After Years of Neglect, The New School Attempts to Recover its Institutional Memory

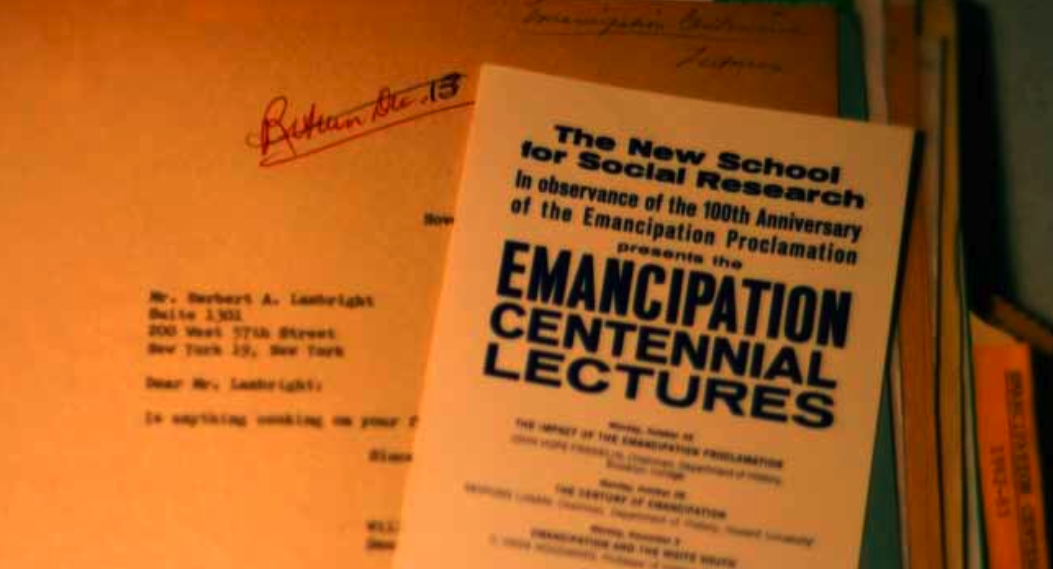

In 2011, while putting together a presentation on the politics of desegregation in New York City, New School for Social Research doctoral candidate Chris Crews stumbled across a promotional flyer that The New School distributed through its communications department.

“That sure as hell looks like Dr. King,” Crews recalled telling himself.

The press release contained a photo of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. standing at a podium, the distinctive arch of Tishman Auditorium behind him.

Crews contacted Fogelman Library archivist Carmen Hendershott. After doing some research, Hendershott found an old copy of The New School Bulletin indicating that Dr. King, among others civil rights notables, spoke at The New School in early 1964 as part of the “American Race Crisis Lecture Series.”

Over the weeks that followed, Crews teamed up with Hendershott and Lang professors Julia Foulkes and Mark Larrimore to find any evidence of Dr. King’s speech in the university library. In a trove of archival materials, they found boxes of reel to reel tapes — some labeled, some unmarked. After surveying the materials, they selected the tapes that could be most closely identified as documenting the lecture series.

Crews, a University Student Senate representative, secured money through the USS to digitize the tapes. Though the lecture series featured at least 15 speakers, only three and a half lectures were digitized. Only a portion of Dr. King’s address was recovered, but Crews believes that the rest of the tapes, and possibly more historical gems, may remain concealed.

“Who knows that we might find hidden in there besides Dr. King’s excerpts from his talk,” Crews said. “There might be other one-of-a-kind pieces of history there that we simply don’t know about, because no one ever thought it was important enough to put the time or the money into it.”

****

The recovery of the King tapes is just one instance in a larger pattern of how The New School treats its historical legacy. Since the university’s founding, its archival collections have been decentralized and, in turn, disorganized. Without proper areas to process and store them, and with no administrative backing to fund those operations, some of the The New School’s most valued collections have left the university. Papers belonging to University in Exile Scholars and to former Director Alvin Johnson are just some of the many collections that found their way to other institutions across the country, where they are now publicly available to the academic community.

