The New School is an institution in pain and turmoil. Faculty and staff have already experienced pay cuts, the suspension of retirement contributions, and frozen research funds. Library subscriptions are being slashed. Course offerings have been reduced. More dramatically, approximately 13% of the administrative staff are expected to be fired by the end of the week, as announced in an email from the President and Chair of the Board of Trustees on Oct. 1.

These steps are being taken with seemingly little attention to their effect on the academic mission of the university, and with even less evident attention to the “social justice” goals to which the institution frequently claims to be committed. Moreover, these actions are being taken with little or no meaningful consultation with faculty, staff and students. They have been presented both as inevitable and as irreversible. Such executive actions violate the procedural norms that are widely expected of a modern university, even in an emergency situation, as articulated by the American Association of University Professors. The lack of consultation also means that the administration has failed to make the case to the university community that the measures taken are the best way to accomplish the stated ends.

The University leadership has made a two-fold argument: first, that the Covid-19 crisis has led to a worsening immediate financial situation, mainly due to a drop in enrollment and associated decrease in revenue, necessitating an immediate reaction, and second, that the opportunity should be taken for structural reforms to address financial vulnerability which had been brewing even prior to the current emergency—because of the increasing difficulty that families have in affording the ever higher cost of college, growing student indebtedness, and dependence on a few sources of foreign students. In making this argument, the administration has drawn on a point of view which has been popularized by some analysts suggesting that many American higher education institutions, characterized by high costs and diminishing demand, will have their very existence challenged by the current crisis, and have no choice but to shrink or even close. Some even argue that this should be welcomed, ushering in a new era of online education.

What are the merits of these arguments? Fundamental to evaluating them is the distinction made in a business between liquidity and solvency. A liquidity crisis results when there is insufficient cash to pay for expenses. A solvency crisis results when the “business model” is unviable, causing liabilities to exceed assets.

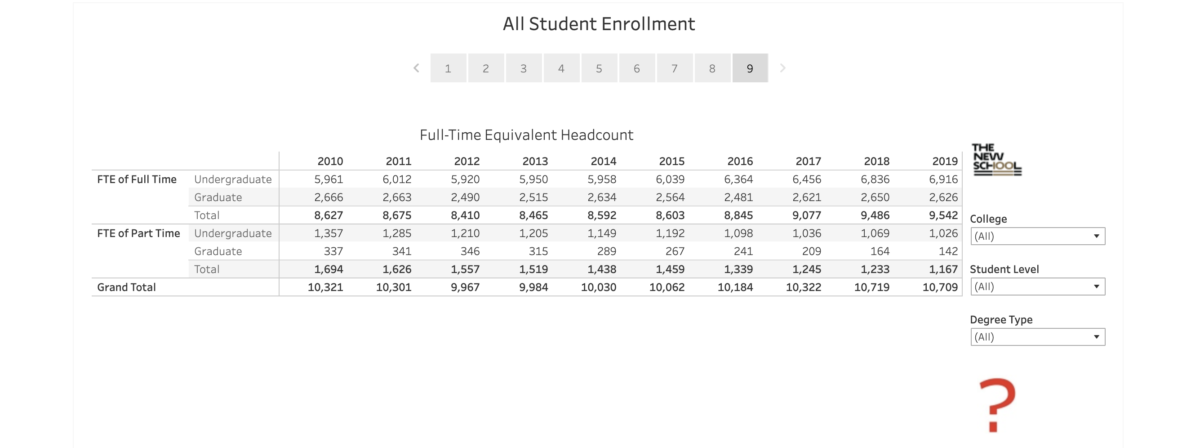

The New School faces a liquidity crisis as the result of a downturn in enrollments (“almost 10%” compared to what had originally been budgeted for, according to today’s email), leading to a decrease in the cash inflow needed to meet inflexible expenses such as salaries, rent and interest charges. The decrease in enrollments due to the Covid-19 crisis has been less than originally expected, but is still likely to have had a sizable revenue impact. It may also have ongoing effects, if a smaller entering class is only partially bolstered by transfer students in the future, but this adverse revenue impact is likely to peter out over time, once the Covid-19 crisis is overcome.

I have previously argued that the liquidity crisis can be responsibly handled through a combination of measures that might include a one-time partial draw down of the endowment, a special fund-raising appeal, refinancing of existing debt or additional borrowing to take advantage of historically low interest rates, and temporary cuts to salaries and expenditures executed in consultation with faculty and staff and based on principles of fair burden-sharing.

But does the New School face the equivalent of a solvency crisis, requiring immediate organizational restructuring and firings in order to return it to viability? There is very little evidence of a solvency crisis. Just prior to the crisis, university-wide full-time equivalent enrollments were at a near all-time high and had been on a sustained increasing trend. The university has been highly dependent on tuition and fees but its revenues have also exceeded expenditures in almost every year. Although the university may benefit from being “reimagined”, from improvements in its everyday workings, and from diminished administrative bloat, so as to enhance its academic mission and reduce its financial vulnerability, restructuring should not be unduly rushed. It should be informed by a careful study of experiences of members of the community – of what is working and not – underpinned by adequate public reasoning and justification, and guided by the academic mission of the institution. The New School’s “reimagining” process appears in contrast to be undertaken on a rushed timeline. Financial considerations appear to account for the urgency with which it is being pursued.

An atmosphere of emergency has been used to justify “structural adjustment” in countries around the world, often with little democratic consultation. As someone who has studied those experiences, I know that the actions that were taken in the name of collective salvation were too frequently ill-conceived and even proved counter-productive. What is happening today in the New School is a visceral reminder of such “austerity politics”. If the New School is to live up to its oft-proclaimed values, it must find another path.