A look into the leaders of Indigenous Futurisms

This story was updated on Sunday, March 24th at 6:50 pm.

The imagined future

The sun hovers just above the land, radiating a golden hue over the tall grass. In the distance, a man and a child forge a path through the thick field, their bright regalia flowing behind them in the gentle wind. As they come closer, a ‘click’ sounds off in the background, and a grainy audio of a man speaking emerges. Other voices can be heard behind him, humming and chanting powwow tunes.

Now, the man and child stand fixed. They turn to one another and the man bends down, leveling his face with the child. He places his hands on either side of their head, saying something that can be assumed to be sacred given the intensity of the moment. The man’s hand drops and reaches for a piece of regalia lying in the grass. He slowly rises, placing the regalia on as the child watches in awe.

Suddenly, through some sort of silent agreement, the two begin to shake their heads, the fringe on their headdresses whipping from side to side. The motion continues, the lingering voice softens, and everything fades to darkness. Now, staring into a black screen, the last words are spoken as the voice calls out, “After all, these are our problems. If we don’t do something about them, we cannot expect someone else to be concerned enough to solve them for us.” Then, there’s a final ‘click’ and it’s over.

As I look at the blank screen, waiting for more, I only see myself staring back. The last words ring in my ears and I close my eyes, imagining this world. I ask myself, “What will it take to get there?”

This place comes from the imagination of Cannupa Hanska Luger as a prelude to his art series “Future Ancestral Technologies.” He, the man, and his son, the child, wander through his homelands on the Mandan Hidatsa and Arikara Nation in North Dakota, which have since been ravaged by fracking and oil drilling. Together, they wear regalia made by Luger and move to the voice of his grandfather, Carl Whitman, from an audio recording taken in 1984. This “performance” displays Indigenous peoples existing in their most authentic form and on the land taken from them; it is an act of reclamation and part of a revolutionary movement.

An Introduction to Indigenous Futurisms

This movement is an ongoing quest to a future where Native peoples can live freely, healing traumas and preventing further forms of modern colonization. It can be defined as “Indigenous Futurisms,” and it is just the beginning, as artists like Cannupa Hanska Luger are forging a path to this future.

To navigate the realm of Indigenous Futurisms, it is important to first understand the origin. Although this movement has arguably been around since colonization’s inception, the term “Indigenous Futurism” was first coined in 2003 by Anishinaabe Native scholar Grace Dillon. Inspired by pre-existing futurisms like Afro-Futurism, Dillon aimed to establish a framework specifically for Native peoples.

In her research, she created the first-ever published work of Indigenous Futurism, an anthology called “Walking the Clouds,” which consisted of science-fiction-themed stories from Indigenous artists around the world. “I had it in mind to compile a collection of stories that had already been written, but established that Indigenous Futurisms had been here for quite a while— it was just that we weren’t paying attention to it,” Dillon said.

Since “Walking the Clouds” was published in 2012, Indigenous Futurism has progressed as it is now referred to plurally as “Indigenous Futurisms” to recognize the multitude of possible futures for all Native peoples. This name change and evolution of Indigenous Futurisms at large has invited collaborators from all fields to join this movement, artists being among them.

Indigenous Futurisms through the vessel of art

While there are many reasons why art is one of the leading modes in which Indigenous Futurisms are conveyed, the main one is that art is a universal language that has the power to communicate concepts that everyone can understand. Art has been made the most digestible form of Indigenous Futurisms, making it crucial to support the artists pushing it forward.

There are many methods for representing Indigenous Futurisms through art, as individuality is what differentiates the artists within this space. However, some common means exist in how it is expressed, such as an emphasis on science-fiction, land, space, and materiality. With these themes in mind, Indigenous artists can envision their archetypal futures.

Contemporary artists within this field have taken elements of Indigenous Futurisms and morphed them into their own definitions, recognizing how Indigenous Futurisms is a shared goal among Native peoples and can be imagined within any realm of possibility. Among them is Cannupa Hanska Luger, a long-time artist pushing the boundaries of Indigenous Futurisms.

Cannupa Hanska Luger: Future Ancestral Technologies

Luger’s performance piece within “Future Ancestral Technologies,” that he filmed on his homelands is referred to as, “Transmission Fluid 2042.” This was born out of a realization to create his unique brand of Indigenous Futurisms—one that represented his individual Native experience. In this project, he utilizes knowledge passed down to him from his elders, as well as the lessons he has learned through his own life to manufacture this space.

This future is built in a post-colonial and post-capitalist society, where revitalizing Indigenous culture and the relationship with each other and the land is prioritized. Not only was the ethos of this project thoughtfully constructed, but so was the name itself. Luger took part of his ancestral knowledge—Lakota, one of his Native languages—to formulate a name with a double meaning.

“In Lakota, white people are described as ‘wašíču’, which also means ‘fat taker’; the acronym of my series Future Ancestral Technologies is F.A.T,” Luger explained. “What I’m producing with this work is the fat, this generative thing, that allows energy to move through people and generations. Many green economies are co-opting Indigenous ancestral technologies without honoring the communities where that knowledge comes from or the people who carried it for generations. That way of taking is wašíču, and as a species, we must acknowledge and respect the cultures who sustained these ideas to truly impact our future survival.”

