Story Update: The reporter and sources in this story wished to remain anonymous due to concerns about retaliation by the Chinese government under the Chinese National Security Law.

On a white tulip side table lies a piece of sheet music written in Cantonese called “Glory to Hong Kong,” a song that was written by a composer using the pseudonym name “Thomas” and with the contribution from the public on LIHKG, an online forum, in a time of turmoil in 2019. Given the intensity of the protests, this song of rebellion which was sung across Hong Kong is unexpectedly peaceful alongside colorful paper cranes. Nevertheless, it still captures the main focus of the exhibition, “We Are All Hongkongers Exhibition 2020”, which shows artists’ responses to pro-democracy struggles in Hong Kong.

The exhibition, which organizers say took over nine months and up to 30 hours a week to plan, features the work of over 20 artists, including graphic design, photography, video projections and short documentaries. The issues addressed in these artworks include themes of police brutality, universal suffrage, and freedom of speech.

The creative process of the exhibition has not been without challenges. Having no prior connections with artists, Bella, the main organizer who asked to be identified through a pseudonym, compared the experiences of reaching out to artists as similar to dating and marriage because of how long it took for her to gain their trust. She reached out to artists that she wanted to include in the show via social media.

Yet, when New York became the epicenter of the coronavirus pandemic, the project was forced to pause. “Our lives have been so greatly affected, you know, work, money, family. Everybody was shaking.” said Bella. However, with the slight improvement in May, the team started talking again about what the next step would be to continue the exhibition.

Inspired by previous Hong Kong exhibitions done in Tokyo and Paris and were live streamed on social media platforms, Bella felt compelled to bring the exhibition to New York, a multicultural arts center. Bella saw the exhibition as more than just a show of support for Hong Kong, but also for basic human rights such as equality and freedom of expression. “Whoever that believes in these basic human rights should support everyone around the world who is struggling and who is being suppressed.” said Bella.

