Rumor has it that if you hang around the Lang hallways long enough you will eventually find your way in one of the hidden gems of The New School: the Orozco Room. With Fresco murals that cover the four walls of the room and a fifth one tempting you in right outside of it, José Clemente Orozco’s work invites discussions of politics and art, or it would if it were not closed off to the public.

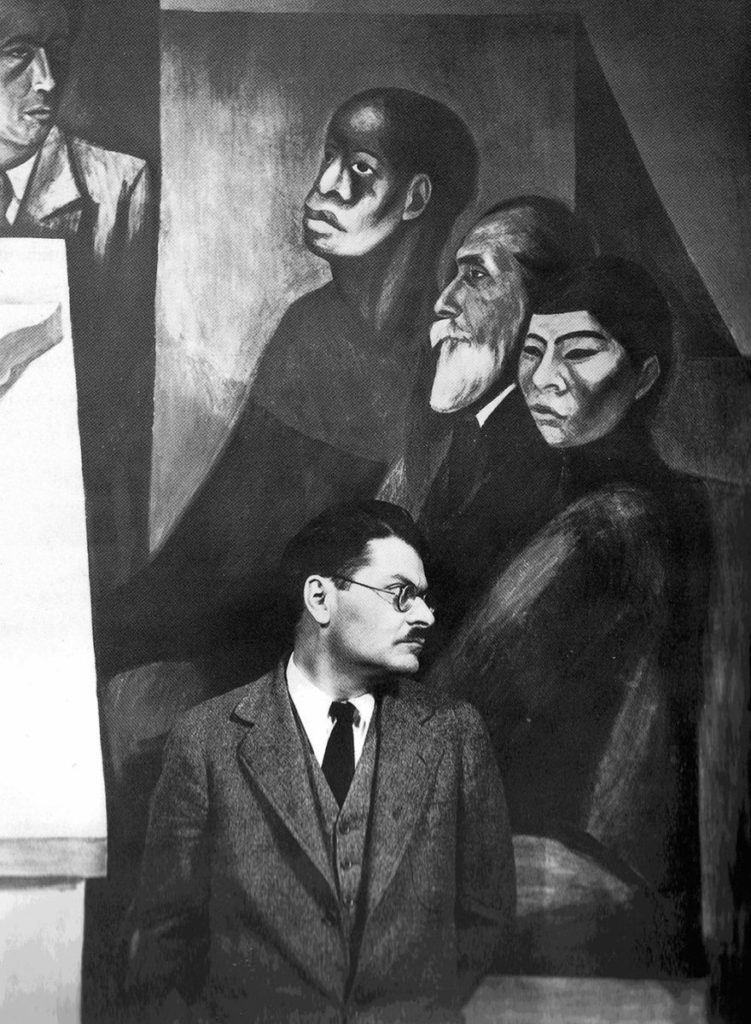

The Mexican painter’s work, “Call to Revolution and Table of Universal Brotherhood” was commissioned by Alvin Johnson, co-founder of The New School for Social Research, and was completed in 1931. The mural features images of family, community, slavery and resistance, accompanied by the faces of world leaders such as Gandhi and Stalin. The murals show support for communist ideals (not a surprise, as Orozco was part of the Mexican Communist Party). Orozco was a very important figure in Mexican culture, as he made up a third of The Big Three muralists along with Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siquieros. Alvin Johnson ignored critics and their political comments, he believed that the political beliefs of people are constantly “shifting” along with the end critique, in the Columbia University Press quotes Johnson saying “In 1931, the reviewers railed against the portraits of Lenin and Stalin. Ten years later, when the Soviet Union became an ally in the war against Hitler, the critics stopped complaining about Orozco’s rendering of the Russian Revolution and objected instead to his depiction of Gandhi, in a yoga position, dignified and serene, obstructing ‘the purposes of the British Empire.’”

However, while Orozco’s ideals are clearly present in his work, the closed doors that the murals sit behind do not reflect the same ideals. By limiting access to the pieces, TNS promotes the value of exclusivity in art that is hard to imagine Orozco would approve of.

Initially, the murals, which are located on the seventh floor of 66 West 12th Street, surrounded a cafeteria which was in the building at the time. It was accessible to everyone who worked or attended the school. The murals are now closed off, accessible only by request to the curator of the New School Art Collection or on the occasion that an event or meeting is taking place.

However, the reasons behind the room’s closure are not due to politics, according to Silvia Rocciolo, the collection’s curator, it is rather with the hopes of preserving the Fresco to the best of their abilities within the budget the school provides for the University Art Collection. The room itself was not built with the intention of holding space for paintings made with a base of water pigments and plaster. The humidity condensing in the room can harm the works. Providing a stable temperature in the room is quite easy, yet other forms of preservation are expensive. However, this chosen preservation technique of limited access seems to be imposing a direct opposition to the intentions of Orozco’s artwork.

It is not only in the images that Orozco’s ideals show through, as the medium he chose also played an integral part. Fresco murals, while not abundant outside of Mexico, are easily accessible: one of their influences is street art. Joes Segal writes for the Amsterdam University Press, “Images had the advantage over written pamphlets because they could also reach the illiterate […] Moreover, mural paintings had a venerable tradition in the region. They were already in use by the Aztecs and had been further developed under the Spanish colonizers since the sixteenth century.” Beyond their usefulness conveying messages to a wider audience, there are cultural connotations that are interlaced with the choice of mural artistry that cannot be ignored when speaking on the choice to keep the room closed.

Beyond the communist ideals that the piece presents, there are other implications that are not as obvious. Orozco was a Mexican artist, and in the current political climate, the choices of whose art institutions like TNS decide to display are part of a bigger conversation surrounding race and ethnicity, specifically conversations of gatekeeping and the ways in which latine communities are represented in predominantly white art institutions.

A different piece, inspired by Orozco’s work, hangs on the walls of The New School. Homage to Orozco #1 by Enrique Chagoyas hangs on the wall by the staircase going up from the first to the second floor of the University Center. The influence of Mexican artists is being celebrated by The Whitney Museum of American Art as well. An exhibition from February 17 to May 17, showing Mexican impact in American art, “Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art” features Orozco’s, Diego Rivera’s and David Alfaro Siquieros’ work. Currently, the exhibition can be accessed only through their website as the museum is closed to the public due to the COVID-19 outbreak.

Would Orozco prefer full access at the expense of the art’s lifetime? Through his artwork, his medium and his public opinion, it has been made clear that his political beliefs are all reflective of an open access to all work, especially his own. Living and engaging with the art is the ultimate purpose of a mural. I believe that Orozco would argue that it is the ultimate purpose of all art.