When walking through the fashion studios on the fourth and fifth floors of University Center, one will find students — mostly dressed in all black — hunched over large work tables cutting fabric or draping material on dress forms. Piles of fabric scraps, threads, and pattern paper litter the floor, while the hum of Juki sewing machines creates an eerie soundtrack to the robotic, almost zombie-like movements of the sleep deprived design students. When the studio door opens, their dark circled eyes light up to the sight of Marco Viteri, the head sewing machine technician and arguably, the most popular person at Parsons School of Fashion.

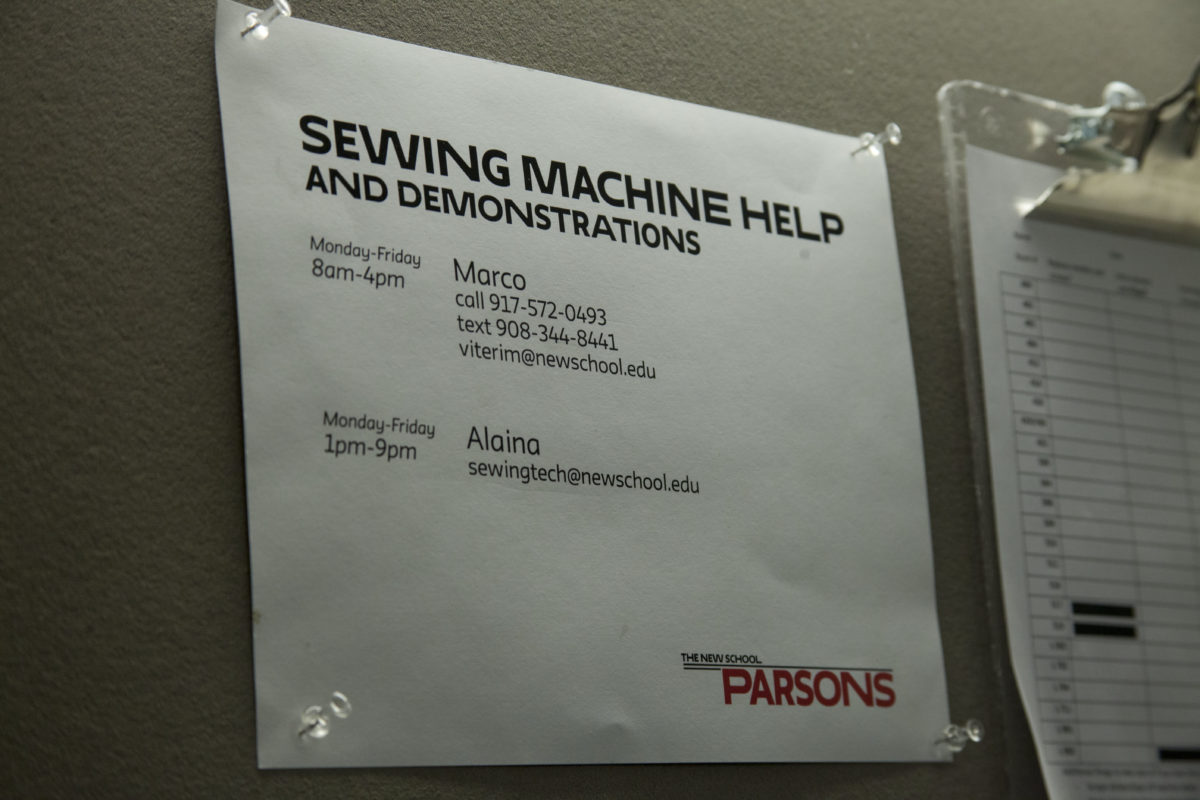

Viteri, a 57-year-old man from Ecuador, is not the person you’d expect to have a cellphone and Facebook constantly blowing up with texts from college-age fashionistas. Instead of being bothered by the nonstop ringing, he lists his phone number on the wall of every studio. When he gets a phone call at 2 a.m., he answers and explains to his wife next to him that it’s just a Parsons student asking how to sew a French seam or make a welt pocket. When Viteri makes his way through campus — in a black leather jacket he made himself — he is constantly stopped by students who he hugs and asks, “How are you, sweetie?”

“He’s the only person who can get away with calling you sweetie when you’re stressed,” said Rocky de Castro, an AAS Fashion Design student. Like many students, de Castro said his constant smiling, extreme helpfulness, and sense of humor have endeared him to class after class of fashion hopefuls. “When you’re under high stress, you actually want to see him,” she said. “He always has the answer to your question.”

Viteri has worked at Parsons for 7 years and despite the post-midnight phone calls and constant student questions, he considers his job to be “paradise” compared to his previous workplaces.

Viteri moved to the United States when he was 21-years-old with a visa purchased with money he earned in Ecuador’s army and a plane ticket bought with a loan. He first came to Hoboken, New Jersey, where his uncle lived. His uncle explained that there were not many jobs available for an industrial metal mechanic, Viteri’s original profession, in this country. However, in 1981, Hoboken was full of garment and textile factories.

Viteri arrived to the United States on a Saturday night. His uncle began teaching him how to use an industrial sewing machine the next day. That Monday at “seven in the morning,” Viteri went factory to factory, knocking on doors and asking for work.

After several weeks of rejections, Viteri’s uncle advised him to tell factory supervisors that he had experience in the industry when they asked. After telling one factory manager that he could do “whatever,” Viteri was assigned the task of attaching sleeves to linings of jackets. He completed only one — with the sleeves on backwards — in a half hour and was sent home, “almost crying.”

“[The manager] told me, ‘Do me a favor. Get off the machine and get out of this place because I don’t want the owner to kick your’ — pardon my language — ‘ass,’” he said. From that experience, Viteri said he learned that it was never good to lie.

