They say a picture is worth a thousand words … but are all those words spelled right, grammatically correct, and actually making sense? You might want to check that. Today in the NSFP’s Copy Team’s exclusive series, we’re covering captions, alt text, and credits.

Salutations!

The copy team pretentiously greets the reader with a phrase from Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White, courtesy of Charlotte the spider herself. What you’ve just experienced, watchful reader, is a caption. This is a little ridiculous, writing a caption for a greeting instead of an image, but you get the point. Here at the New School Free Press, captions consist of alt text (required), credits (SUPER required), and a descriptive statement (encouraged) — the last being what usually comes to mind when you hear “caption.” These are used for all visuals, as well as social media posts.

Now, you must be thinking, captions, really? How can you get that wrong?

Well, let us tell you. You can get it VERY wrong.

While the Free Press has particular standards for captions, as every publication does, we’ll be outlining our specifics as well as what generally makes a good caption. And what is good? We’re glad you asked.

Descriptive. Concise. Accurate.

That’s what we mean by “good.”

The reader should be able to glean from a couple sentences (for a visual) or a couple paragraphs (for a post) what the caption is describing, why it’s relevant, and who was involved in the creation. A caption can be a viewer’s first impression of a work and possibly the deciding factor for whether or not they decide to read the work in full. So mistakes matter — even little ones.

Captions, as a whole, do the what, why, and who thing that was discussed above. Captions, as a part, provide a teaser of the larger story or pair with a visual to add meaning and clarity. Depending on the word count provided by social media platforms, some captions are longer than others. For Instagram, captions are 2,200 characters max, though NSFP sets Instagram guidelines at 150-250 words or three paragraphs. There’s no need to reveal your whole story in the caption. If you do, what is there left to read?

The key to social media captions is providing a blurb that piques the reader’s interest just enough, without giving away the part they really want to read (they should have to click on your story for this.)

A lede, or the opening of your story, is a good place to start. Ideally, it should hit all the Ws: who, what, when, where, and why. For example, in the NSFP Timothée Chalamet look-alike contest post, the lede was used for the Instagram caption.

On Sunday, Oct. 27, the park transformed into a mob scene filled with a swarm of press including Teen Vogue, Variety, and The Daily Mail — as well as hundreds of people gathered to watch the city’s first-ever Timothée Chalamet look-alike competition.

AND it piques interest.

Timothée Chalamet showed up to his own look-alike competition in Washington Square Park, but missed out on the $50 cash prize.

The caption does not reveal the winner nor the details of Timothée Chalamet’s appearance at the event — which, of course, is what people want to read about. And while most of the time we don’t like to gatekeep, this is gatekeeping done right.

A visuals caption, which is below images on the NSFP website, is a sentence (maybe two) that adds context to a visual or confirms details in/about the visual. It should be brief and necessary. If the image provides the context all on its own, a caption (as a part) may not be necessary.

What IS necessary are alt text and credits.

Alt text is a written description of a visual (photos, illustrations, graphics, etc.) for those who are unable to see it. So, the text is meant to provide a similar experience. Alt text should be descriptive but brief — focus on what needs to be conveyed. This may include the visual’s format, subject, color palette, setting, and any text. At the Free Press, we try to keep alt text to two sentences max. Longer alt text can be overwhelming and may make it difficult for screen readers to give someone a focused portrayal of a visual.

Instagram supports alt text up to 100 characters and X supports alt text up to 1,000 characters. Adding an image description in a social media caption may also be helpful. According to the Perkins School for the Blind, an image description goes directly in a social media caption (unlike alt text, which has its own box) and can be even more in-depth since it’s confined to the caption character count, instead of the alt text one. Currently, NSFP does not provide image descriptions.

