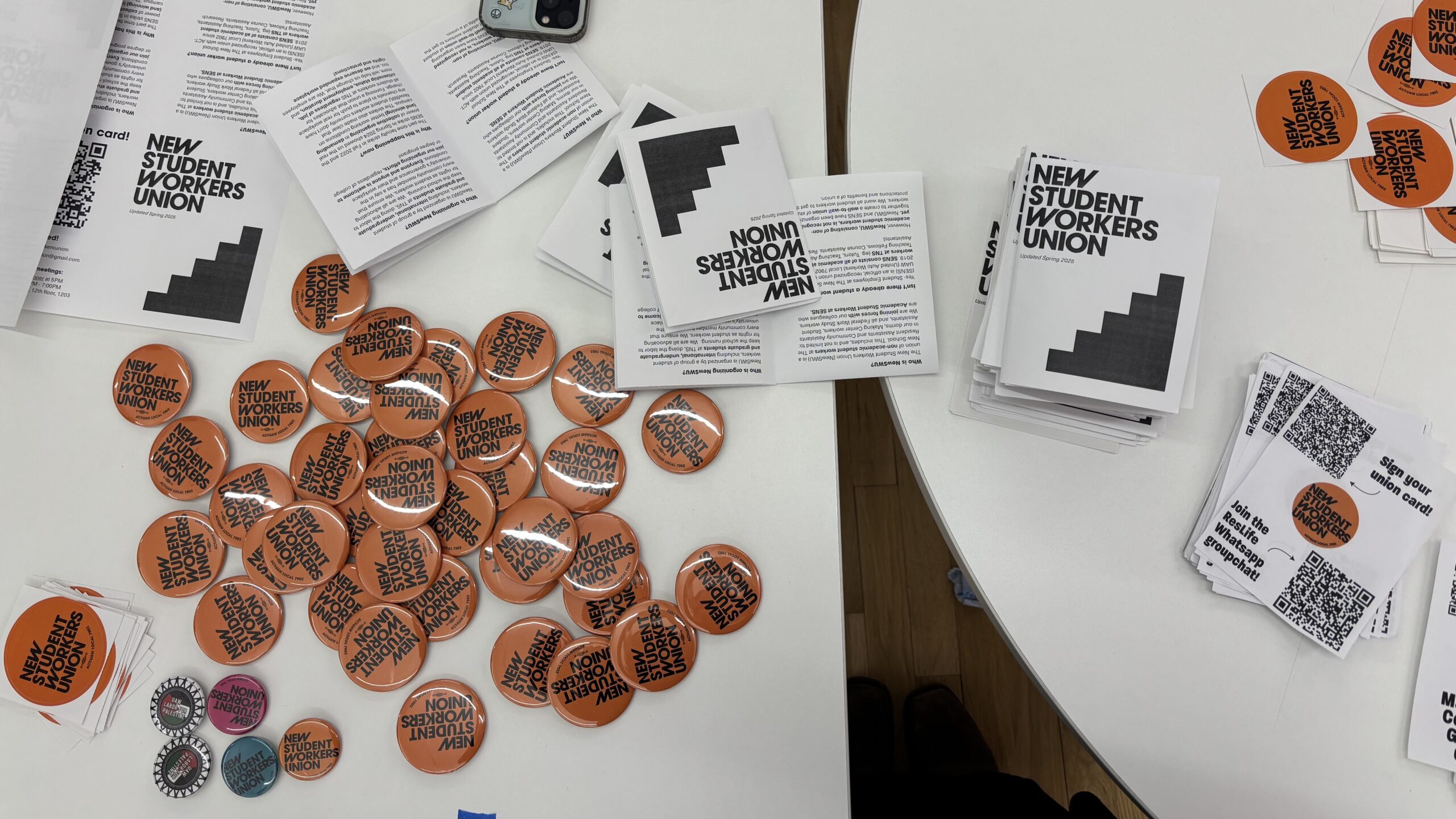

“When you see a slide, it’s incredible. It’s one of the most beautiful things in the world,” said Drew Adler, a lab tech and co-owner of Exposure Therapy, a photo lab in South Williamsburg. Sitting behind the glass counter at the store, Adler discussed color slide film, a unique version of color film on the verge of extinction. Beloved for its entrancing colors, the film itself is unique because the image appears as intended on the film itself and does not have to be printed or scanned. Listening to Adler discuss the subject, I nodded and smiled, recalling my own years-long journey to shooting slides.