Finally, one factory owner hired Viteri when he came knocking at the company’s door, “hungry for work.” In 2 years, he taught Viteri everything, from beginning to end, in garment production.

“If you teach me, no problem. Just give me a chance. Show me whatever you want and I will learn,” Viteri said to his boss.

In the span of nearly 30 years, Viteri learned to make women’s, men’s, and children’s clothing, homeware, and even leather bikinis for Harley Davidson. He got a certification to fix the industrial machines and worked his way up, through several companies and many periods of lay-offs, from ironing open seams to becoming a machine technician to the head supervisor to a production plan manager overseas in Egypt. He said he helped a $5 million company grow to $40 million company and a $60 million company grow to over a $100 million company. At his very first job granted after going door to door, Viteri was making around $2.75 an hour. Later on, at one point, he was offered a position that paid a salary of $100,000 per year plus a new car and a down payment on his house. However, he rejected this offer, as it was across enemy lines; the owner of this company was the former salesman of his boss at his current company. Taking it would go against his conscience and even going in to talk with “the enemy” made Viteri feel like he cheated his boss. “I felt so bad. I cried in front of my wife and said ‘honey, this is not good,’” he said.

This boss, the best boss that Viteri said he ever had, was at a company in Newark, New Jersey, called Rainbow Looms. After helping to increase production and profit in just six months, his boss called him to the office and placed a brown paper bag on the table. Viteri thought it was bread, but his boss pulled out a wad of bills, $10,000, as a bonus for his good work.

As he recounted this moment, Viteri’s eyes welled up. “He was the best boss I had, the best. You don’t find a boss like him. Not here, not anywhere.”

When many international trade barriers were reduced and eliminated in the late ‘90s, garment factories and production moved overseas. Viteri had trouble finding work in the U.S. and went on unemployment, but the money was not enough to support him and his five children.

“I thought ‘Oh my god, I got my two kids — actually total, I got five. I don’t know what to do,’” he said. “I [was] worried about all those things.”

After some time unemployed, he found a job listing for a sewing machine technician at Parsons the New School for Design. However, the job paid significantly less than his previous positions and Viteri originally denied the offer.

Viteri said that when he turned down the position, the Parsons professors who had interviewed him asked, “Do you know that this school is the most famous [fashion school] in the world?” to which he replied, “I don’t know and I don’t care. If you don’t pay me the money I need, then I don’t work, no matter if it’s the best of the best. I’m sorry.”

Fortunately, after negotiating the starting salary, — Viteri had almost 30 years of experience in the textile industry at that point — he accepted the offer. “On December 14, 2009, 9 a.m. in the morning, I started working at Parsons,” he said.

Viteri said that his time at Parsons has been “the best experience in his life” because he gets to work with students. He admits, however, that sometimes, the administration “hates” him because he tells them that it is not the school who pays his salary, but the students who pay his and theirs.

As for the students, they love him. “Everywhere I go, [students say] ‘Hi Marco!’ and they give me hugs; they give me kiss; they love me, even the teachers.”

“Ah, I love Maro,” Irene Lu, a junior in Fashion Design said. “He’s so warm and friendly, even if he doesn’t know your name. He has a good sense of humor too.”

Faculty members feel similarly grateful toward the beloved sewing machine technician. “At the start of a new semester I always tell my students how fortunate we are to have Marco in our school. He has had a great impact on keeping our machines and irons in great working order and teaching both faculty and students the intricate workings of many specialty machines on premise,” said Genevieve Jezick, a Fashion Design professor who has taught at Parsons for more than 13 years. “He is always happy to see what my students or I are creating and to answer any question we might have.”

Ann Stone, a junior in Fashion Design, competed in Fusion Fashion Show, the annual fashion competition between Parsons and the Fashion Institute of Technology, last year. Over winter break, while working at home on her Fusion collection, she “had a meltdown in Missouri. My [sewing] machine wasn’t working, so I emailed Marco. In three days, he shipped an industrial machine to my house — a fully built industrial machine to Missouri in three days.”

His dedication to students extends past his duties as a New School employee. “The school never pays me after 40 hours and every week, as soon as the semester started, [I’ve worked] at least 2 hours per week overtime, … but I never ask [for compensation] because they never pay me and I don’t care, I care about you guys. If you need the help, not a problem,” he said.

The New School follows the federal Fair Labor Standards Act which states that exempt employees, like Viteri, are “employees who are not required to be paid overtime, in accordance with applicable federal wage and hour laws, for work performed beyond 40 hours in a workweek… Exempt employees are expected to stay as long as necessary to complete assigned tasks, notwithstanding the absence of any entitlement to overtime pay,” according to the school’s website.

When asked what his family thinks about 2 a.m. phone calls from students and unpaid overtime, Viteri said they understand because he has a 7-year-old daughter who follows him everywhere and is his “tail.” She sews on her very own machine in her father’s studio and when he sings, she sings along. (Viteri once was the lead singer of his own Latin music band that performed at events for Anheuser Busch, the brewing company which produces Budweiser.)

He hopes that when she is in school “that someone helps her like I try to do with you guys. I think that somebody in the world [has] got to do the same thing, so that’s the reason.”

Photos by Julia Himmel.

Allie is the News Editor for the Free Press. She is a super senior finishing her fifth year as a Journalism & Design student at Lang and a Fashion Design student at Parsons. She also covers local news for the Staten Island Advance and writes about issues within the fashion industry for a not-for-profit online publication. A native New Yorker, Allie now calls Brooklyn home, where she resides with an orange cat and a pint of coffee ice cream hidden in her freezer at all times.