When our classes take place in a comfortably air-conditioned, LEED-certified building that’s only been around a few years, it can be difficult to feel connected to school history. What could we, AirPods-wearing, tech-savvy college students, possibly have in common with a stuffy group of academics from a century ago?

[slideshow_deploy id=’18916′]

Over the past one hundred years, students have come to the New School for countless reasons and from countless places. As our curriculum has shifted, changed, and grown throughout the decades, so too have campus diversity, community, and environment.

Across decades and continents, however, the New School has kept one thing consistent. Whether by forming the University in Exile in 1933, offering the first college-level women’s history course in 1962, or this year having more international students than any other college in the country (according to US News), our school has been on the forefront of modernity and innovation since its founding.

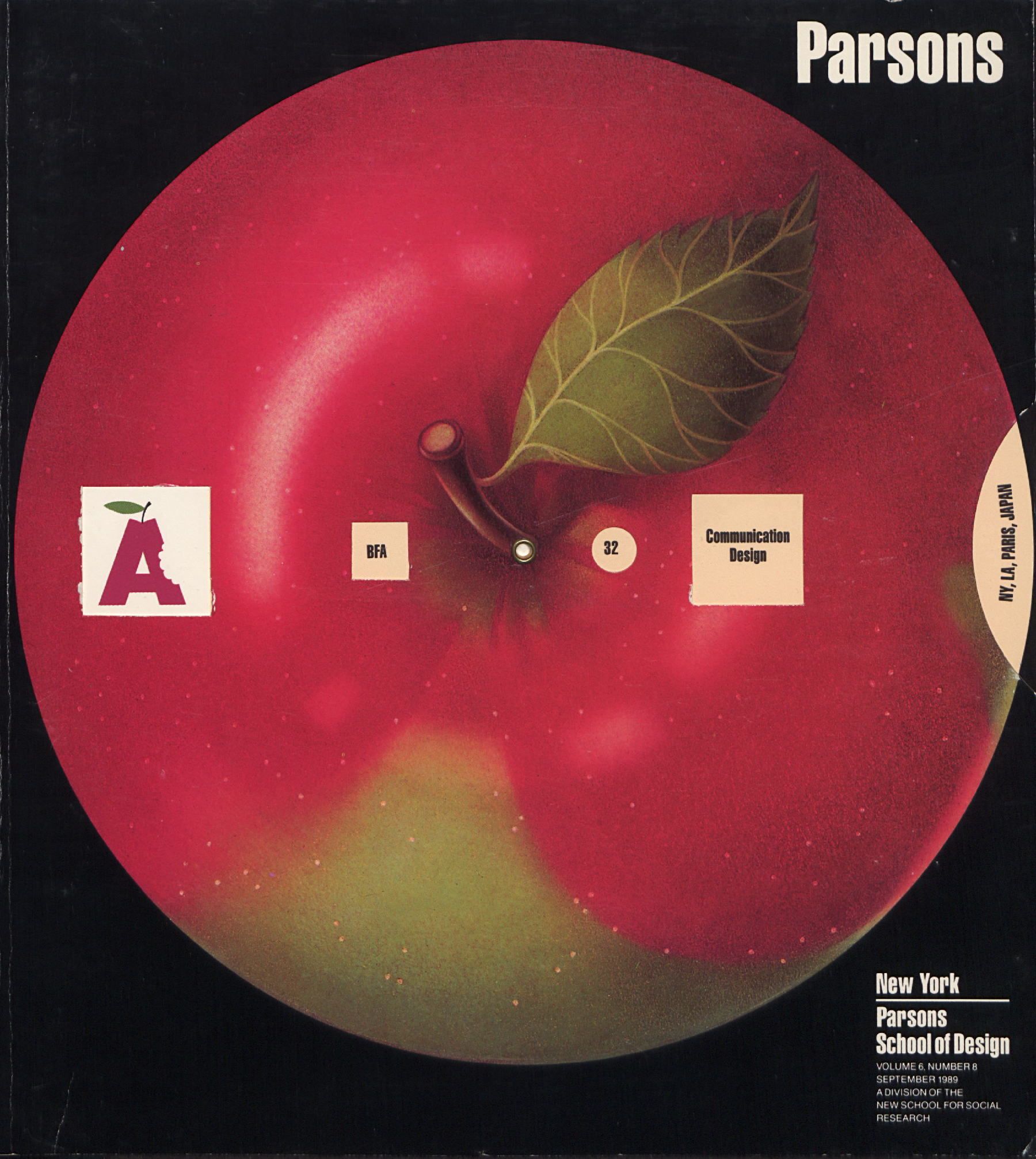

We are lucky enough to have access to this fascinating history, thanks to the New School Archives Digital Collections. The archives were established under the leadership of Wendy Scheir in 2012, then-director of Parsons’ Kellen Design Archives.In the years since, Scheir has worked tirelessly to document the history of the institution. One recent project of the archives has been to create a database of vintage course catalogs, which the provost’s office has helped fund.

