The exhausted 17-year old sat alone, only accompanied by four meat-packed plastic bags aboard a train for her 30-minute commute back home to the South Bronx. From the meat market in East Harlem, the round trip took more than an hour, not including the walk from the train station to her home, while carrying her bags: “It was terrible.” In addition, the subway fare, travel time, cost of the fresh meat, and her tiredness were all just apart of “the hardship that comes with it, to just eat food.”

Such a vital, strenuous journey was not uncommon for her, but it had to be taken for the privilege of fresh food.

Ariadne Vazquez, now 21, found herself living in the heart of a food apartheid, which is more commonly known as a food desert—a Band-Aid term that glosses over the myriad of issues that accompany racial and economic disparities.

Vazquez’s neighborhood wasn’t entirely devoid of food, but substantial, healthy food was absent.

Vazquez didn’t have the option of taking a cab to the local store. Distance is a significant inconvenience in low income neighborhoods, and the hassle of taking a bus or train is not always cost effective, according to Vazquez. For others, grocery shopping is an annoying chore that gets done only because it has to. For some it’s not a feasible option for getting food and is not matter of choice.

“It’s just the hardship that comes with it, to just eat food.” -Ari Vazquez, 21.

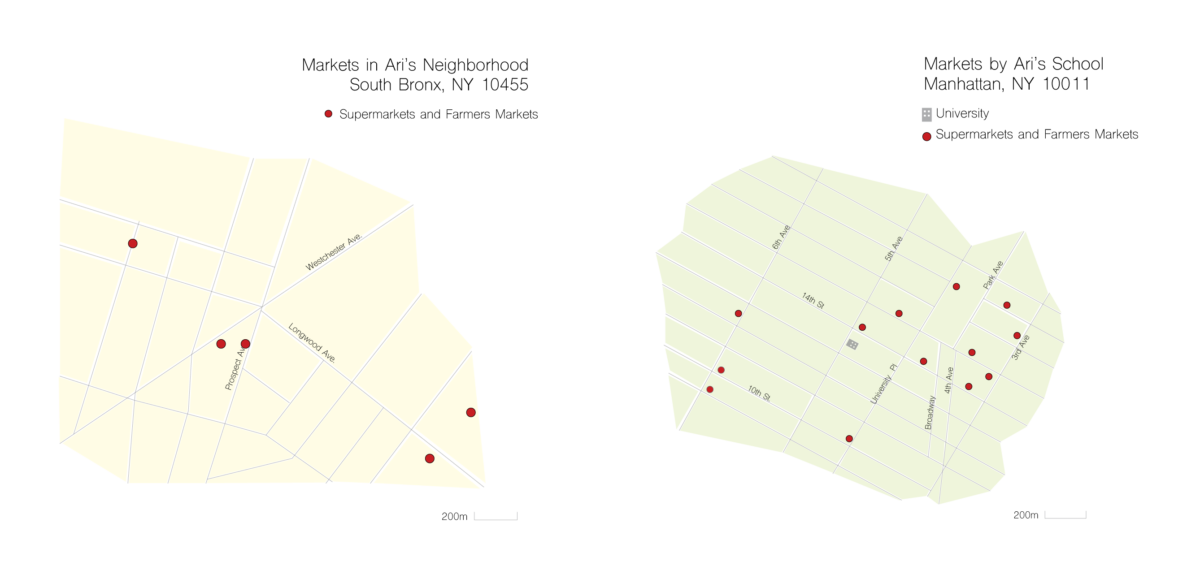

She and her mother lived in the South Bronx for six months, where their everyday realities were filled with hardships. The low income housing the two lived in suffered a rat infestation, intensifying her mother’s phobia of rats. As a result, they had to buy a limited amount of food at a time. All that was kept was pandulce (sweet Mexican bread), tostones, platanos, and sometimes fish and vegetables from the Longwood Fish Market, which is “probably the healthiest food in that neighborhood,” according to Vasquez.

“But, in the building I lived [in], everyone went through the same struggles… so we tried to have each other’s backs,” she recalls the time when her neighbor received her food stamps before her mom, and their neighbor cooked enchiladas for them when they didn’t have dinner.

“Seriously there were days of just hunger.”

