are produced, according to the Guardian.

Twitter: @LabourLabel

“There is simply no way that we can deal with the problems of the fashion industry by just shopping differently – they go way beyond that,” said fashion journalist Tansy Hoskins at an industry event in London. “We need to tackle them in a way that will actually terrify the capitalists in the fashion industry into changing things.”

Fashion Revolution Day partakes in a trend of elite fashion brands capitalizing on socially-conscious consumers. “The idea of challenging the system is surrendering interesting results – and also fashionable ones. Even the grandest of maisons are getting in on the action,” writes Alexander Fury, fashion editor at The Independent in London.

Lucy Collins, who teaches a course in Ethical Fashion at Parsons, poses the question more seriously: “How can we approach an industry that perpetuates overconsumption and has a severe impact on human rights issues in the disregard for the labor conditions in countries where these clothes are produced?”

Data from the International Monetary Fund rank Bangladesh as the world’s second largest textile producer, exporting $21.5 billion worth of garments in 2013 – before retail markup, which grossed $1.2 trillion in sales in the U.S. alone. A New York Times editorial in November 2013 cited Bangladesh’s surging 50 percent growth in industrial textile production, and a 28 percent rise in recent years’ prices, contrasted with practically unchanged wages. Trade unions fought bitterly against factory owners for better conditions and higher wages, which workers finally won when the country’s Labor Ministry raised the minimum wage 77 percent to ৳5,300 per month (about $68 in U.S. dollars).

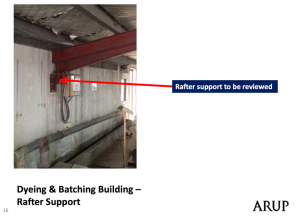

A report by Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology found 60 percent of 600 inspected garment factories to be structurally unsound and in need of repairs. The Spectrum Sweater factory in Dhaka killed 64 workers when it collapsed in April 2005. A fire in a textile factory claimed 289 lives in Karachi, Pakistan in September 2005. According to a report conducted by Human Rights Watch, workers claimed they had been subject to mistreatment, threats, and unreasonable punishment and termination.

Fashion Revolution Day intends to bring awareness of these issues to a consumer audience. Other schools around the world also came up with events that sought to help understand the severity of the working conditions in the sweatshops that produce their clothes. Regent’s University School of Fashion in London held an open screening of a documentary about the tragedy and an online charity auction that raised money for affected families. DePaul University in Chicago hosted a sustainability-themed fashion show to mark the anniversary of the collapse at Rana Plaza.

“I think that events such as Fashion Revolution Day and recent journalistic coverage of the problems with production are representative of the increasing need for transparency in the fashion industry” said Elizabeth Pulos, president of the Fashion Institute of Technology’s Corporate Social Responsibility Club, which also hosted a flea market of ethically sourced and fair trade clothing, and engaged with students and professors about who made their clothes.

Professor Collins proposes that the next question remains unanswered:

“You need to sell clothes – but how do you do it in a way that isn’t weighed down by consumerism and excessive glamour, and has a care and concern for both the people who manufacture the clothes and the people who wear the clothes?”

Shawn is a native of Queens majoring in Politics at The New School. He joined The Free Press in Fall 2013, and covers student life, academic affairs and activism on campus, bringing a critical investigative approach to journalism through social media, institutional research, and data-driven fact finding.

Shawn’s work has appeared in Adbusters, The Nation, PolicyMic, Truthout, The Brooklyn Indypendent, and the Italian news magazine, Internazionale. He is also a research and analyst for the government and corporate transparency project, LittleSis.

Shawn likes only five things: black coffee, unfiltered cigarettes, smoky whiskey, dark Belgian beer, and the news. He speaks five languages and loves to travel. Shawn shares a birthday, April 4th, with Grumpy Cat.

Leave a Reply