This “fat” takes form in nine installation pieces, each portraying a diverse component of Future Ancestral Technologies. One of these pieces titled, “We Survive You” displays a room where on one side sits a van with regalia hanging from its doors, a woven structure on its roof, and other small characteristics that Indigenize the modern automobile. On the opposite side of the room is what appears to be a tapestry, but is described as a “Transportable Intergenerational Protection Infrastructure,” which intentionally spells out “TIPI.” On the wall adjacent to the structures are painted weapons of various forms and a radio with an eye installed in the center that watches over the space.

“This piece is called “We Survive You,” because as Indigenous peoples, we have survived so far,” Luger claimed. “We exist in a future space—with great effort and care from generations past and present—we exist in the future and we thrive on our cultures, our stories, and our myths.” Through “We Survive You” Luger engrains sacred teachings of his culture to ensure its survival — a shared goal among futurists. His stress on survival through his work comes from his experience as a Native father; he now has the responsibility to pass down this ancestral knowledge to his children like his elders taught him.

“Every ounce of Future Ancestral Technologies was built post-becoming a parent. I’m trying to leave a physical anchor that creates an archive of teachings and stories so that my kids may learn to be valuable in the future,” Luger said. “It’s like creating a stash for that knowledge but you don’t have to hide it in a tree, you build it up in your children which follows into future generations.” While Luger continues to expand his world of Future Ancestral Technologies with new projects, including one currently exhibited in the 2024 Whitney Biennial, a generation of artists are stepping into this space to build their own futures.

Cheyenne Rain LeGrande: Mullyanne Nîmito

Cheyenne Rain LeGrande is among this new age of Indigenous futurists. LeGrande is from the Bigstone Cree Nation in Canada, which is emulated through every facet of her art. Through installation, photography, video, sound, and performance art, she carries with her the traditional practices of her Cree ancestors while simultaneously implementing materials and other elements of modern Indigenous culture.

Her project, “Mullyanne Nîmito”, which she made as a part of her Banff Artist Residency, is a display of this marriage, and arguably her breakthrough Indigenous Futurisms’ performance piece. For this project, she collected 3,300 soda can tabs with her community over five years. With these tabs, she used traditional weaving to mend them together and construct a wearable shawl, embellishing it with multicolored strands of ribbon.

This shawl was then incorporated into her performance of the Fancy Dance, a contemporary powwow dance. As she danced, it became translucent and revealed imagery from her homelands projected on the wall behind her. She shared this moment with her mother, who sang and read words in Cree, while her partner videographed the performance.

This piece where LeGrande’s close community came together to produce an exhibition of Cree culture is what her line of Indigenous Futurisms aims to do. LeGrande credits materiality as the tool in which she can extend her culture to those outside of it, inviting others to join her future space. “In the process of making this shawl, I was thinking about my ancestors and how they made garments out of everything around them in nature,” LeGrande explained. “For me, it’s so different to think, ‘What do I have access to around me that is getting thrown out?’ So this was a way for me to reuse something that I see all the time.”

LeGrande has expanded the theme of reclamation outside of materiality and into other areas of her practice. One of these areas is her Native language, which she has dedicated to maintaining by learning modern songs that are translated into Cree, most recently being “Dreams” by Fleetwood Mac. “My Nimama [mother in Cree], and Kookum [grandmother in Cree], helped me translate ‘Dreams’. Knowing all the words to that song is so special to me because it’s my way of having access to a language that I’ve lost,” LeGrande said.

LeGrande’s art is not only an act of reclamation, but a constant tribute to her ancestors. Although she first sought out art as a form of healing her intergenerational trauma, as many of the practices she now carries were almost lost to colonization, she now uses the journey she’s taken in healing through art as an anchor to relate and connect to those who view her work. “I hope the audience can learn from my art and understand our stories, everything we’ve been through, and the beauty that we behold,” LeGrande reflected. “I want them to be able to feel that while also healing in the process.”

Her next projects maintain the elements that have been consistent throughout her practice while also exploring new terrains. She plans on making another shawl out of tabs, but this time it will glow in the dark to honor the stars and the Northern Lights she looked up to while growing up. For now, her newest work of Indigenous Futurisms is her very own shoe, which are moccasins that she put platforms on the bottom of to make a hybrid shoe of both traditional and contemporary Cree fashion.