Consequently, Vazquez began to feel the health complications that come with lack of food: “I wasn’t working, and seriously there were days of just hunger.” After visiting a doctor, she realized she was malnourished. Because she didn’t have a source of income, she was faced with the harsh reality of hunger: “It’s just, you can’t buy food, it’s just difficult.”

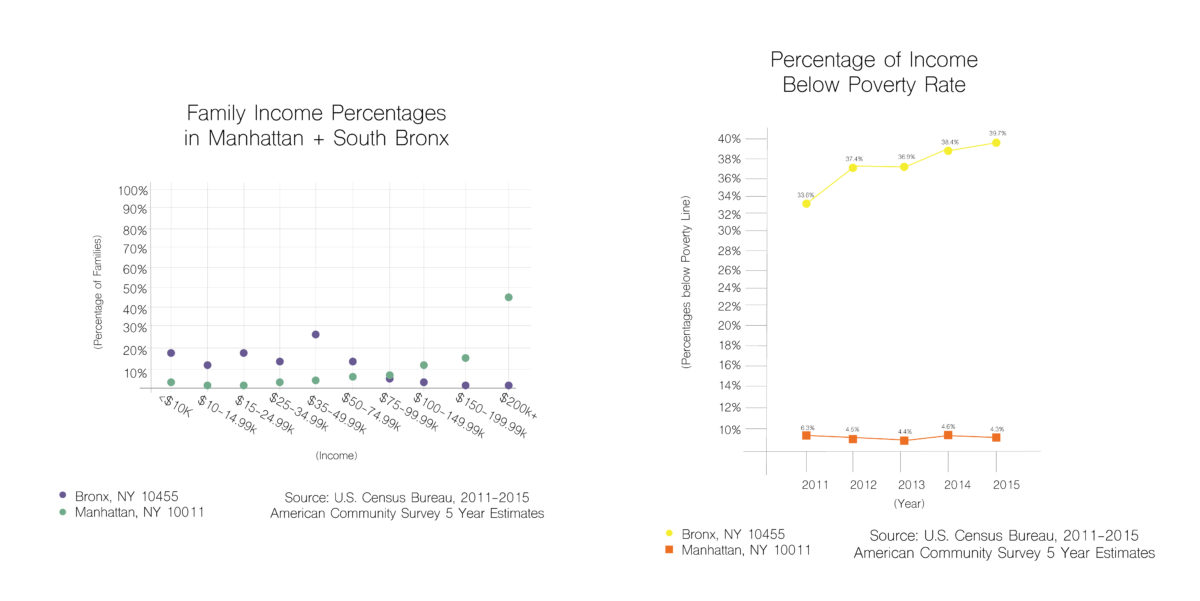

In the South Bronx (District 17), the median household income averaged at $23,253 in 2015, according to the U.S. census. Just 15 miles south on New School’s campus where Vazquez now attends classes, the median household income averaged at $109,818—nearly eight times as more as the median household income of some South Bronx residents.

Vazquez explains the credit system at bodegas: if one does their shopping but cannot afford to pay up front for their foods, they pay the clerk back upon receiving their food stamps. Bodegas are the central piece to getting their groceries because of their convenience and affordability. According to Vasquez, they even sometimes allow people to pay everything in food stamps.

