The election of President Trump sent millions of people around the world to the streets to protest. With them came the dusting off of the political chant as a catalyst for change.

“[Chants] can be important articulations of the values and demands of a community that captures the spirit and the content of resistance and speaks powerfully to the moment,” New School history professor Jeremy Varon explained.

Varon teaches a class at the university called “Peace to the Poets: Using Spoken Word and Music to Change the World and Yourself” in partnership with the political artist collective, The Peace Poets, who use poetry and spoken word as a way of dealing with and raising awareness on complex political issues. The Peace Poets are responsible for the Black Lives Matter anthem “I Still Hear My Brother Singing,” which went viral in December 2014 in response to the killing of Eric Garner. The course not only examines the historical aspects of the political song, but also its place in the contemporary resistance.

“Musical cultures remain important reservoirs for the development of peoples oppositional politics and even radicalism, but we don’t tend to be producing protest anthems in the way we once were,” Varon said. “The peace poets are out to change that.”

The crew of five men have taken up the role of the politically charged protest artists of the later part of the 19th century, Varon said. He is, of course, talking about the Bob Dylans, Sam Cookes, Phil Oaches of the early ‘60s and ‘70s to the hip-hop artists of the late ‘80s, early ‘90s, N.W.A, Public Enemy, Tupac, Biggie and A Tribe Called Quest.

“Being political is clearly in,” Varon said, “and that’s generally a good thing.”

There is a widening sense that people in the public eye are obligated to use their position to speak out against political injustice, according to Varon. Artists like Solange, Chance the Rapper and Kedrick Lamar have taken up where Grandmaster Flash left off. They have taken a stance against police brutality and injustice against the black community, experts said.

Jamey Jesperson, political organizer, protester and New School graduate points to Beyonce’s visual album “Lemonade” as an example.

“If you look at Beyoncés whole visual album of Lemonade you see a plethora of allusions to the Black Panthers and the Black Lives Matter movement, but she is able to explore the issues deeper through story with longer songs and lyrics,” they said