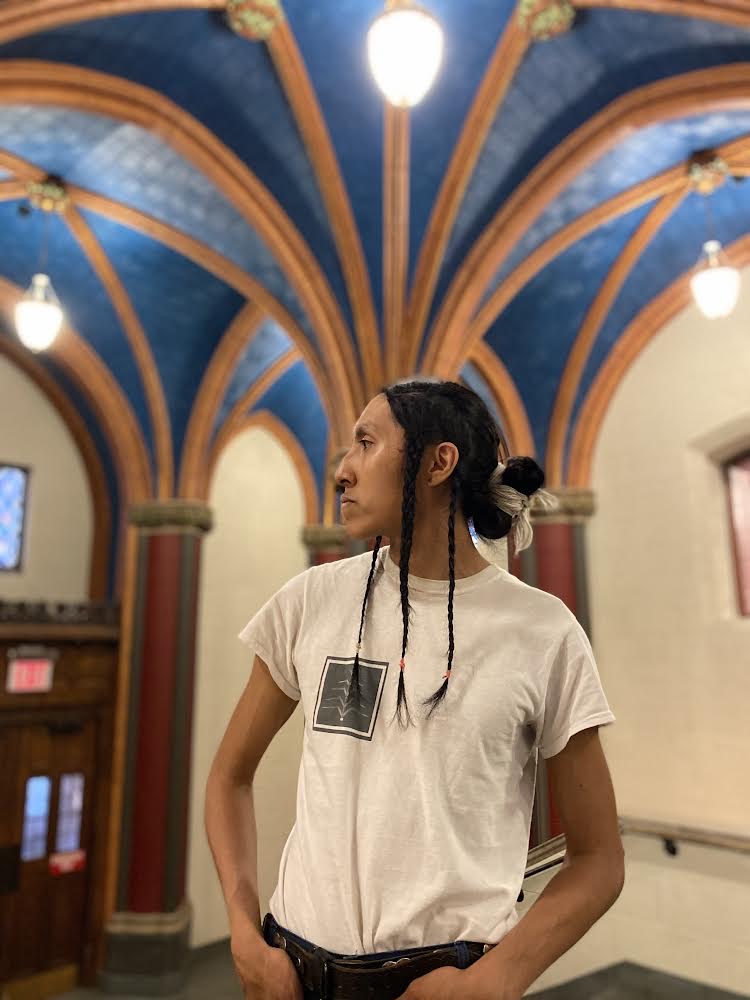

Ty Fierce Metteba: Free-Spirit Artist

One of the most recent collaborators to join the Indigenous Futurisms movement is Navajo “free-spirit artist” Ty Fierce Metteba, whose futurism is displayed through an obscure collection of multidisciplinary mediums. Their pursuit of these diverse interests began when they were growing up on the reservation in Arizona. In high school, they excelled in mathematics, while also having an innate passion for art in every medium. This led them to fuse these interests and start their work, conveying Indigenous Futurisms through these combined practices.

Their version of Indigenous Futurisms doesn’t conform to any structured project but rather carries a continuous display of it in everyday life, hence the self-claimed identity of “free-spirit artist”. One of their pieces manifests in Instagram videos of Metteba dancing, which they started as an alternative way of showing off their outfits, but has now become a constant form of practice. “In these videos, I’m dancing, I’m feeling myself, I’m floppy and off-beat, because why not? This is liminal space, ” Metteba said.

While dancing and other mediums come naturally to Metteba, they attribute some of their practices to other futurists in the space. Through taking inspiration from Indigenous collaborators, they diversify their expressions by implementing their own knowledge, history, and relationship to this movement.

“Cannupa Hanska Luger’s art is something I resonate with. I want to be this random monster that dances through time because this is what we want for Natives,” Metteba claimed. “His work is this total exhibition of Indigenous Futurisms.”

While art is always in motion for Metteba, they continue to thrive in academia as they’re obtaining a doctorate in Mathematics Education at Columbia University. Their diversification of futurisms, whether that is through math, dance, or artistic installations, attests to the expansiveness of the framework. Their journey through these mediums is just a separate path forged through the same field of the future.

“My art has made me come up with this idea that the Navajo identity is limitless,” Metteba reflected. “This is just another reason why Indigenous Futurisms have to be adopted by everyone.”

The future

Grace Dillon, Cannupa Hanska Luger, Cheyenne Rain LeGrande, and Ty Fierce Metteba have all created maps to a decolonized future through art. In various mediums and many expressions, these creators have utilized the language of art to transfer ancestral, sacred, and cultural knowledge that fuels an ongoing movement. They have proven in every way that art is the door to these dreams of a future.

I remembered the world that Cannupa Hanska Luger had built for him and his son, and I imagined my own. I began to feel the warmth of the sun against my skin and I ran my fingers through blades of grass. As I walk, my regalia floats in the cool breeze. Music comes from somewhere beyond, and I begin to dance. I move through this field with no fear and no limits. This is a world where I, and other Indigenous peoples, are free to exist like this, in a way we were always supposed to.

When I spoke with Luger, I felt every ounce of this future through the words we exchanged. As a young Native person, his art made me feel hopeful that this future could be attained, as it had already been imagined. As our conversation neared an end, the last words he said to me were, “There is a kinship, a relationship, and a culture shared in this space. It’s made to be whole in a way as a facet of something beautiful rather than the gem itself,” Luger said. “We’re just contributing cultural facets to something that sparkles in the sunlight, and I’m proud to contribute because we are all participants in creating the future.”

Correction: A previous version of this article referred to Carl Whitman as Cannupa Hanska Luger’s father. Whitman is Luger’s grandfather. The story has been revised to reflect this change.

Correction: A previous version of this article mistakenly credited an art piece to Ty Fierce Metteba that they did not participate in. The story has been revised to reflect this change.

Leave a Reply