Fear tightened my throat as two male dancers, dancing in sneakers, shared an intimate, nearly five-minute-long duet in New York City Ballet resident choreographer Justin Peck’s ballet The Times Are Racing.

As part of NYCB’s Here/Now programming, which showcased four ballets from 21st century choreographers, Peck revived his contemporary portrait of America – this time with a male duet. Watching it, I sat afraid that this tender, tension-filled, energized dance between principal dancer Taylor Stanley, and corps member, Daniel Applebaum, would garner boos and even riots from the people in attendance.

For the dancers’ sake, I wanted it to be over quickly. Peck’s choreography drew out the moments of pure intensity when the dancers would simply hold each other’s stares, not touching, just looking. I eventually realized it wasn’t a quick, passing phase, but long with intention. I relaxed and enjoyed the rarity of seeing my reality play out on this historic stage.

As quickly as my anxieties had dissipated and I had given myself to the performance, tears streamed down my face and sobs filled my chest. I told a classmate after the performance, which garnered a standing ovation and four curtain calls, that I didn’t realize how badly I needed to see that.

Much of my life has been spent dancing, studying, and seeing ballet – though I’d never seen a same-sex duet from a world-class ballet company led by an openly gay dancer and a dancer of color.

As a queer, Mexican-American woman, that was the kind of intersectional representation I’d been craving from the ballet my entire life. Nonetheless, statements like this are rare, especially in NYCB’s repertoire, as evidenced by the nearly all-white casting of Swan Lake I’d seen only a few weeks before.

In the last weeks of September, I sat starry-eyed in my seat as the curtain went up for the fairytale classic. I was stunned to be seeing the legend whose footsteps I had aspired to follow since I was thirteen years old: principal dancer Sara Mearns.

The blonde-haired, white-skinned Mearns nailed the performance with her incomparable combination of speed, strength and artistry, leaving the audience dazzled – a gift they reciprocated with five curtain calls.

Despite witnessing Mearns’s talent, I was still disappointed. The nearly 88-person cast was made up of dancers who were as white as their swan costumes. There were 15 dancers of color, only seven of whom were darker skinned, thus more visibly of color to the audience.

The self-described “American ballet company” has been criticized for its lack of diversity. In fact, back in 2015, The New York Times covered the move towards diversity at Lincoln Center, which houses both the American Ballet Theater and New York City Ballet. The companies implemented diversity initiatives to recruit young dancers and train the next generations to include more dancers of color. Most recently, Dance Magazine focused on the newest program from the School of American Ballet (SAB), where NYCB dancers are trained and selected to join the company to help reinforce the diversity effort in its school. Along with expanding audition locations, SAB’s National Visiting Fellows Program recruits teachers dedicated to training dancers from “diverse backgrounds.” Whether they may become full-time faculty remains a question for the future, since NYCB only recruits from within to retain the Balanchine-style pedagogy.

Currently, the company boasts only about 15 dancers of color out of their 92-person company. That’s four principal dancers of color, out of 24; two soloists of color out of 18; and nine corps members of color out of 50.

As a person of color, experiencing ballet has always been difficult for me. As a kid, it wasn’t always apparent to me that race and ethnicity were the great differentiators. Kids don’t follow the rules of society (and laundry), and separate by colors and features. But I could always tell that something was off because of things that I couldn’t help.

It took me a long time to place exactly why ballet felt like something I was a part of from the outside; why teachers would make an example of me; why I always felt alone. Though they never let me forget that I was somehow different from the other dancers. Now I can articulate that it’s because the other dancers were tall, thin and white. I was short, curvy and Mexican-American.

Biases of that nature exist at the professional level as well. Despite efforts to support diversity, dancers who don’t fit a specific body type are told they don’t have the “right shape” for ballet. Or, as Joffrey Ballet School student and social media star Parker Kit Hill told Out Magazine in an interview about being gay and POC in the ballet world, though he identifies as male, he’s “not the correct male” by ballet standards.

Racism is the systematic oppression of people because of their race. Legendary NYCB choreographer George Balanchine dictated the willowy standards for female dancers, and in doing so he continued to exclude many of those who were non-white. The fact that this tradition was manifest before me today in a stage full of white dancers stunned me with disbelief. Did no one else feel the disparity? Or at the very least, see it?

“I’ve of course noticed it,” said Andres Mazuera, a porter at the Koch theater for nearly twenty years, although he “didn’t start seeing it as an issue until recently.”

According to Mazuera, after the City Opera’s departure in 2011 left a vacancy at the Koch Theater, they began contracting outside companies to fill that opening and bring in revenue when NYCB isn’t performing. These companies included Alvin Ailey, an historically multi-racial modern dance company, and American Ballet Theater, a slightly more diverse ballet company. ABT has more Asian-American dancers, as well as Misty Copeland, a dynamic dancer who became a household name in her own right far before she became the company’s first black female principal dancer.

