I found myself on a hill in Montmartre. Another hometown rockstar had broken up with me a few weeks prior. My sister and I were sitting outside at a cafe overlooking Paris, while the rest of our art class shopped for souvenirs. It was June and the day after my high school graduation, which I skipped for this trip.

I wrote down a chord progression that had been in my head for weeks. A minor, F and G. Music and writing are my eternal loves and often what I drop everything for.

A man at the table next to me began scribbling intensely in his notebook. He frequently took breaks to sip his hot, black coffee. I inhaled the crisp, French air, expecting to smell brewing coffee but instead breathed in something else. I knew that scent more than I knew anything. He was smoking a Newport cigarette.

My mind flashed back to when I was a sophomore in high school who spent weekends in New Haven, Connecticut. It was my first relationship. He always wore a drug rug, would die for indie rock and was a drummer in a band, when he wasn’t getting drunk. After each show ended, we’d hop in the back of the bassist’s black Maxima, as the backup guitarist stepped on the gas. I watched the speedometer go from 80 to 95 to 100, as I felt his hands cross into uncharted territory. Overdrive pedals, slashing gritty guitars and the ever-surrounding smoke from Newport cigarettes. Those were my nights. Those were our nights.

After him, there was the second, who had a Nirvana tattoo. My heart always stopped when he looked at me as he sang. He’d smirk, knowing I’d hopelessly stick around after his set was over. He had me. I was his naive, adoring devotee, and that was all I’d ever be.

I was the one he wrote songs about, he’d say. I was the only one who listened to his incessant rants about how the drummer couldn’t get his shit together or the complications he faced when the bassist wanted their song to lead with his riff. He always seemed to forget all that when another girl in the crowd lustfully gazed up at him.

I wanted to be more. I wanted to be on that stage and play on my own, but I was so consumed with being his to even listen to myself.

On this Parisian hill, I’d finally figured it out–or so I thought. When there was guy after guy, each one older with disheveled hair, a raspy voice and a Fender Strat, who said that I was beautiful or that he liked my extensive music knowledge, I’d immediately know what to do. I’d let his hands run across my bare skin; I’d let him get what he wanted, thinking he’d stay. And each time he’d leave, whoever he was, however similar to the last one he was, a part of me was surprised. The beat was inconsistent, each song never lasted too long and always ended abruptly, as fast and fiercely as it began.

That day in Paris, I told my sister everything. I told her about the first guy, the second guy and so on. I told her how I felt used and discarded, seemed to always be someone’s muse and believed I could never have my own identity. I thought I was just a body to countless people and would never be more–how I wanted to sing myself, but still be his at the same time.

Every man who has ever entered my life, even those who I had known since my infancy, swiftly departed once times got tough. This is simply a fact. A part of me just never wanted to believe it. “This one is different,” I’d tell myself, each time to no avail.

At the age of fourteen, I found books on classic rock and art history in my town’s library and became instantly enthralled with both. In James Young’s Nico: The End, Andy Warhol finds Nico, a soft-spoken beauty who needs his counsel to gain courage to sing and record her timeless songs. In Susan Alberth’s Leonora Carrington: Surrealism, Alchemy and Art, Leonora Carrington is a budding surrealist who can’t gain prominence without her more famous partner Max Ernst’s approval. In Whitney Chadwick’s Women Artists and The Surrealism Movement, talented painter Frida Kahlo’s work is overshadowed by her famous husband, Diego Rivera’s. In each of these, women I read about were written as if they could not create without some sort of male guidance.

I subconsciously garnered the notion that female creators need men to scoop them up under their wing, that notoriety was only ever accomplished through association, and I discovered everything I thought I knew about love to be problematic, outside that French cafe.

At fifteen and sixteen and then seventeen, I was unaware that each of their main objectives was to obtain my body because for a moment, I felt like I was adored for more than outermost reasons. I was the “fucking coolest girl,” one of them might say, since I “actually knew” who Ray Davies, David Gilmour or whoever else they idolized was.

In high school, and even up until now, I was always known as the “guitarist’s or drummer’s girlfriend,” but it doesn’t define me or any other girl who’s ever been described as such. Fellow female creators must know their worth. As trite as it sounds, there’s nothing I’ve learned in recent years that is more true.

However, in recent weeks, Ariana Grande and Mac Miller’s relationship is one case of muse and innovator, caught up in what many call, “The Yoko Effect.” Female artists who romantically link to famous male artists are often overshadowed by them, such as in Yoko Ono’s case, being married to John Lennon. They are also blamed for the male artist’s hardships, career changes and their ultimate downfall, such as in both cases.

Grande’s and Ono’s male partners were both drug addicts. This was documented before either of their relationships began. Yet, it seems the women in these relationships are always deemed at fault, whether for not taking care of their partners enough, focusing on their own careers too much, etc. All of these responsibilities only ever cater to one sex and not the other.

Male artists have been praised for their work throughout history, often to no end. No matter what their faults are, at times it feels as if they can do no wrong, or as if their own actions are never to blame.

Being a musician is integral to my identity, just as being an artist is crucial to Ono’s, for example. I cannot fathom only being known for who I have romantically linked to rather than what I create. It is time women who are also artists are recognized firstly as artists, no matter who their male partners may be.

We don’t need mentors; we don’t need Warhols in order for us to be Nicos.