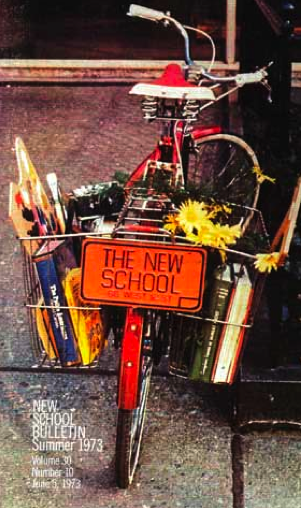

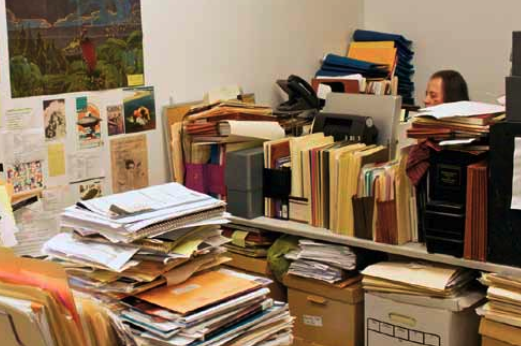

Due to a lack of funding and staff, The New School has never performed a comprehensive, or even preliminary, survey of its archival holdings. Archival materials — tapes, photos, papers, promotional materials and items in the press — have been loosely compiled by The New School’s library and departmental staff over the course of the university’s 90-year history. Many are now kept in boxes, closets and storage rooms in a variety of buildings across New York. Others have simply been thrown away.

In recent weeks, The New School’s librarians and archivists have moved to stop this course of deterioration, embarking on an effort to begin the laborious process of inventorying the university’s collections. While the project remains in its infancy, over the course of the next few years and possibly decades the library hopes to catalogue all of the The New School’s collections. With the requisite funding — as much as tens of millions of dollars — the inventory process would eventually allow the university to gain “intellectual control” of its holdings so that snapshots of history, like the 1964 Race Crisis Lecture Series, don’t remain hidden or, like the other tapes, disappear.

The first step for University Librarian Ed Scarcelle and his team: creating a basic inventory of The New School’s trove of historical documents and holdings. The ultimate goal would be a centralized archive worthy of the university’s historical legacy.

****

The New School currently houses three libraries: the Raymond Fogelman Social Science and Humanities Library, Mannes College’s Harry Scherman Music Library, and Parsons’ Gimbel Art and Design Library. In addition, Parsons is also home to the Kellen Design Archives, the university’s only official location dedicated to the processing and housing of archival materials.

Scarcelle, who is helping to lead the campaign for a centralized archive, said that the plan would bring these four collections together so that they are no longer seen as standalone institutions within the university.

“I think we’re trying to reflect what has been trying to happen over the past decade at the school,” he said. “Instead of thinking what’s best for me and my division, [we’re thinking] what’s best for The New School as an overall university.”

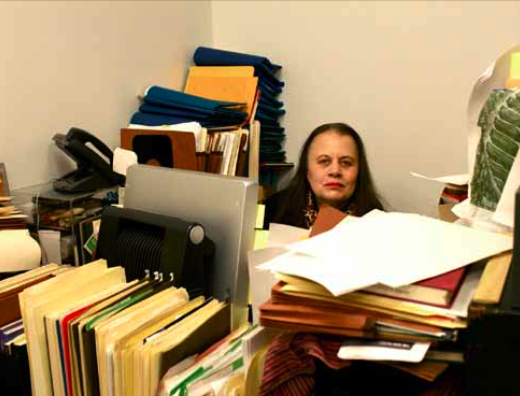

Blueprints for the future University Center’s library hang behind Scarcelle’s office desk on the ninth floor of Arnhold Hall, where he has been working as the university librarian since 2008. In his effort to preserve The New School’s archives, Scarcelle has been working closely with Wendy Scheir, director of Kellen Design Archives. Scheir, who has been with the university since 2008, described the The New School’s knowledge of its collections as “very general.” The first step, she said, is to prioritize collections by value and the danger of their well-being.

“It’s a really, really basic thing that needs to happen,” she said, “but it’s an important one.”

Some improvement was made in 2009 when the Fogelman Library moved out of the now-demolished building at 65 Fifth Ave. and archival materials were sent to a storage facility in Patterson, New York. Scheir estimated that the facility currently holds about 350 boxes of material, which are stored in a temperature-controlled environment.

“Moving off-site was a blessing,” said Scarcelle. “They’re much safer now.”

