In the fall of 2015, I was thrilled to be offered a job teaching Sustainable Systems at Parsons, an undergrad course where young designers learn how to improve the environmental and social dimensions of their practice. Although I had previously taught as a guest lecturer at universities across North America and abroad, the New School’s reputation for progressivism and innovation seemed a great fit for my values as a sustainability professional. It felt great to be working at a university where such luminaries as John Cage and Hannah Arendt once taught.

I was soon assigned two classes per semester and my student evaluations were consistently positive. After having gone through formal observation and completing 11 semesters of teaching (5.5 years), I attained “annual status” without incident. “Annualization” ensures job security. Annualized faculty have an ongoing courseload that the New School must fulfill in every academic year. Being “annualized” alleviates the precarity of part-time faculty life.

But at the start of my 10th semester, just before my annualization, I became aware of some disturbing new realities. Towards the end of the first summer of the pandemic there had been a long delay in receiving our letters of assignment for fall courses. My colleagues and I were left guessing, wondering if we could get our jobs back along with the vital health care coverage we depended on for ourselves and our dependents. On our frequent Zoom calls, we shared our anxiety as to whether we should start preparing our syllabuses or frantically look for other jobs. We all understood it was a precarious time for the university due to uncertain enrollment, even though we had heroically pivoted the previous spring, when the campus locked down, and we had to put in many unpaid hours reconfiguring our curriculums on the fly, so our students could complete their work online. It was a state of emergency, so we tolerated some uncertainty.

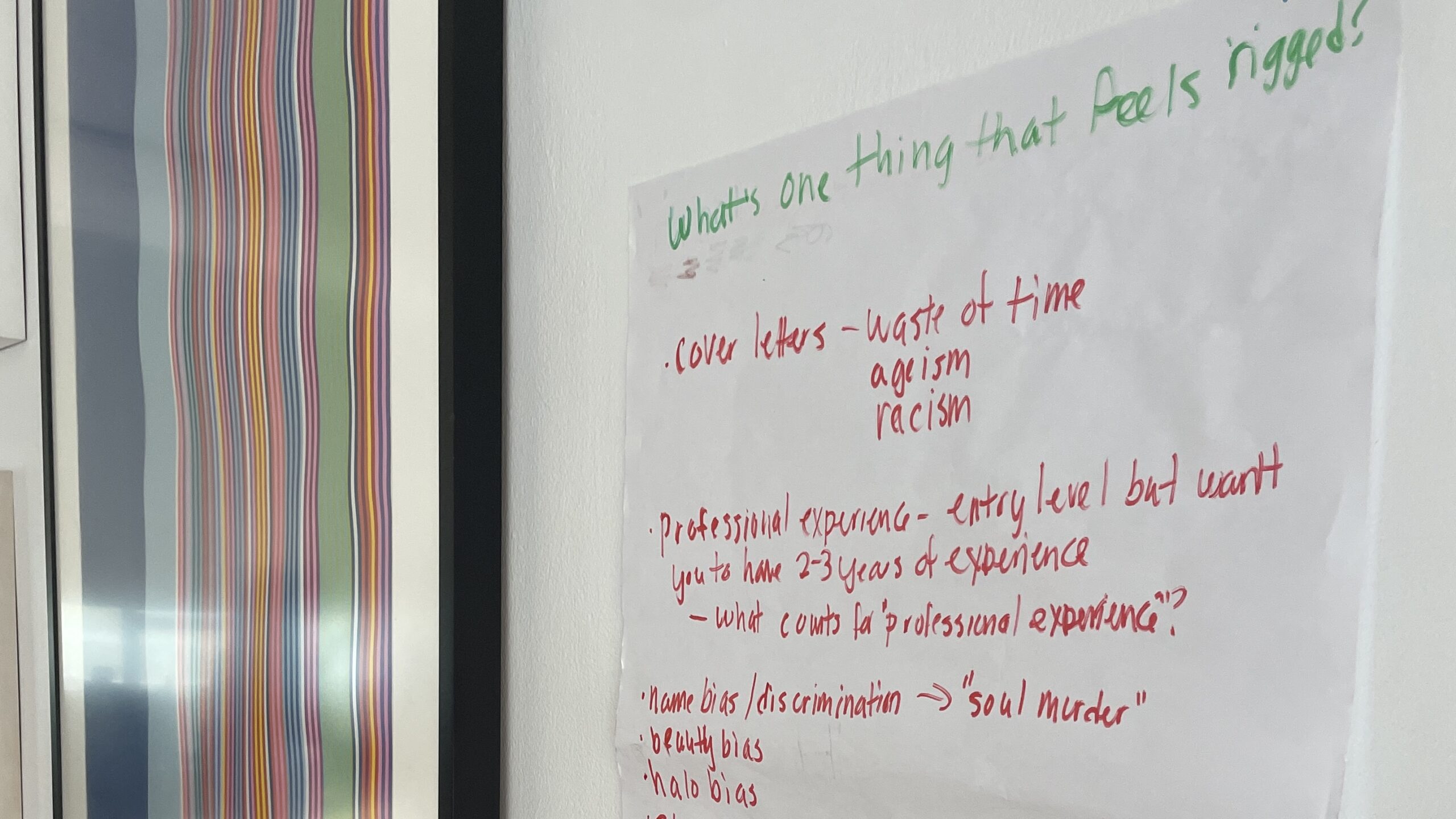

Imagine my surprise then when Fall of 2021 came around, with the return of in-person teaching and record student enrollment, and I found out several of my part-time Parsons colleagues, who had taught multiple semesters with good student evaluations, would not be hired back, with no clarity as to why they were terminated. At the same time, several new faculty were hired from outside, for the same positions. The university’s message was clear: the path toward annualization was no longer a given for faculty who had put in years of hard work and commitment to their students. We were now regarded as a disposable asset to be tossed aside for no good reason – ‘human resources’ to be turned on and off as needed like a tap. Though I was teaching my students about sustainable systems and circularity, the university was treating its part-time faculty like single-use plastics.

The principle of seniority, a cornerstone of labor justice, seems to have been thrown out the window by management. The pandemic was being used as cover for a brand of disaster capitalism that should have no place in an institution of our storied reputation – an institution in which our president recently reminded us – ‘faculty, and staff work so tirelessly and passionately for social justice.’

The outcome of this austerity-minded management style, for part-time faculty across the university, is an overriding newfound nervousness about the contingency of our relationship with the university. It has been made clear that there is little stake in our professional advancement or the long-term community building that comes with a clear path to job security. Unsurprisingly, morale and commitment to the institution are at an all-time low. These are not the values The New School publicly espouses, and I believe management and part-faculty must work together to put this right.

We need openness and transparency as to where post-probationary part-time faculty stand in their path toward annualization. If faculty are not rehired after multiple successful semesters and not offered suitable substitute assignments, they deserve clear reasons.

Outside faculty should not be hired to replace existing faculty still waiting for their course assignments. This is deeply disrespectful to established faculty who have labored hard over multiple semesters to make their courses great, and cheapens the experience of the new hires too, who are left to wonder whether they were only taken on because they are cheap assets, too new to qualify for benefits, and ultimately disposable themselves.

The New School has always strived toward invoking optimism and building a better future. I am proud to be part of that tradition and call upon the university to commit to fairness and transparency in its labor practices so we can continue to live up to the high standards of humanity and justice we are recognized for throughout the world.