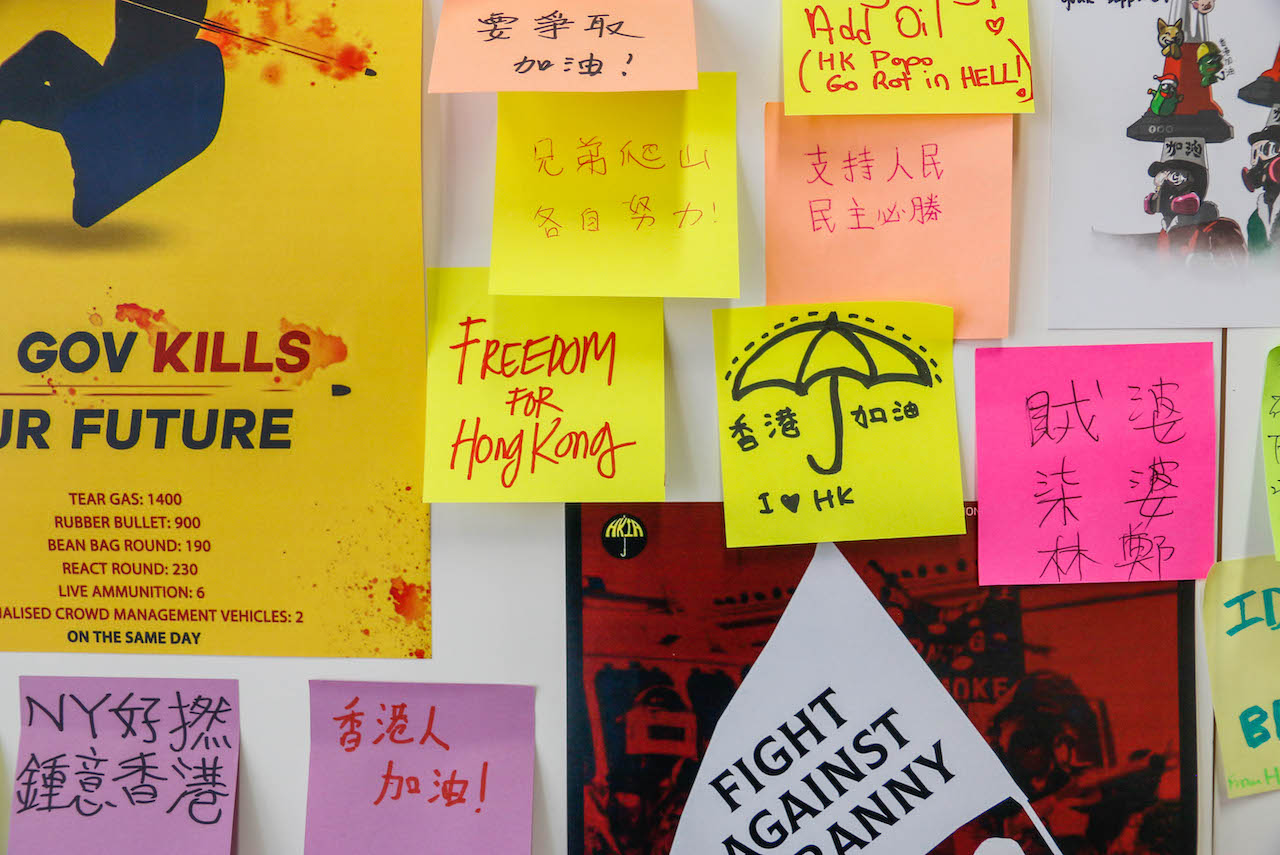

A main feature of the exhibition was a makeshift Lennon Wall where visitors are allowed to add their own personalized messages. The so-called Lennon Walls in Hong Kong were once loaded with sticky notes, posters, and flyers that contain messages supportive of Hong Kong protestors. The Lennon Wall first appeared during the Yellow Umbrella Movement, a large social movement in 2014 prompted by the Chinese government’s attempt at reforming Hong Kong’s electoral system. Once a tool used frequently to express political messages, the Lennon Walls are getting vandalized or quickly removed in Hong Kong because of the recent passing of the National Security Law which targets anything and anyone critical of the Chinese government under the guise of national security.

Sticky notes pasted on the wall right above the Lennon Wall formed the shape of a pink pig wearing a yellow helmet. Bella said the pig was what Hongkongers call the “Hong Kong Piggy,” a mascot and a sign of political awakening for the pro-democracy Hongkongers.

According to Bella, many Hongkongers used to live only to pursue a successful career and a good life, like a comfortable pig. “But this piggy in the last few years started waking up, and they realized that having money is not the same. I mean, it’s not enough,” said Bella, “You know, they want something more than just a comfortable life. It almost means nothing when you don’t have freedom.”

Artworks in the exhibition are largely created by anonymous artists, who wish to protect their identities while distributing their art worldwide through sharing on social media platforms and allowing viewers to download for free.

John C, who uses the pseudonym name “third blade,” is a freelance photographer and has been involved with Hong Kong activist groups since 2019.

A small replica of the “Lady Liberty Hong Kong” is one of John C.’s works. The statue, according to John C., is typically in one color such as white. However, in his version, he decided to customize the colors to make it closer to what a real protestor looks like in Hong Kong. In addition to the different colors, John C. used cotton in the sculpture to mimic the tear gas used by police against protesters in order to show the horror of battling in the Hong Kong streets.

Sharing the works about Hongkongers’ freedom struggle has inspired local and nationwide supporters to visit. An activist group called the Hong Kong Social Action Movement from Boston drove four hours to New York just to see the exhibition.

However, there are also people who have expressed their feelings towards the exhibition otherwise. Jeff Kung, born and raised in Hong Kong and now a 24-year-old healthcare strategy consultant in New Jersey, was hesitant about visiting the exhibition on purpose because he thought that the revolution is a painful memory to be reminded of. Growing up in Hong Kong, Kung never felt the need to participate in any social movements during school unlike the young people today using class time to protest against Chinese government. “Life in Hong Kong was not so as political as it is in recent years,” Kung said. “I mean it was always kind of there, but it was always a very, very small minority and it wasn’t strong at all,” said Kung.

Nine months of hard work turned into nine days of exhibition. When reflecting on the purpose of the exhibition, John C. said, “It is a way of telling the world that no matter where we are, as long as you are supporting Hong Kong and democracy for Hong Kong, you are all considered Hongkongers.”