But many of the collections are in cardboard boxes, and may not be properly organized. At the Kellen Design Archives, Scheir displayed a box that had recently been retrieved from the Patterson location: photos and documents were stacked upright, causing the materials on either end to bend out of shape, potentially damaging them. A basic inventory would allow Scheir and her staff at Kellen to provide “rudimentary forms of protection,” such as placing materials in acid-free folders, in addition to cataloguing their contents.

In the long-term, Scarcelle and his team are looking at the financial realities. Because archiving materials is an expensive process that can cost an institution millions of dollars, they plan to assess the value of the university’s collections. This will, in turn, dictate whether the library should appeal to the administration for funding.

“A lot of the work that we want to do is to answer this question,” Scarcelle said. “Our goal is ‘seed work,’ so that in the not-so-distant future we have much stronger intellectual control and a much stronger proposal to the administration as to what can be done. We’re answering the question for the university.”

****

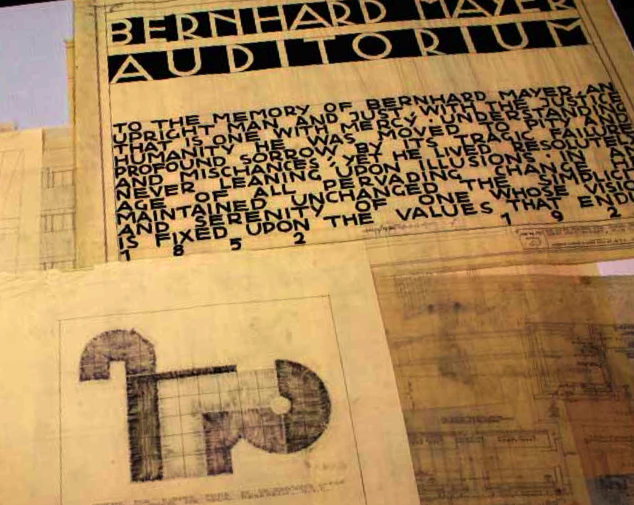

The New School, while a relatively young university, has an illustrious history. Founded in 1919, The New School for Social Research — the institution’s original name, before a series of rebrandings — was a revolutionary experiment in education. Some of its founders were defectors from Columbia University, where the administration had imposed an all-encompassing loyalty oath with the government. Others were simply eager to form a radical, modern and progressive institution that taught from the ground-up — one that did not represent the “ivory tower” so often used to describe higher education at that time.

The New School, while a relatively young university, has an illustrious history. Founded in 1919, The New School for Social Research — the institution’s original name, before a series of rebrandings — was a revolutionary experiment in education. Some of its founders were defectors from Columbia University, where the administration had imposed an all-encompassing loyalty oath with the government. Others were simply eager to form a radical, modern and progressive institution that taught from the ground-up — one that did not represent the “ivory tower” so often used to describe higher education at that time.

A series of radical programs differentiated The New School from other institutions in its early years. It offered the country’s first-ever adult education program, and was one of the first universities which had a predominantly female student body. It also housed what was arguably the first program dedicated to the study of race relations, with courses taught by W. E. B. Dubois, Thurgood Marshall and James Baldwin.

But The New School may be best known for its “University in Exile,” an initiative at NSSR that New School Director Alvin Johnson created to offer asylum to exiled European scholars. Between 1933 and 1945, The New School afforded refuge to 183 scholars, more than any other U.S. institution of higher education. Among them were Leo Strauss, Arnold Brandt, Max Werthheimer and Hans Simons.

Today, very few records from the University in Exile remain in The New School’s possession.

Many of them moved to SUNY Albany in the 1980s when John Spallek, a faculty member in the German Department there, embarked on a survey of German emigre scholars who had fled to the U.S. during the 1930s. One of the universities that Spallek visited to look for records was The New School. According to Geoff Williams, an archivist at SUNY Albany, Spallek discovered an enormous amount of material at The New School, including records from the Emergency Rescue Committee. Formed to help Europeans flee the Nazis during World War II, the committee had a close working relationship with The New School.

The Spallek collection now holds hundreds of German Jewish emigre files and is SUNY Albany’s largest archival collection, consuming more than 750 cubic feet of space.

“The main reason why the collection was not built at The New School was because The New School had no archives,” said Williams. “If we didn’t do it, no one was going to.”

Carmen Hendershott, who was hired as Fogelman Library’s reference librarian in 1970, and has worked at The New School ever since, believes that the loss of the University in Exile papers is indicative of the university’s lack of concern for its history. The records were donated to SUNY Albany, Hendershott said, because the university librarian at the time felt that they weren’t safe at The New School.

