Hundreds of New York college students turned from Union Square onto Fifth Avenue chanting, “We are the 99 percent” as they made their way toward a larger Occupy Wall Street gathering in Foley Square on Nov. 17, 2011.

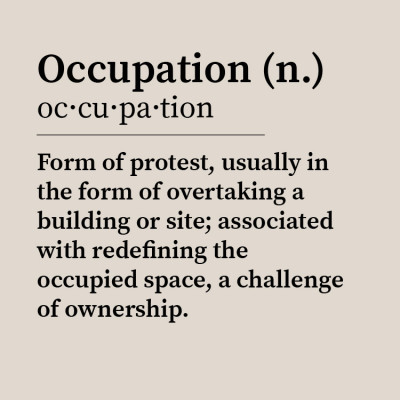

But the mass of people halted at 14th Street and suddenly, a group of students bolted for 90 Fifth Ave. and up to the New School’s Student Center on the second floor, beginning again, with a flash of action and confusion, the university’s third occupation in four years.

This was their time to take what they felt had been robbed.

The occupation of 90 Fifth Ave. would end on Nov. 25, and be, to date, the last of its kind. The 2011 occupation was reminiscent of the previous 2008 occupation at 65 Fifth Ave., but with David Van Zandt as president, The New School handled the occupation with patience and negotiation, careful to avoid violence.

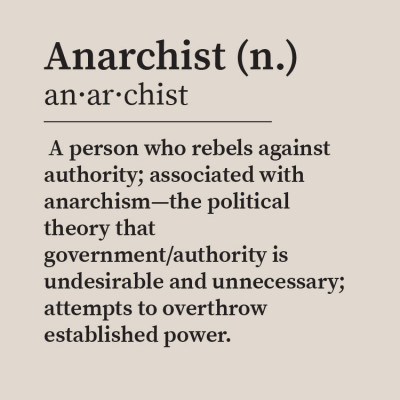

Attracting more than just New School communities, students of surrounding colleges attended the New School occupation, hoping to find a space where open political discussion would take place. Many of the occupiers were marginalized by a group of students who practiced a radical interpretation of anarchism. Despite planning on the part of students, the occupation at 90 Fifth Ave. deteriorated when the students graffitied the walls, in turn breaking The New School’s lease with the owner of the building.

The failure of the New School occupation created a stigma around occupations, which is in part why the New School hasn’t seen one since.

“[That] led to a decline in that earlier type of activism,” Jim Miller, a Professor of Politics at the New School, said. “Whereas, the students who were involved in social justice issues, they came out of this playing a much more prominent role.”

It also changed the way people at the university took political action, according to Joe Giacona, who attended the occupation as a Lang freshman.

“I think that activism at the New School has gotten better in the way that people are organizing and talking rather than showing because the anarchists were really about showing and not talking,” Giacona said.

Occupy Wall Street, the global movement which began with the occupation of Zuccotti Park on Sept. 17, two months prior to the student occupation, was a heavy influence in the occupation of 90 Fifth Ave.

“Occupy shifted the political climate across the country. It brought thousands of young people into the movement,” said Yotam Marom, a New School alumni who was involved in the planning of some of Occupy Wall Street’s impactful moments. Occupy Wall Street inspired community action as students at The New School and other universities throughout the city prepared for change.

Around this time, a small group of students started holding meetings to plan some sort of political action, according to Occupy Wall Street activist and New School for Social Research student Cecily McMillan.

“Moving forward, I got the information that the meetings were going to be closed meetings and invite only for the technical planning of, ‘something big,’” McMillan said. New School students met in the Lang courtyard for an open meeting before the occupation to map out their motives and develop a plan for how the group was to advance, according to McMillan.

McMillan had distinguished herself with her adamant stance for non-violence during the sometimes volatile Occupy Wall Street demonstrations downtown. Knowing this, her professor, Jim Miller, encouraged her to attend the students’ meetings, McMillan said.

New School students seized the opportunity to occupy 90 Fifth Ave. during the All Students March in solidarity with Occupy Wall Street on Nov. 17. The New School occupation was seen as a part of Occupy Wall Street.

Once inside 90 Fifth Ave., all seemed to be going well. Students had flocked from their classes and into the building to take a stand on issues like tuition, financial aid and privatization, according to McMillan. New School administrators were were generally supportive of the protest. Van Zandt even held open doors for students.

“We chose to allow protesters to be in the space because we wanted to avoid a scenario resulting in force, violence, or personal physical harm to anyone,” Van Zandt recently told the Free Press.

Despite this initial support, the occupation dissipated after just over a week on Nov. 25. “You had the best activists from every school. They could’ve come together. They could’ve come up with demands for all schools across NYC and that could’ve been it,” McMillan said. “It really could’ve been a national student movement. With the activists that we had there, it could’ve been something amazing.”

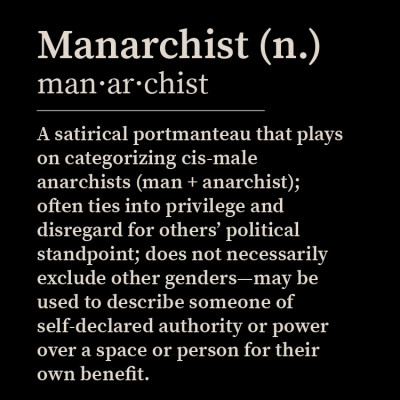

In what would be the first of a complex set of problems which ushered the failure of the occupation, the leaders of the New School occupation, often derisively referred to as the New School Manarchists –so named because they tended to be young men– broke from the nonviolent tradition of Occupy Wall Street. They refused to give a statement of non-violence, which McMillan initially proposed.