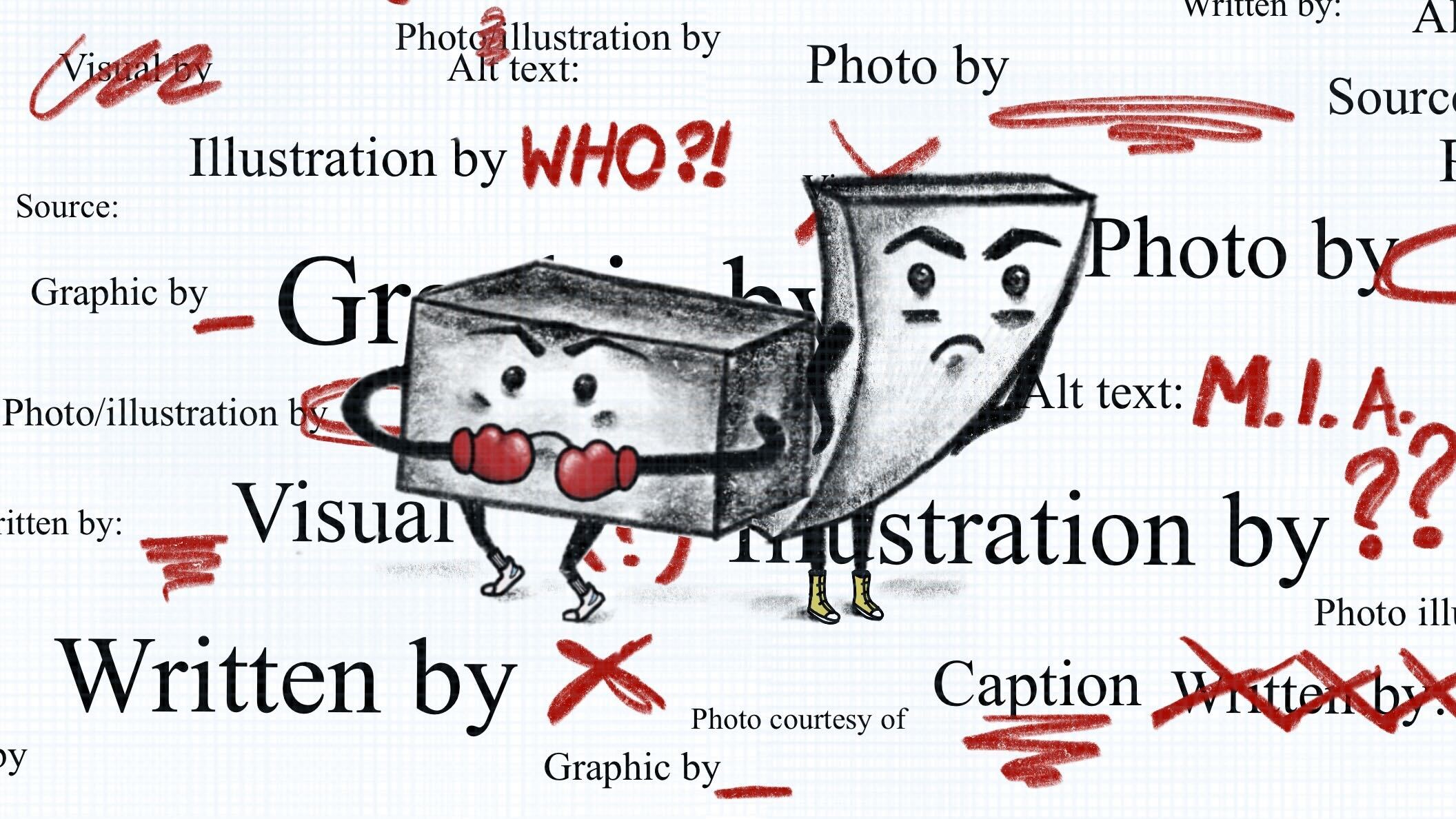

The alt text for the illustration by Emma Baxter associated with this article is as follows: Angry cartoon dash and comma surrounded by caption and visual credit verbiage, marked up with red pen.

Credits are perhaps the most important part of captions. Without credits, artists and writers will not get the recognition they deserve, hence the title, give credit where credit is due! Omitting credits can also be considered plagiarism.

At NSFP, visuals captions contain credits for the artist (e.g. Illustration by Emma Baxter). Writers’ names will appear in separate bylines. For social media captions, credits are for all contributors (writers/reporters, illustrators, designers, photographers, etc.).

It may sound easy, but you’d be surprised how many times people get credits wrong. Out of the three elements of a caption, credits often have major copy errors. The biggest and most common error is “Photo/illustration by …” This error is specific to our publication since in our story template, credits are written as such by default. Writers are then meant to specify the type of visual: photo, illustration, graphic, logo, photo illustration (see how there’s no slash?). Leaving it as “Photo/illustration” is sloppy and makes it look like we couldn’t take the time to review the credit.

Then there’s the nitty gritty that comes with credits.

If the visual is from an NSFP staff member, then you would proceed with the above form of accreditation (e.g. Illustration by Emma Baxter). If the visual is from someone outside of the NSFP and they have given you permission to use their work, then you would write “Illustration courtesy of …” If the work is from a different source or public domain, then they should be attributed as “Source:” There are additional rules for collaborations and credits do not have periods (as they are phrases) unless they are directly followed by a sentence for some reason (it happens).

These may seem like little things, but as someone has probably told you before, it’s all in the details. Think of captions as the smallest (but mightiest) representation of you and your publication. Just because it’s small, doesn’t mean it should be disregarded. Refinement makes certain writing, certain publications stand out. Take it from the NSFP Copy Team: give credit where credit is due, and put your best first impression forward.

Leave a Reply