“[At SUNY Albany] they are protected and accessible, and there are finding aids, and they are in a secure, humidity- and temperature-controlled environment, which our institution simply doesn’t provide,” said Hendershott. “As far as I know, they have never tried to provide it.”

But when The New School decided to give away the University in Exile Papers, there was no assurance that they would be made available to the public, said Scarcelle, and no assurance that they would be stored safely.

“They probably made the best decision they could at the time,” he said. “[The collection] is safe and it’s public. But there was no guarantee of that.”

****

Archival collections are essential to the culture of a university — particularly a university that champions its history as avidly as The New School.

“All schools — and especially The New School, founded on the concepts of education embedded in activist culture — are part of the cultural capital of the country,” said David Smith, a reference librarian at the New York Public Library for 31 years until his recent retirement. “It’s surprising to learn that The New School has never had an archivist and has never organized its own archives,” Smith added.

A centralized archive, librarians and archivists say, would make it easier for scholars and authors to research The New School — another factor that is motivating the school’s librarians to push for change. Academics who are working on

dissertations or histories on The New School have had to look elsewhere.

The lack of an archival collection, according to Hendershott, has stunted research at the university. Over the years at Fogelman Library, she has become a magnet for institutional knowledge and is the go-to figure for questions regarding the institution’s past.

Before Fogelman Library moved to 55 W. 13th St., Hendershott remembers boxes of archival materials stacked in the humid basement of 65 Fifth Ave. When space was tight, materials were sometimes thrown out, or put in less than desirable locations. She recalled one occasion when Peter Rutkoff was conducting research for his book, “New School: The New School for Social Research.” Rutkoff found a set of boxes in the basement boiler room; inside the boxes were papers pertaining to the Institute of World Affairs, an economics program established at The New School in 1942.

“These are not the kinds of things that an institution does when it cares about its history,” said Hendershott. “That isn’t where you keep something if you value it and want to make sure it’s protected.”

Rutkoff also remembered the disorganization. When he came to research his book in the 1980s, he found materials scattered about the building’s basement.

“I just rummaged around,” he told the Free Press. “There was no order, and more importantly, there was no protocol about what to save and what not to save.”

Rutkoff remembers one discovery in particular: the briefcase of a New School faculty member. When Rutkoff returned it, the faculty member was shocked; he hadn’t seen the briefcase in 25 years.

More than two decades later, the state of the university’s archives has hardly changed.

“Given the fact the The New School was started by two historians,” said Rutkoff, referring to Charles Beard and James Harvey Robinson, “it would be nice if it would recover some of its history.”

For Hendershott, experiences like Rutkoff’s, the loss of the University in Exile papers, and the

departure of Alvin Johnson’s papers for Yale University in 1967 are all part of a larger problem: a lack of support from the university’s administration. And while she believes that the creation of a basic inventory is possible, administrative support, in her opinion, will be crucial to save the legacy of the university.

“I do not know where this support will come from,” Hendershott said, “because the administration has never shown any particular interest in supporting the archives of The New School, and they have never shown any initiative in trying to build it or develop it.”

University President David Van Zandt acknowledged that past administrations have not paid particular attention to archives.

“For generations this university was run by people individually and sometimes they didn’t find it important,” said Van Zandt.

The office of the president even houses a separate archive, the contents of which are not shared with the university community through public finding aids or Fogelman Library. Jennifer Orellana, who as administrative assistant to the president is tasked with maintaining the archive, told the Free Press that she wasn’t familiar with its holdings.

“I haven’t had too many requests so far,” Orellana said. “There’s a lot of confidential stuff in relation to the board of trustees’ information.”

In a later email to the Free Press, Orellana indicated that she had found materials in the collection that “might fit the description of history or culture of the university” and was looking into the confidentiality of those materials. As of press tim

e, though, Orellana would not comment on the materials or the scope and size of the collection.

Phoebe Berg, who oversaw the presidential archive for four years before moving to the office of the general counsel, confirmed that its holdings are confidential.

Van Zandt, however, was unaware that his office held an archive.

“I don’t know of one,” he told the Free Press. “When I took over, there were records of the board of trustees meetings. That was something that was being kept in the secretary’s office. As far as documents — I’m not even aware of one, in part I think because it doesn’t exist.”