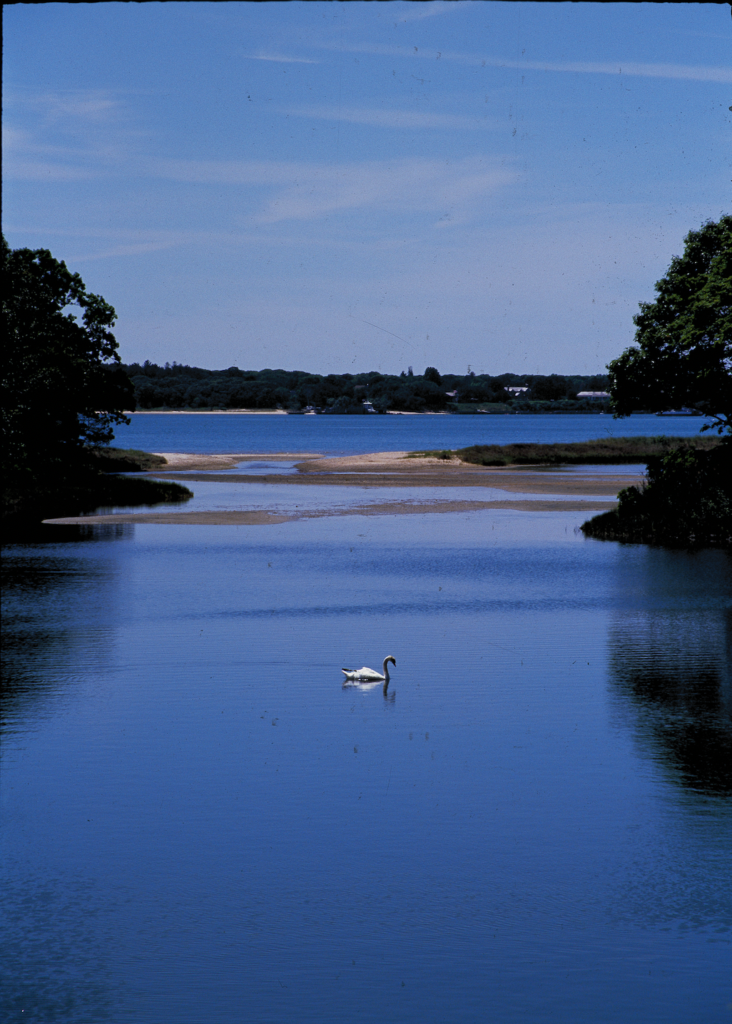

That first roll was revelatory. My first results were noticeably different from anything I had ever shot before using other formats, but the subjects had not changed. The color saturation of my slides was so striking that it made most of my subjects appear neon. The highlights and shadows in the images seemed extreme, pointing out in stunning detail the errors I made while shooting. Many of the shots were incredibly under or overexposed. I was shocked. I had not expected any color film to return images other than the soft, pastel color palette I had seen so many times online. I had spent $35 on buying and developing the roll only to receive two images (out of 36) that I deemed worthy of showing. I wondered what the appeal of this film type was, considering its high cost and the scarce availability of processing labs.

Slide film was invented by Kodak in 1935, and was very common for the rest of the 20th century. As film evolved, it was replaced by other mediums, like color negative film and digital cameras. Even now in the revival of film photography, slide film continues to be neglected. Color negative film remains the most popular type of film, packaged in disposable cameras and single rolls and sold in almost every camera store nationwide.