“That project was one of the very first projects that we did as the New School Archives because we realized how incredibly valuable they were as a historical document, not only of the curriculum, but also because they provide a window into how the school wanted to talk about itself at any given time,” Scheir said.

From the very first course catalog published in 1919, featuring only eight lecturers and seven courses, course catalogs offer us windows into different points in school history. Unlike the website we know and hate today, course catalogs were widely circulated and, surprisingly, widely read.

“It was like the New York Review of Books. It was a thing that many, many, many people got, and people actually read through,” said Mark Larrimore, associate professor of Lang’s Religious Studies department and unofficial New School historian.

Course catalogs were hundreds of pages long. Each college had their own, published at the beginning of either each year or each semester. This meant that the archival staff had to track down, organize, and scan thousands of sheets of paper.

“We didn’t have all of these catalogs in the archives. We had to go around tracking them down, asking different offices to donate or if we could borrow their copies of different catalogs,” said Scheir. “That took us maybe a couple of months, just to gather them together.”

When these catalogs were still distributed around the city, nearly a third of their courses were never taught due to insufficient enrollment. This was intentional. Faculty whose classes didn’t run weren’t compensated, so the school could afford to offer as many classes as they wanted.

In the early 1960s, this is exactly what happened to Gerda Lerner. In the fall of 1962, she offered a course titled “Great women in American history.” This was the first class of its kind at an American university, and Lerner has been celebrated in academic circles for its design since. However, not enough people were willing to pay $35 to take two hours out of their Friday evenings and learn about “the history of the women’s rights movement through a study of its remarkable women leaders.” Although Lerner was unsuccessful on her first attempt, she tried again, and the course successfully ran in 1963.

“Another place wouldn’t have taken a chance on her in the first place, and after it was under-enrolled, they would’ve just given up,” said Larrimore. “Since it didn’t cost them anything, by virtue of the totally exploitative system they used, [the catalog] served as sort of an incubator.”

All good things must come to an end, however, and the school eventually stopped mailing out course catalogs by the thousands. With a steep rise in technology making it possible, course selection and advertisement took on a new medium: the internet.

“When we switched over from paper to online catalogs, the best argument was the ecological one. It was the right argument,” said Larrimore. A school so committed to sustainability simply couldn’t justify wasting so much paper when a computer can do the same job. Sadly, Larrimore says, the physical object wasn’t the only thing lost when this transition was made.

“It’s sort of like how people never go to libraries anymore. All of those great books you find that were right next to the one you were looking for, you’re never going to find again,” he said. “I think the old catalogs worked that way a little bit, where you’d just stumble across something perfect.”

Ten years ago it would’ve been almost impossible to find these hidden gems in old course catalogs, because they were stuffed on various bookshelves around campus collecting dust. After the New School Archives did the hard work of compiling and digitizing the hundreds of catalogs, they were suddenly accessible for anybody to learn from.

“The amazing part about digitizing them is that it really changed the kind of research people could do, said Scheir. “Not only did it provide this access, provide this information, but because you can now search across hundreds of catalogs in seconds, you can do a kind of research that wasn’t even possible before.”

The average class schedule this semester might not look much like that of a student 100 years ago, but while looking through all these course catalogs, no matter what it is you’re looking for, it becomes clear that our fundamental belief in a well-rounded education has not changed.

It can be difficult to branch out, to consider taking a risk and signing up for something entirely unrelated to your major, but just remember that our school has a deep, rich history of students taking classes just a little bit outside the box. And not so long ago, classes that we take for granted now, like women’s and gender studies, might not have existed in the first place if people weren’t willing to step outside of their comfort zones and sign up for Gerda Lerner’s class.

“If [your major] is something you’re really interested in, you’re going to have the rest of your life to work on it. And frankly, even if you take every single course in that field here, you’ll have to keep educating yourself after you leave,” said Larrimore. “There are some things you can’t learn elsewhere. Part of a well-rounded education is finding out what you can only learn, can only feel safe exploring, at college.”