“It seemed very clearly to be headed towards some kind of occupation. It was just that time–that spirit of taking back and the method of taking back was occupation,” McMillan said. McMillan’s agenda for nonviolence was not well received within the core group of planners, especially by the then Eugene Lang student, Gerald Koch.

“I’m very uncomfortable with anyone speaking for this group, or any group, without all of our permission, to say that we are violent or nonviolent or anything else,” Koch told the Free Press in 2011.

Koch and the other leaders of the occupation of 90 Fifth Ave. have since declined to comment despite multiple attempts at contact.

The anarchists refused to be covered by press, which stood in stark contrast to the bigger occupation downtown which was far more welcoming to reporters, according to the 2011 Arts & Culture editor of the Free Press, Andrea Vocos. From the first day of the New School occupation, a ban was set on photography and all press was barred from the building. Occupiers taped up an image of Aidan Gardiner, a New School Free Press alumnus who was covering the occupation for The New York Times, with the words ‘Persona Non Grata,’ written across his face.

Though the New School occupation was spurred by Occupy Wall Street, the all-inclusive, open nature of the event seemed to stay on Wall Street. The anarchists still decline public attention four years later.

“The concept of not allowing the press in seems counterintuitive” said Vocos, who managed to make her way into the occupied building and snap a photo of Van Zandt addressing students.

“The largest [problem] that I had with the occupation in 2011 was that in the earlier occupation, they were asking for a 24-hour student center, and now they were kicking kids out [of the student center]. It seemed misguided,” Vocos said. A lot of New School students held issue with this. Students in the past occupied 65 Fifth Ave. in 2008, in an attempt to gain access to a public space for those who attend The New School. This space was later granted as 90 Fifth Ave.

“One of the demands that was made was that a student study center be created,” Miller said, “the space that was occupied in 2011 was itself created in response to the earlier student occupation [in 2008].”

The dynamic among the occupiers proved the most detrimental aspect of the occupation.

According to Miller, during the New School occupation a group of students of color raised questions about the lack of inclusivity within the occupied space. “[They] very quickly said, ‘Wait a minute how come this is a total radical, white space and there’s no people of color here’ and that created splits,” Miller said, “It was pretty easy to drive wrenches into a student occupation with a leadership that was not particularly skilled in knowing how to sustain what was going on.”

“I think that the big problem was that you had some irreconcilable political differences within the different groups there,” said Chris Crews, current graduate student at NSSR, who was an active participant as a member of the New School’s Social Justice Committee at the time of the occupation.

After day one, it became clear that the group of New School anarchists, bound by their similar political views, fought for control over the occupation, according to McMillan.

“It wasn’t politically segregated as if there was a bifurcation, there was just in or out. It wasn’t liberals versus anarchists, it was, ‘This is an anarchist space and if you’re liberal, get out,’” Giacona said.

McMillan described a moment in which CUNY and some SUNY students held a “vote of no confidence” and walked out of the occupation as a group, after it was made clear that “identity politics,” such as politics of race, gender, ability and sexual preference, were not welcome within the occupied space. “If you delegitimize the voice of your student population in The New School when it’s a citywide occupation at The New School, you’re going to bottom out the foundation,” McMillan said.

According to McMillan, the New School students who led the occupation, “don’t know how to work with other people, they don’t know how to collaborate, they don’t know how to inspire people.”

McMillan noted that it is easy to find fault in the tactics taken by the anarchists but said, “I can also see why they got to be the way that they were. I don’t think that excuses it, but I do think that when you have your knee on the back of somebody and you’re digging and digging and digging, they’re going to react.” However polarizing the anarchist’s views were, she noted that, “without them, there would have been no occupation to begin with.”

Towards the end of the occupation, the number of occupiers dwindled. By Nov. 22, the occupiers had trashed the student center with graffiti to the extent that the owners threatened legal action. The administration proposed a new space to occupy, the Kellen gallery in the Parsons building.

The proposal of a new space further aggravated the internal issues. While many of the remaining occupiers agreed to move the occupation, the anarchists refused and issued a final statement before quietly disappearing from the Student Study Center on Nov. 25.

Once 90 Fifth Ave. was vacant, university staff discovered that the second floor was covered in graffiti, trash and clouded in cigarette smoke, all of which violated the school’s lease agreement. The Kellen Gallery was also vandalized, resulting in $40,000 of damage.

Most of the students who were involved in the leadership of the occupation have since graduated. “The grad student leadership of these occupations fell apart after 2011, it took a while, but it fell apart,” Miller said. “People who had been very involved came to feel that they had been set up and some of them began to feel that they’d done foolish things.”

“Something that whole experience taught, not just with [the anarchists] but with the Occupy Wall Street movement in general, is that you need to include [all] people because their struggles are a big part of what you’re talking about,” Giacona said. As a result, he said the people who felt marginalized “really came to the forefront” after the occupation of 90 Fifth Ave.

Check out our full Activist Dictionary here.

Check out our full Activist Dictionary here.Giacona described the politics in The New School now as, “less spectacular, but more organized.”

Today, identity politics play a large role in our in class discussions, as well is in the types of protests and demonstrations that we see around the New School and around New York City.

The end of the New School’s Occupy era left a void in activism at the school. “The activism at the New school that I’ve seen has been headlined by people of color. Women and queer people filled that void.”

“You still have activists,” Miller said, “Their politics are just different.”

All graphics by Marissa Baca.