It was when these companies came into Koch theater that Mazuera noticed that “it’s almost all color of the dancers and it’s still amazing.”

Though companies like Alvin Ailey and the historic Dance Theater of Harlem, which was the first African-American classical ballet company created by NYCB’s second African-American principal dancer, Arthur Mitchell, have maintained an adherence to diversity at their forefront, NYCB continues to preach only hiring and promoting the best, regardless of race. Looking back, I wonder what would’ve happened if I had seen more New York City Ballet dancers like me. I wonder if I would’ve ever had to quit dancing in order to completely re-establish the love I have for all of the qualities that make me different from ballet’s Euro-centric, heteronormative standards.

In fact, Hill explained to Out Magazine that he had to briefly leave the dance world in order to extract from the Joffrey Ballet School the respect for his race and sexual orientation as a Black, gay man. As Hill illustrated, it took his school losing him in order for them to start “seeing [him] as a dancer. Hill is now on a full scholarship and is performing in bigger roles.

Representation is an action that’s rarely given the weight it deserves – as rare as seeing professional dancers onstage that more of the world could relate to. This is likely because it’s never the people in power – the wealthy, the straight, the white, like NYCB’s typical audience – are never want for it. It’s the minorities, like gay people and people of color, that are forced to crave it. Or perhaps, it’s because of the tremendous impact it carries that it’s pulled from the forefront.

There’s significant power in seeing people like you succeed in something, whether it’s in the arts or outside of them. It gives the observer, who identifies with the victor, the comfort of knowing that whatever they want to accomplish isn’t impossible. Uncharted territory can paralyze many people, while for some it induces excitement, provokes them to pursue the challenge.

Underrepresentation hasn’t prevented gay people or people of color from entering the ballet world, for instance. But, because of the heteronormative traditions, the high cost of training and the racism inherent within the art form that typically reject non-fetishized gay narratives and body shapes of color, gay love stories are few and far between, and POC participation has been significantly deterred.

Accompanying those tactics is also the narrative that a dancer’s sexual orientation or race is irrelevant to the roles they perform. Dancers are considered blank canvases and the tools with which to paint them. This was once perceived as a positive. Now, because it only continues to reinforce the idea that diversity isn’t necessary, I consider it a negative.

Though it’s been almost four years since I left the painfully fraught world of professional dance behind, it continues to remain clear that as a major contributor to the conversation of diversity and representation, the proud “American” ballet company still has many years to go before it can definitively fulfill that title.

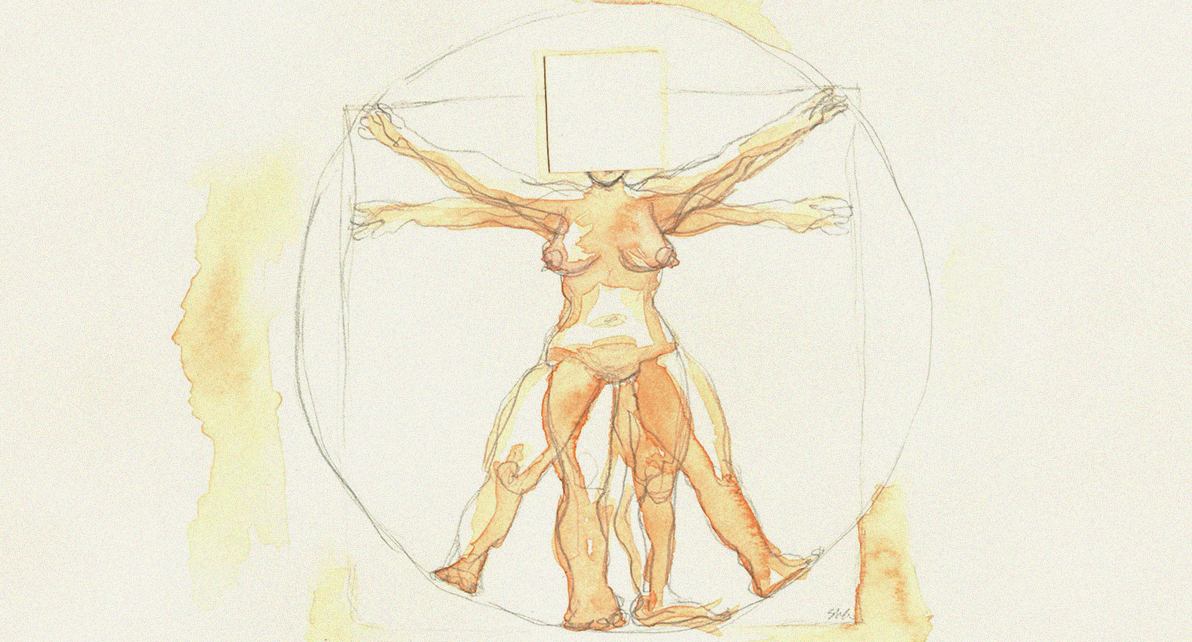

Illustration by Sophia Garcia