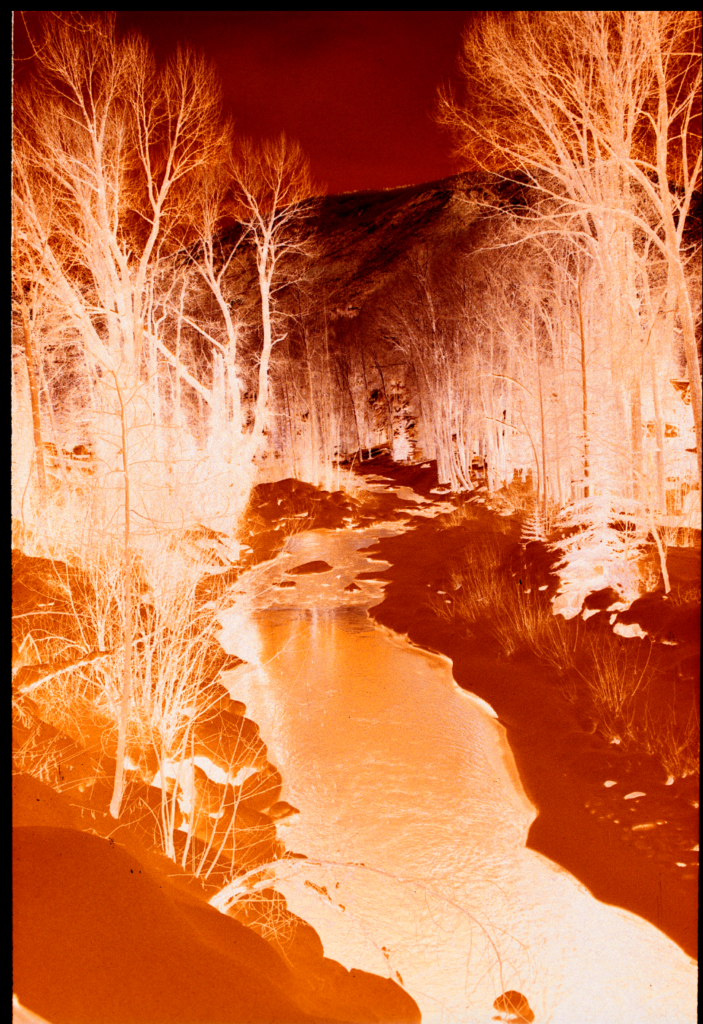

Adler believes that the resurgence of slide film came at the beginning of last year, when HBO announced the entirety of Euphoria’s second season was shot on Kodak Ektachrome, the only slide film left in the company’s lineup. Adler explained that the results consumers were going to get would be entirely different from that of the show, because it was cross-processed, and digitally color corrected for consistency, as is common for cinema and television. ‘Cross-processing’ refers to the practice of processing film in a different chemistry than intended. This often leads to inaccurate color renditions, but more flexibility in editing.

Regardless of any complications, I wanted to give slide film another shot. I turned to the wisdom of film photography veterans on internet forums to prevent future embarrassment. I found that the saturated look is an intentional feature of slide film, making it a fan-favorite amongst experienced film photographers like Pete Turner and Galen Rowell. They were able to compress the scene through intentional under/overexposure or through the use of colored filters to boost saturation in their images. After many years of working with these film stocks, it has become a staple of my landscape workflow, and I can record the image on film the same way I visualize it in my mind.

Adler knows the struggle of slide film all too well. He develops it at Exposure Therapy himself, a process he calls “messy” and “disgusting.” Color negative films use C-41 processing, a simpler process that takes just over three minutes. Color slide film uses the E-6 process, which requires six steps and varying processing times for each chemical. Developing slide film brings the store no income, he said. “We do it on principle. It gets customers in the door!”

As of 2023, there are only three slide film stocks left in production that use the E-6 process: Kodak’s Ektachrome, and Fujifilm’s Velvia and Provia films: all of which are slow speed (low ISO) options with thin exposure latitude, meaning that slide film provides little flexibility for photographers that choose to use them.

For most photographers, this means that slide film can only be shot in bright, outdoor conditions, and photographers must make very careful exposure calculations on the fly to ensure pictures have a full range of tones from highlight to shadow.

When exposed and processed properly, there is little-to-no grain in the image, and colors pop brilliantly. Speaking on the modern-day appeal of this archaic medium, Adler said “Slide film is the closest you can get to digital with color film because there’s no grain, and colors appear straight out of the box.” Most film processed today is scanned, as opposed to darkroom printing processes of the past. “If you get a good [slide] scan, it looks better than digital,” Adler said.

One of the reasons I, and many other photographers, have been drawn to slide film is because of the aesthetic choices it makes for you. Slide film gives my landscape images an extremely saturated look that allows me to communicate through color and sets my portfolio apart from my peers. The rich color and stark contrast are baked into slide film as a medium; it then becomes my responsibility to weave these predetermined rich colors and shadows into my signature ‘look’ within a body of work.

Having to adapt to slide film, a rigid and inflexible medium, has added a new dimension to the aesthetic I have sown into hundreds of film rolls. I am able to capture and communicate emotions through the bold color. The inky blacks and pearly whites I love are not something that can be obtained easily through the more gradual tonal ranges of digital sensors or color negative films. With the click of the shutter, and the thousands of chemical baths drawn by the photo labs that go through the trouble of processing it, my slides (and your grandparents’) will live on.

Leave a Reply