We can discover ourselves without being rescued, and all we have to do is look to modern creators for guidance. Mitski shreds without ever stopping to apologize, and Bjork produces her own tracks without hesitation. This isn’t a time where we must depend on men for our own successes. As I encounter reminders of my past, I try to remember that. The difference between a muse and an innovator has always been assigned by gender.

The minute my unapologetic words were released to my sister, I felt all the more immune to some guy telling me that I didn’t use enough reverb, or that I missed a chord or my words were too long to be in lyrics.

Nico got sick of Warhol highlighting her beauty rather than letting her speak. Carrington created her best work after Max Ernst left her for another woman. Kahlo is now instantly recognized by her immensely influential paintings and not firstly as “Rivera’s wife.” We can endure much more than we think.

Now, if he leaves, whoever he is, I let him. If he stays (however unfamiliar that is to me), great. I just know it’s possible to create the best work with or without his approval, and that’s the most crucial aspect.

That afternoon in France, my sister stopped me. “Marissa, we’re in Paris,” she said, cutting me off mid-sentence. She pointed to a cobblestone path leading to a mountainside village – the houses Van Gogh used to paint and Hemingway used to write about.

“And they’re back in Connecticut,” I said. We both started to laugh. There I was in my dream city — unreachable, unobtainable and untouchable.

My sister and I grabbed hands and danced among the tourists as a street guitarist strummed his cover of Francoise Hardy.

I didn’t need some commitment-phobe rocker to get me there, and that was the essence of it all.

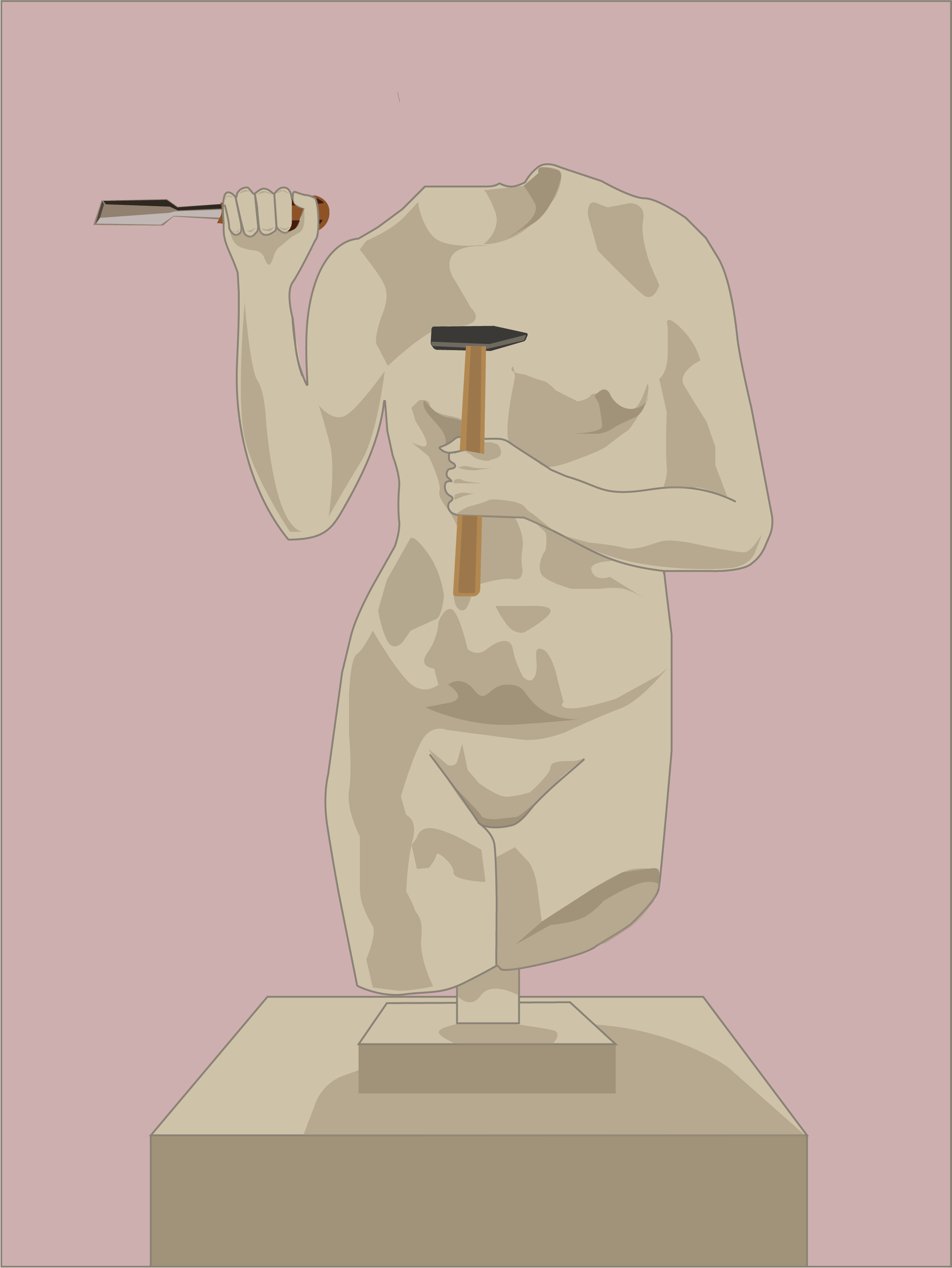

Illustration by Olivia Heller