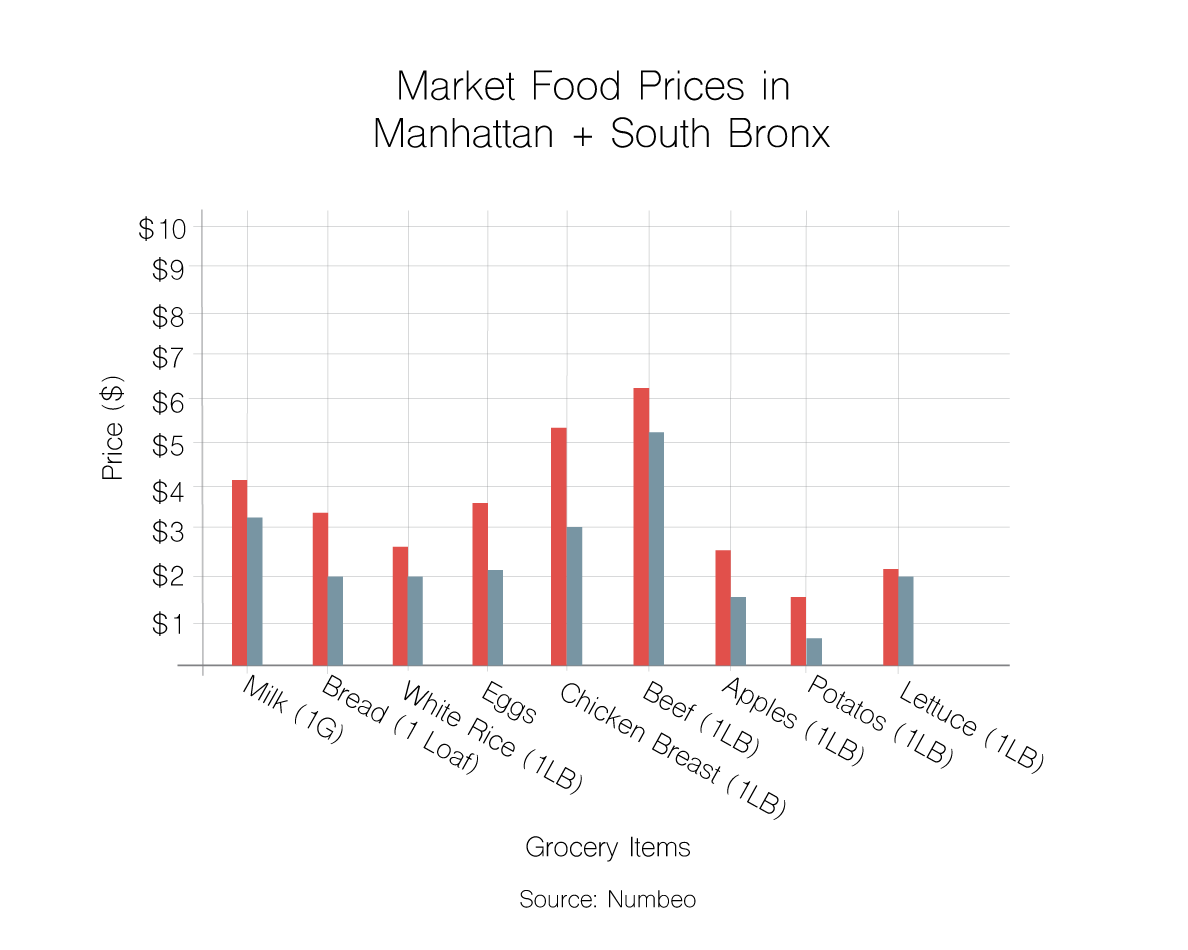

Vazquez explains that a meal large enough to feed a family—tostones and fish—would cost about $8. But such a diet becomes expensive when one lives in a food apartheid, as it would cost $56 to feed a family that same meal for a week straight. This doesn’t include purchasing other necessities such as toilet paper and toothpaste.

Meals for that price in The New School area exist, but it’s arduous to find a dinner at such a price. Quick meals like $1 pizza, or a bowl of soup or a sandwich from Westside Market only last for an hour or two before one’s hunger starts up again. They do not warrant leftovers. Such small meals are within budget, but with nothing else to accompany them.

These inequalities exist in a seemingly quiet manner, yet become more and more insidious each day—so why does hunger exist? Perhaps it is because there’s limited access to healthy eating. A seemingly obvious solution would be to simply place a grocery store to make accessibility easier, but that isn’t the case.

“We tell people, we do have food. What we don’t have is access to healthy food.” -Karen Washington

According to a study conducted by NYU in 2013, building grocery stores in areas affected by food apartheid is not an effective solution. Socioeconomic conditions as well as people’s shopping and eating habits take part. Pam Hess, one of the panelist in the NYU study and executive director of Arcadia Center for Sustainable Food & Agriculture, speaks on the eating habits of people in low access neighborhoods. “The backwards notion that I was talking about is that because convenience foods…have been the only thing available, that’s what folks have eaten. So anyone looking at that neighborhood would say ‘These people don’t want us here.’” Farmer’s Markets don’t want to spend their time in these neighborhoods, because they believe that people who are used to eating a certain way, as it was the only way to sustain themselves, may be reluctant to transition into an unfamiliar diet. Another layer to the issue is the cost difference of using food stamps at a bodega versus a grocery store. As Vazquez mentioned, you get more bang for your buck at bodegas because the owners are flexible with the way you can pay for your food. It’s the more feasible option. While adding the healthy grocery store to the area can eliminate the travel costs, it still does not necessarily make buying healthier foods any easier.