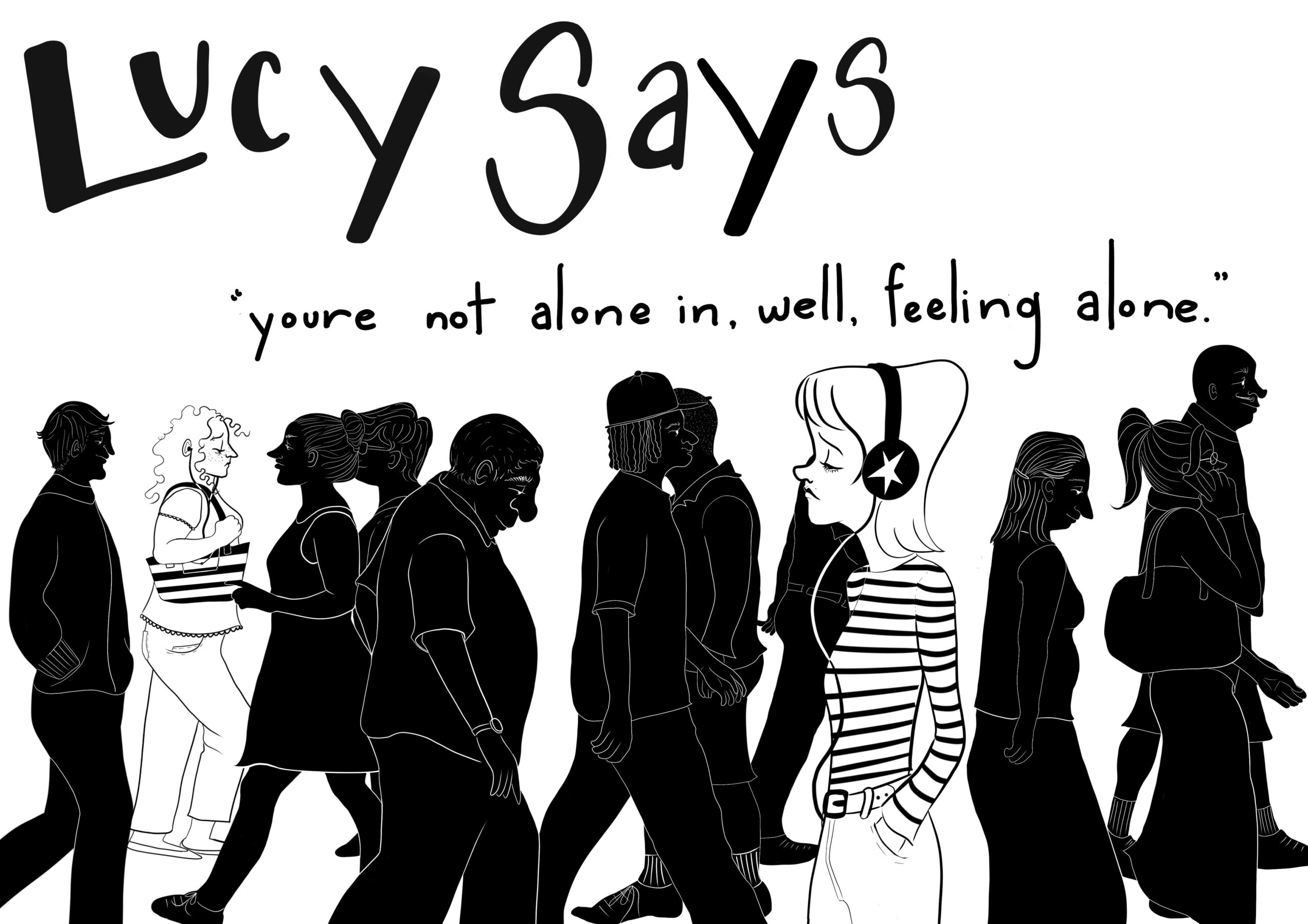

The energy and rhythm of these anthems are not necessarily the start to the political chants heard during protests, but they certainly of the same ilk. They garner the same sense of resistance, the same channeling of collective purpose.

“The political chant more importantly functions as means of bringing a collective voice together for one cause,” Jesperson states, “in protests, a political chant is an often terse way of loudly sending a message about a wider, more complex problem. Its purpose is to galvanize all of the different voices and perspectives on one issue into a single phrase or song that can be chanted by everyone, together.”

At their most complex, they instill a sense of solidarity and intention to those physically present, but they also reach beyond and into the offices of bureaucrats and onto screens worldwide.

Varon offered the widely popular chant “No hate, no fear, refugees are welcome here,” as a sophisticated example of what a chant has the potential to be. It’s snappy, rhythmic and to the point. According to Varon, it highlights the source of the resistance to refugees, namely the fear and hate coming directly from Trump and his chief advisor, Steve Bannon, a commonly unnamed enemy. It also reminds protestors and their audiences of the historic identity of the United States as a country that welcomes immigrants.

“It helps give a sense of common purpose to the people at any given rally and becomes a sort of shared language that can unite individual protests in groups across the country and the world who are sort of saying the same thing more or less at the same time,” said Varon.

In the contemporary resistance, there seems to be less of the sophisticated chant and more of the lazily strung together group of rhyming words. And the ever disheartening moment when a chant withers before it even begins.

“We’re losing a sense of the importance of the chant within our resistance culture,” Varon said. “In my lifetime there’s been, generally speaking, a withering of the chant.”

There is, perhaps, a reason for that. As a whole, our society is less organized around single ideas. Protests are populated more or less by singular agents not necessarily united outside that particular rally. Varon calls them “free floating political and moral agents.” Some call it slacktivism. This is seen beyond the realm of the protest – people have become more individualized in the age of the internet. That said, this isn’t necessarily a bad thing, as long as the intention is a departure from the past in order to create a more informed future.

Jesperson finds issue less in the chants that dwindle and more in those that display a kind of historic and political tone-deafness. They pointed to the post-immigration ban chants “we are all immigrants” and “this land is my land.”

“Both political chants are problematic in their inherent disavowal of Indigenous ownership of Turtle Island (North America),” Jesperson stated, “and the fact that not every person living on this land came through immigration.”

Ultimately, both Varon and Jesperson touch on an important fact: chants are tangible and valuable things that require accountability. That means looking beyond certain popular colonial rhetoric, but also embracing the spontaneous nature of political protest culture.

The world has vastly changed since the ‘60s, it’s changed since the ‘90s. It’s even changed since 2010. What worked back then will not necessarily work today. The hope is not to loose the power and energy of the past while building a stance for the future.

Illo: Ching Lan

This is an opinion piece. The views in this story are that of the author.