“We’re one unit here and we work as team, and the idea of having a presidential archive strikes me as odd,” he added. “I’d love to see it if someone finds it!”

****

Once the university has catalogued its own collections — a process that could take years — Scarcelle, the university librarian, hopes that other materials around the school will also be processed. Each of The New School’s various buildings holds an array of files and documents which could be of value.

Consider, for example, the small room tucked away on the third floor stairwell at The New School’s 66 W. 12th St building. The room is known among staffers in the know of its existence as “the rat room.” Cabinets flank the cramped walls while boxes, heaving in the weight of their contents, rest on the concrete floor.

“There are no rats in the room,” said Nicholas Allanach, who has worked in the executive dean’s office at The New School for Public Engagement for five years. “It’s a place where we store our files over the years.”

The dusty and vaguely-labeled files hold pieces of New School history: papers related to an African Studies program in the early 1960s; calendars for film screenings in the 1970s; catalogues of art exhibits before the university’s acquisition of Parsons; files from the Lee Strasburg Institute, which was born out of the Actors Studio at The New School; old student applications to the Graduate Faculty; and boxes of light-stained copies of The New School Observer, once the university’s newsletter.

For the dean’s office, though, the only useful files in the rat room are faculty contracts, most from the 1990s. The rest are stored away with no specific purpose in mind, vulnerable to destruction.

At The New School for Social Research, formerly the Graduate Faculty, a separate and considerably larger batch of archival materials also exists. Shayne Trottman, executive assistant to the dean at NSSR, first recognized the amount of archival material a year ago when she arrived at The New School.

“This summer I plan to try and get them into some kind of shape,” she said. “We have lots of documents hanging around in different places.”

The Graduate Faculty also stores materials off-site, separate from the university’s collections, which the library has never evaluated. Over the years, inventories of the materials — if inventories ever did exist — have gone missing.

“Whoever did the storage didn’t keep up records of what they were storing,” said Trottman. “Or when they left, the knowledge went with them.”

New School for Social Research Dean Michael Schober acknowledged that his office has “not been in a time or space yet where we can really work on that.” However, Schober was very optimistic that conversations about inventorying archives are ongoing at the university.

The case of the rat room and the Graduate Faculty archive are not uncommon on campus. In the end, though, the preservation of these various, unofficial collections simply comes down to funding.

“Oh, absolutely,” said Scarcelle when asked if the university library would like these additional collections. “It’s simply a resource issue.”

****

For Scarcelle and his team, the immediate concern is the stability of the library’s current archival materials. A basic inventory will allow them to provide elementary levels of protection for vulnerable materials and, they hope, create online summaries of documents that would be available to the public through Kellen’s website.

For Scarcelle and his team, the immediate concern is the stability of the library’s current archival materials. A basic inventory will allow them to provide elementary levels of protection for vulnerable materials and, they hope, create online summaries of documents that would be available to the public through Kellen’s website.

But the most critical issue is funding. Scheir and her staff at Kellen are slowly making their way through the off-site collections, box by box. A full inventory, though, might take decades.

“It’s very, very hard for the staff that we have now to take on the task we’ve taken on,” said Scheir.

The library staff and administration recognize that given The New School’s financial constraints, a survey of materials — and the creation of an archive — is not a top priority.

“We’re in a very difficult position because we have such limited resources,” said Van Zandt. “I’d prefer to put them towards student and academics; we’re always making trade-offs.”

Scheir remains undeterred. She has applied for the for a grant through The Council on Library and Information Resources’ Hidden Collections Program, designed to aid institutions, like The New School, which have large amounts of unprocessed materials. In the event that Kellen is awarded the grant, it would allow the hiring of four new staff members over a two-year period to add to the archive’s current staff of three. After that period of time, the university library will be able to look forward and decide how to continue the process of creating a centralized archive.

“Our desire is there, and we’re working as hard as we can,” Scarcelle said. “I’d be curious to see where we are in six months to a year.”

The dream, at least for Hendershott, would be for the university to construct a proper archive with humidity and light control, adequate storage space, and separate locations for the processing and viewing of materials. The cost for such a facility would be enormous, but Hendershott feels that, in the case of The New School, it can’t wait.

“The need for keeping your history is not as obvious,” she said. “You don’t see it with the same urgency.”

with reporting by Brianna Lyle, Henry Miller, and Christopher Hooks

Leave a Reply