The solution to hunger thriving in a food apartheid is complex, as racial, class, equity, and other factors contribute to such a question. Karen Washington has been striving to answer that question for more than 20 years. The urban farmer has been growing her own food in “The Garden of Happiness”, which she started just three years after moving to the Bronx in 1985. She is also an active member of Rise and Root Farm, and La Familia Verde Farmer’s Market in the Bronx, and five community gardens (including “The Garden of Happiness”).

Washington has been a catalyst for not only healthy eating and farming, but as an advocate and activist. She travels around the country and discusses social justice from a race and equity standpoint.

Washington doesn’t use the term “food desert” as it is an outsider term that implies low income neighborhoods are devoid of food. “We tell people, we do have food. What we don’t have is access to healthy food. So instead of calling it a food desert, we like to use the term ‘food apartheid.’”

In a piece published on CenterforJournalism.org, titled “Covering Food Deserts,” Christopher Cook, author of “Diet for a Dead Planet: Big Business and the Coming Food Crisis,” referenced food justice advocate Hank Herrera who is also the President and CEO of the Popular Research, Education & Policy (C-PREP). Herrera explained the controversy of the term food desert in Cook’s piece. “That lack access to fresh, healthy, affordable food results from structural inequities, deliberate public and private resource allocation decisions that exclude healthy food from those communities…The desert metaphor only diverts attention from the inequitable, unjust condition.”

Food apartheids do not happen overnight. They are a result of systemic racial and economic disparities, specifically targeting low-income people of color. When looking at nearby locations from Vazquez’s home, this reality is clear. Bodegas are abundant and healthy food options are absent in these neighborhoods. For example, in 2014 the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene collected data about food environments in the Crotona-Tremont (zip codes 10453, 10457, and 10460) areas of the South Bronx.

Out of 571 establishments, 46 percent of the businesses were bodegas and 19 percent were fast food restaurants. More than half of the bodegas readily advertised unhealthy eating options through displays and their checkouts, making poor options such as sugary drinks and unhealthy snacks highly accessible to their residents. Based on the information from the U.S. census, 66 percent of the population in the area were Hispanic, with 38 percent earning an income lower than the federal poverty level.

Nonetheless, the question should not be ‘what are people who are affected by this doing to resolve the issue’. Rather, it is about hunger, and why hunger thrives in food apartheids.

Initiatives have been taken by Bronx council members, Ritchie Torres and Rafael Salamanca Jr. Torres, a Democratic council member for District 15 of the Central Bronx, allocated $10,000 in 2015 to HealthBucks, an organization that promotes healthy eating and living at an affordable price. As a result of HealthBucks, shoppers can pay for their fresh fruit and vegetables at Farmer’s Markets with their food stamps. Salamanca Jr., Vazquez’s council member for District 17 of the South Bronx has made some changes within the community. According to Catholiccharitiesny.org, he donated $10,000 to local Catholic charities to help with their Food Hub startup. This program provides up to 80,000 meals per month to all Bronx residents and upper Manhattan. Options available include local community gardens striving to make changes, council members allocating funds towards healthy eating, and organizations such as Bronx Green-Up partnering with the Bronx Zoo to provide healthy options to Bronx residents.

Though there are solutions, that does not mean the issue of hunger will be solved overnight. “(We) eventually did leave that neighborhood though…But, personally it did affect me…and I just don’t want to go there because there’s nothing there anyways.” Vasquez admitted that there has been no change in the old neighborhood she used to live in. These things take time and tremendous effort on both sides to make change. Reaching out to your district’s council member to learn more about food and health policies within your neighborhood are vital to ignite change. Find your district and learn more about your council members here, and contact them with questions or concerns about the status of your neighborhood. Food apartheids are unnatural, and instead of proposing temporary solutions, it is more about asking, why does hunger exist?